Ruins of a Late Roman desert fortress, that was converted to a Byzantine monastery.

* Site of the month Mar 2018 *

Home > Sites > Judea> Allon Road > Kilya (Rimonim)

Contents:

* Fortress

* Lookout

Background:

Khirbet Kilya (also: Kilia) is a ruin of a Roman fortress, which was later converted to a Byzantine monastery. It is adjacent to the modern Rimonim community in the Judea desert.

The 20 Dunam complex includes 2 interconnected square structures, dated to the 4-5th century AD (Late Roman) on the north side, and a 6th century AD (Byzantine monastery) extension on the south side.

Location:

The community of Rimmonim is located along the Allon road (highway #458), above the Judean desert east of Jericho.

The ruins of Kh. Kilya, in the south east side of the community, are at an altitude of 656m above sea level. The deep valley on its north side (Wadi el-Wahitah), which flows down to the Jordan valley, is 150m below the ruins – a steep descent.

History:

-

Biblical period

A Biblical map is below, with a red marker indicating the location of the site, is shown here. The map provides some suggestions to the Biblical places, but not all of them are fully identified. The site overlooks the mountains above the Jordan valley, north of Jericho, an area is marked as the “valley of Achor”.

Area around the site (red dot in the center) – from Canaanite to the Persian period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

-

Valley of Achor

The Judean desert stretches to the east of the place, descending to the Jordan rift north of Jericho. According to Biblical scholars, this area is the Biblical valley of Achor.

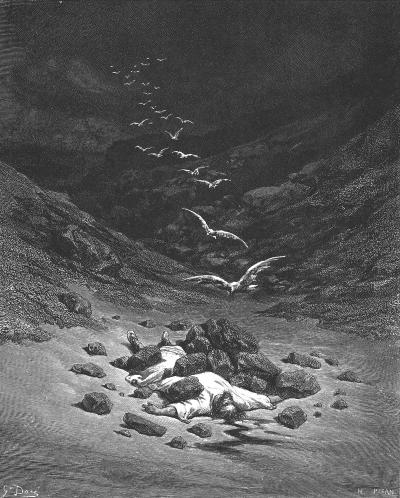

The valley of Achor is mentioned in relation to the aftermath of the the fall of Jericho. Achan son of Zerah stole loot from Jericho, against God’s commandment. God’s anger led to the loss of the first attack on Ai, the next city that the Israelites attacked. Achan was punished by stoning in order to gain victory over Ai. The place of stoning was then named the valley of Achor (Hebrew for “trouble”).

(Joshua 7:24-26): And Joshua, and all Israel with him, took Achan the son of Zerah, and the silver, and the garment, and the wedge of gold, and his sons, and his daughters, and his oxen, and his asses, and his sheep, and his tent, and all that he had: and they brought them unto the valley of Achor.

And Joshua said, Why hast thou troubled us? the LORD shall trouble thee this day. And all Israel stoned him with stones, and burned them with fire, after they had stoned them with stones.

And they raised over him a great heap of stones unto this day. So the LORD turned from the fierceness of his anger. Wherefore the name of that place was called, The valley of Achor, unto this day”.

Stoning of Ahan- Drawing by Gustav Dore (French artist, 1832-1883)

One of the early Biblical scholars who identified the place to the north of Jericho was Eusebius Pamphili (better known as Eusebius of Caesarea). A 4th Century Greek historian of the Church, Eusebius wrote in his book “Onomasticon” about the valley:

“The valley called Achor [in Hebrew emecachor which means valley of confusion or violence because of the confusion or violence in Israel] where they stoned Achor (Achan), who stole what was under ban from whom Achor is named. It lies north of Jericho and is even now the name by those nearby”.

In 1877 the area north of Jericho was a candidate for an agriculture village drafted by Joel Moshe Salomon. He named the project as “Petah Tikva” (Hebrew for “door of hope”), inspired by Hosea’s prophecy to turn the valley of Achor into a fertile place (Hosea 2:15): And I will give her her vineyards from thence, and the valley of Achor for a door of hope” . The land was purchased, but the project was nullified by the Sultan as too many foreigners were behind the project. Salomon moved it to a place east of Jaffa and decided to retain the name. The agriculture settlement that grew into the large modern city of Petah Tikva.

-

Late Roman period (4th-5th century AD)

A fortress was constructed in Kh. Kilya at the end of the 4th century or beginning of the 5th century. Its primary purpose was to protect the road from the hill country to the Jordan valley, in a sector facing Jericho.

The square 2-level structure measured 20.7m long and its walls were 1.3m thick. Together with another Roman tower across the Wady el-Wahitah valley (named “el Qasr”), these fortifications defended the eastern front at this section, and also provided a view of the Roman road above Wady Taiyibeh connecting the mountain area down to Jericho.

Y. Magen, who excavated the site, observed (“Late Roman fortresses and towers”, pp. 206-207) that the late Roman fortresses in Samaria and Judea had common features. They were located on hilltops and above riverbeds, in commanding position of Roman roads but not adjacent to them. They were not found near towns, nor near agriculture land. They were built of high quality materials and workmanship. These fortresses were not built in purpose of handling siege, so their plan lacked protruding towers. Their primary function was a security base – hosting soldiers who patrolled the frontier, and guarded the main roads.

-

Byzantine period (6th-7th century AD)

At the end of the 5th century the fortress was abandoned, and was then rebuilt and converted to a monastery. This transition of the structure shares the fate of other Roman fortresses in Samaria and Judea (for example, Kh. Deir Sam’an and Kh. Deir Qal’a). During the conversion the structure was made fit to serve the new residents, by adding a chapel, agriculture installations, and additional rooms.

The surge of the Christian monks in the Judean desert during the Byzantine period created a thorough change in the number of settlements located in this harsh desert landscape. About 60 (!) monasteries were established during this period in the desert, and between 10,000 to 30,000 monks were living there.

The monastery in Kh. Kilya was founded in the 6th century, after the Roman fortress was converted to a ‘coenobium’ type monastery. The Coenobium (pronounced Coi-Noi-Bee-Yum) was a communal monastery, where a number of structures were surrounded by a wall and the monks lived there in a commune. The monks lodged inside the compound and followed a strict daily schedule.

This word is based on the Greek words Koinos (common) and Bios (Life). The emphasis of this form is the community life, in contrast with the solitary living of the hermits which was too lonely and often led to mental breakdown. It was larger, more disciplined than the Laura (another type of monastery), and followed a daily schedule. For many hermits, it was the first station before wandering to the desert or joining a Laura.

The monastery was deserted during the Early Muslim period (638-1099).

-

Ottoman period – PEF survey (19th century AD)

The area around the site was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. The site was reported in Sheet 15 (Volume 2 p. 395) merely as “a modern ruined house”, as they failed to identify the antiquity of the site.

A section of their map is seen here. The ruined Kilia is situated above the deep gorge of Wady Dar el Jerir (Arabic for: valley of the house of el Jerir; name of a great Arabic poet). Across this valley is a site named el Kusr (Arabic for “the castle”) – the ruins of a Byzantine monastery.

Part of Map Sheet 15 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

A Roman road is located 2km to the south on the south side of Wady et Taiyibeh (Arabic: the goodly valley, named after the Arab village 3km to the west). This desert path later became known as “Tariq abu George” – a road connecting the Ramallah and Jerusalem to Jericho, which was paved by the Jordanian Army in 1948, named after one of their Irish engineers. The road is still in use.

-

Modern period

In 1967 the area was conquered from the Jordanians by the Israeli army. In 1977 a Nahal settlement was founded near the ruins. Nahal is a paramilitary Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) program that combines the military service with agriculture activity, and has established dozens of bases that were eventually turned into civilian communities.

In 1980 a civilian community was established in the premises of the Nahal settlement, settled by the first 25 families. The community was named after the rock of Rimmon (Hebrew for: Pomegranate), where the men of Benjamin took refuge. This event took place when the tribesmen of Israel rose against the Benjamites who refused to deliver up the men of Gibeah after they abused of a Levite’s concubine while lodging in Gibeah (Judges 20 47): “But six hundred men turned and fled to the wilderness unto the rock Rimmon, and abode in the rock Rimmon four months”. About 4km to the west is the Arab village of Rummon, which may have preserved the ancient name of Rimmon.

An archaeological excavation was conducted in the site by a team headed by Y. Magen, the staff officer of Archaeology in Judea and Samaria. Their findings are the source of information on the site.

Photos:

(a) Aerial Views

Ruins of a Roman fortress, converted to a Byzantine monastery, are located in the Rimonim community in Samaria.

The 20 Dunam complex of Kh. Kilya includes 2 interconnected square structures, dated to the 4-5th century AD (Late Roman, on the north side) and 6th century AD (Byzantine monastery, on the south side).

This aerial view is from the north side of the ruins. On the east (left) side of the ruins is the deep gorge of Wady Dar el-Jerir (also Wahitah) – 150m below the ruins.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The next aerial view is from the south side:

A closer look on the ruins is next. The area covers approximately 20 dunams in size.

(b) Entrance to the monastery

The following sections are arranged from south to north.

The entrance to the complex of the fortified Byzantine monastery was on the south side, as indicated by a yellow square on the illustration.

The photo below shows the entrance to the outer courtyard from the southern side.

(c) Outer courtyard

A large paved courtyard was located beyond the entrance to the monastery complex. Around it are a number of rooms. This was part of the coenobium-type monastery, where the monks resided in the rooms and were part of a monastic community.

The courtyard and rooms were added in the second phase of construction, during the 6th century, when the Roman fortress was converted from a military post to a community of desert monks.

Another view, from the north side of the courtyard:

(d) Monastery rooms

Around the large courtyard are a number of rooms – the residence of the monks.

Rooms on the east side:

Rooms on the west side:

(e) The Fortress

The northern section of the Byzantine monastery started as a Late Roman period fortress. It was built around the end of forth century or beginning of the fifth century AD. This was one of the Roman military outposts that guarded the frontier.

The fortress is square, 20.70m long, and surrounded by a 1.3m thick wall built of large, well made ashlars (finely dressed stones). Their external side has marginal drafting and prominent or flat bosses. The inner side was coated with a wide white plaster layer.

The plan of the fortress is a central courtyard surrounded by 8 rooms – 3 on the west, 3 on the east, 2 on the north side. A large water cistern is located in the center of the courtyard.

This aerial view was captured from the north side.

The fortress was two or three stories high. Only the north west room, seen here from its outer side, survived to a higher level.

Entrance to the Fortress:

The entrance to the fortress was in the center of the south wall. It is marked here with a yellow square.

The entrance was was equipped with a rolling stone, that sealed the entrance during trouble times. The rolling stone was added during the second phase of building, when the fortress was converted to a monastery in the 6th century.

The use of rolling stones is common in other desert monasteries and fortresses, as it added more security to the remote posts. The remote monasteries were a target of attacks by Saracens, and extra protection was required.

Another view of the entrance, from the inner side, is seen in the next photo. Notice the large stone slabs that were used for the pavement of the inner courtyard.

(f) Inside the south western room of the fortress

The only standing room is located on the south western side of the fortress (marked by a yellow square).

The door into the room was on the corner of the wall. A massive lintel stood above the entrance.

The following photo is the inner side of the entrance. Ethan, almost 2m tall, examines the arch that supported the inner wall.

Another view of the inner side is below. Beams were inserted into holes along the top side of the walls. They were used to support the ceilings which were made of wooden planks.

(g) Inner courtyard of the fortress

In the center of the fortress was a courtyard, which was surrounded by rooms. It is indicated by a yellow square on the illustration.

On the east side of the courtyard, seen here in this photo, was a portico. A staircase (seen in the center) led up to the second floor, where a chapel was built during the second building phase (6th century). The pillars in the center of the courtyard were the bases of massive arches that supported the second level and the chapel.

One of the elements in the courtyard is the base of a column.

(h) North eastern room

The north east room is indicated by a yellow square on the illustration.

Above this room was a chapel which was added in the 6th century. It was supported by massive arches that were added in the courtyard and in the rooms.

The following photo shows the north eastern room, as seen from the northern room. The entrances to the rooms were on the corners, as can be seen here where Ethan is standing (endlessly talking to his cell phone…).

The floor on the rooms were paved with white mosaic stones.

Doorposts were fitted with bolt sockets. One of these sockets is seen on the door post here on the left side.

(i) Northern room

The location of the northern room of the fortress is indicated on the illustration as a yellow square.

The northern room was rebuilt in the 6th century, during the second phase of the construction when the fortress was converted to a monastery.

The floor was paved with white mosaics.

Burial troughs and a cist tomb were cut into the floor. They served as a crypt.

A fragment of a stone with a cross lies on the floor.

(j) Eastern room

The south side of the eastern room is shown here.

(j) Western rooms

The location of the north western corner room is indicated here as a yellow square.

The photo below shows a view of the corner room as seen from the adjacent room.

A closer view:

Another stone carved with a cross was unearthed here.

(k) Eli’s lookout

A memorial observation balcony is located on the east side of the community, dedicated to Eli Asayag. Eli, one of the founders of the community, died in 2002 from a bite of a rare poisonous snake (Atractaspis engaddensis).

From the observation platform are great views of the desert area, facing Jericho, the Jordan rift valley, and the mountains of Moab beyond it. Notice the road that crosses the mountains below. This is “Tariq abu George” – a road connecting the Ramallah and Jerusalem to Jericho, which was paved by the Jordanian Army in 1948. It followed the track of the Roman road. This commanding position of the road, and the region around it, is why this location was selected for the fortress.

An engraved metal plate shows a panoramic map of the sites around the area.

Pressing the buttons on the plate is a taped message describing the history of the area in Hebrew and English. You can listen to description. Click here to run it.

(l) Western area

To the west of Rimmonim is the Allon road (highway #458), crossing from north to south along the eastern side of the hills. An open area between the community and the road is used for grazing.

(m) Video

![]() Fly over the site with this YouTube video.

Fly over the site with this YouTube video.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

Rimmonim – Hebrew: Pomegrantes. The community is named after the rock of Rimmon (Pomegranate) where the men of Benjamin took refuge (Judges 20 47): “But six hundred men turned and fled to the wilderness unto the rock Rimmon, and abode in the rock Rimmon four months”.

Kilya, Kilia – PEF dictionary suggested: “hilly ground”.

Links and references:

* External links:

- Rimmonim – community home page (Hebrew)

- Judea and Samaria Researches and Discoveries – Y. Magen 2008 (kh. Kilya, pp. 178-183)

* Biblewalks sites:

- Byzantine monks – info on desert monastic life

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- BibleWalks Youtube channel

- Allon road – sites along the eastern side of Judea and Samaria

BibleWalks.com – dreaming in the Bible Lands

Michmash<<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next Judea site—>>> Kh. Jumjum

This page was last updated on Aug 26, 2017

Sponsored Links: