Bronze and Iron age findings in the area between Ma’ale Michmash and Michmas.

* Site of the Month Dec 2017 *

Home > Sites > Judea> Allon Road > Michmash, Ma’ale Michmash

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Ma’ale Michmash

* Iron age fortress

* Tower hill

* Shaft tombs

* More tombs

* Cistern

Biblical

Etymology

Links

Background:

In the area around the Jewish community of Ma’ale Michmash, and the Arab village of Michmas, are several ancient sites dated to the Bronze and Iron age. A great battle between the Philistines and the Israelites was fought in the fields of Michmash during the reign of King Saul.

1 Samuel 13:5: “And the Philistines gathered themselves together to fight with Israel… and they came up, and pitched in Michmash“.

Location:

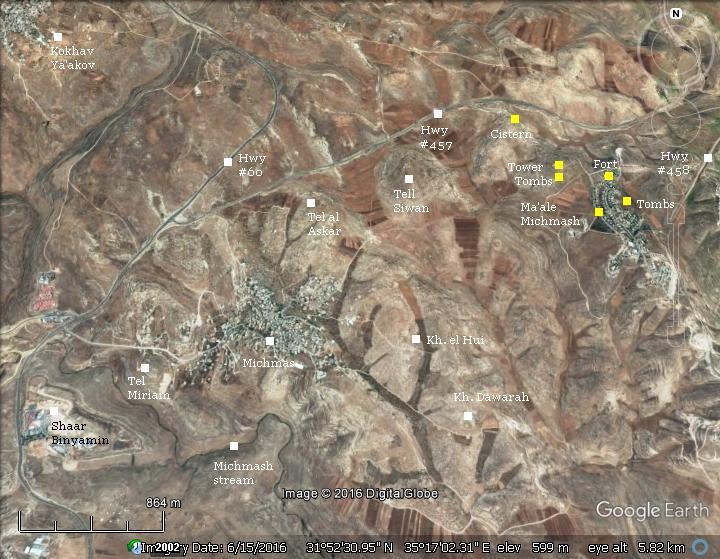

This map shows the area of Michmash, 11km north east of the old city of Jerusalem. In the lower part is the valley of the Michmash stream (Wady es Suweinit) which later joins to Nahal Prat (Wady Qelt). Two communities are located north of the Michmash stream: the Arab village of Michmas and the Jewish community of Ma’ale Michmash.

History:

-

Prehistoric periods – Intermediate Bronze age (2,400-2,000 BC)

A large number of Intermediate Bronze age burial shafts were found on the western and eastern side of Ma’ale Michmash.

-

Iron Age (1200-586 BC)

A great battle between Philistines and the Israelite army, headed by King Saul, occurred in ~1050 BC near Michmash. (1 Samuel 13:5):

“And the Philistines gathered themselves together to fight with Israel, thirty thousand chariots, and six thousand horsemen, and people as the sand which is on the sea shore in multitude: and they came up, and pitched in Michmash, eastward from Bethaven…”. The battle is also detailed in Josephus’s Antiquities 6:6.

The Israelites won the battle although they were greatly outnumbered and inferior in arms. This battle is one of the most detailed in the Bible, covering two chapters. It also provides a description of the area: Michmash is located east of Beth-Aven and Bethel (13:5), and located near a strategic narrow passage (13:23).

A Biblical map is below, with a red marker indicating the location of the site, is shown here. The map provides some suggestions to the Biblical places, but not all of them are fully identified.

The map shows that strategic roads passed through Michmash, connecting the mountain area of Judea down to Jericho. In modern excavations the archaeologists identified an Israeli fort in Khirbet Dawarah south east of Michmash along the road to Jericho (Finkelstein, 1988), and traces of an Israelite period road from Geba to Michmash along 1.5km (Yoel Elizur, 1985).

Map of the area around the site (red dot in the center) – from the Canaanite to the Persian period (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

-

Assyrian conquest (701 -630 BC)

The Assyrian empire conquered the North Kingdom of Israel in 732 BC, destroying most of the cities and villages in the land. The South Kingdom of Judah managed to survive this onslaught by teaming up with the Assyrians, but not for long. After the death of the Assyrian King Sargon II (722 - 705BC), King Hezekiah son of Ahaz (reigned 715-686 BC) mutinied against the Assyrians. He joined other states in the area who attempted to free themselves from the Assyrian conquest.

Anticipating the coming Assyrian intrusion, Hezekiah fortified Jerusalem and the major cities.

The Assyrian army came in 701, led by Sennacherib, son of Sargon II (2 Chronicles 32 1): “After these things, and the establishment thereof, Sennacherib king of Assyria came, and entered into Judah, and encamped against the fenced cities, and thought to win them for himself”. According to Isaiah, the Assyrians entered through the east to Judea, camped near Michmash (Isaiah 10:28):

“He is come to Aiath, he is passed to Migron; at Michmash he hath laid up his carriages:”.

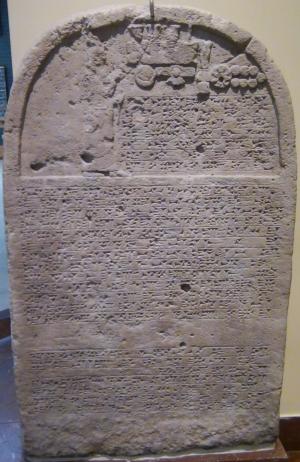

According to an Assyrian stele found in the ruins of the royal palace of Nineveh, Sennacherib conquered 46 cities in Judea. Jerusalem was spared from destruction, and the Assyrians retreated. Jerusalem continued to pay heavy taxes to the Assyrian conquerors, but fell 114 years later to the Babylonians.

Sennacherib’s stele with relief and inscription; Nineveh;

limestone [Istanbul Archaeological Museum]

A late Iron Age fortress was excavated on the north side of Ma’ale Michmash. The excavator of the Ma’ale Michmash fortress suggests that the fortress was constructed at the end of the 7th century, probably during the reign of Josiah (641-609 BC) who expanded the Judean Kingdom following the Assyrian pull back from the Levant (at ~630).

The square fortress (8.5m x 9.0m) walls are made of 0.8m wide hewn stones, with a plan type of a three-room house.

According to the excavator S. Riklin, the fortress commanded 2 east-west roads, one of them (to Jericho) was described in 1 Samuel 13:18: “…the way of the border that looketh to the valley of Zeboim toward the wilderness”. A twin fortress was found in Khirbet Shilhin, 5 km south east, located on the side of the southern road from Michmash to Jericho. Both fortresses were the central defenses on the north east border of the Judean Kingdom at the end of the Iron Age.

-

Babylonian period (587-539 BC)

The Babylonian empire rose after the fall of the Assyrians (610 BC), defeated the Egyptians (609 BC) and conquered the land until the Nile (2 Kings 24 7): “… for the king of Babylon had taken from the river of Egypt unto the river Euphrates all that pertained to the king of Egypt”.

After two attempts of the Judean kings Jehoiakim and Zedekiah to disengage from the Babylonian conquest, Nebuchadnezzar II destroyed the Judah kingdom completely in 587 BC. In this intrusion (587) most of the cities were leveled, including the fortress in Ma’ale Michmash.

“Lions in Relief” – from the procession street in Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar II period (604-562BC); glazed brick

[Istanbul Archaeological Museum]

-

Persian period (539-332 BC)

In 539 BC the Persians defeated the Babylonians, and allowed the exiles to return to Zion (538 through 445 BC). It then was rebuilt by the returnees, lead by Zerubbabel, during the Persian period (Ezra 2:1-2, 27 and also Nehemiah 11: 6-7, 31):

“Now these are the children of the province that went up out of the captivity, of those which had been carried away, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away unto Babylon, and came again unto Jerusalem and Judah, every one unto his city; Which came with Zerubbabel: Jeshua, Nehemiah, Seraiah, Reelaiah, Mordecai, Bilshan, Mizpar, Bigvai, Rehum, Baanah. The number of the men of the people of Israel…. The men of Michmas, an hundred twenty and two.”. The newly built Michmash was probably located in the area of the Arab village of Michmas.

-

Ottoman period – PEF survey and excavations (19th century AD)

The area around the site was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener.

A review of several sites is listed in Volume 3 Sheet XVII, including (p.12):

“Mikhmas – A small stone village on the slope of a ridge. The houses are poor and scattered. The water supply is from cisterns. It has a well to the east, and some scattered figs to the west. On the north are rock-cut tombs ; an ancient road leads past the place. There are foundations and remains of former buildings in the village ; on the south a steep slope leads clown to the great valley, Wady Suweinit. This place is the ancient Michmash, which is placed by the ‘Onomasticon’ (s.v. Machmas) 9 Roman miles from Jerusalem. The distance is 71 English or 8 Roman miles in a line.”

On page 149 is a review of the archaeological findings :

- “Mikhmas – In the village are remains of old masonry, apparently a church. A pillar-shaft is built into a wall in the north-west corner of the village. Two lintel stones are built over the door of another house, one with three crosses in circles, the second with a design apparently cut in half”.

A section of their survey map:

Part of Map Sheet 17 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

On page 11 and 113 are reviews of other ancient sites around Michmash that are listed on their map:

- “Khirbet el Haiyeh – Heaps of stones, ruined walls, a ruined building, and a cistern. The place stands on a Tell, and appears once to have been a village”.

- ” Kh. Dawarah – Traces of ruins”.

- “Kh. ed Duweir-Foundations and a Mukam”.

Photos:

(a) Ma’ale Michmash

Ma’ale Michmash (Hebrew for “Michmash Ascent”) is a communal settlement (established 1981) in Benjamin region, north east of Jerusalem, situated along the southern section of the Allon road (Hwy #458), near the Biblical city of Michmash.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

A road from east (Jericho) to west (Judea) passes on the south side of the community. It may have been the road described in 1 Samuel 13:18: “…the way of the border that looketh to the valley of Zeboim toward the wilderness”.

(b) Iron Age Fortress

A late Iron Age fortress was excavated on the north side of Ma’ale Michmash. Its remains are located near one of the synagogues of the community, on the top of a hill at 610m above sea level.

The fortress was discovered by Itzhak Sapir of Ma’ale Michmash, and excavated by S. Riklin with the assistance of the Staff officer of Archeology within the Civil Administration of Judea and Samaria. It appears on the Benjamin Survey as site #248 (Magen and Finkelstein, 1993).

The remains are located in an open public area, on the northern side of the synagogue.

This square structure (8.5m x 9.0m) was built at the end of the 7th century BC, and was destroyed during the babylonian conquest. Its walls are made of 0.8m wide hewn stones, with a plan type of a three-room house.

Entrance to the structure was from the north side via a 1m wide door. Near the entrance is a staircase, which could have led to the second level of the structure. The steps could also have been part of a ritual altar (“bamah”), as found in other fortress in Iron Age Judea (Horvat ‘Uza and Horvat Radum).

The ground view below shows the north western side of the structure. The western room is 2.50m wide, which is the same as the central room, but larger than the eastern space (2.0m wide). A line of three monolith columns, 1m high, separate the western and eastern rooms. In the space between the columns are smaller stones.

The following photo is a view from the south western corner. On this corner is a semicircular wall (marked as “W-43”) which may have been a silo. Inside the excavations revealed a dipper juglet and a perfume juglet.

The next view shows the south eastern corner of the structure.

The ceramic vessels found in the structure were dated to the end of the Iron Age. Its homogeneous composition implies that the fortress was used within a short period, and used until the destruction of the Judean Kingdom.

The eastern side of the structure is below. In the very far background is Jerusalem, while on the hill on the right is the observation tower hill.

On the northern side of the fortress are other traces of the ancient site, which include: cattle fences, rock surfaces with cup marks, three caves and a cistern.

A cistern is located near the road. The cistern stored water for the soldiers who stationed the fortress.

A broken cover stone for the cistern is seen in the following photo.

![]() Fly over the Iron Age fortress with this YouTube video:

Fly over the Iron Age fortress with this YouTube video:

(c) Tower hill

To the west of the fortress is a hill with an observation tower. The Arabic name of the hill is Jebel Tuamor.

An observation tower is located on its summit, at an altitude of 624m. The tower and the garden was built in memory of Ayelet Hashachar-Levy, who was murdered in a Jerusalem terror attack on Nov 2000. Ayelet, age 28 and mother of 3, was the daughter of the Itshak Levy, the leader of the religious party Mafdal.

From the tower are great views of the area around Michmash. This sunset view is towards Jerusalem.

While descending from the hill, hundreds of black insects were observed crawling along the road. Oz Rittner (of the

Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Israel National Center for Biodiversity Studies, Tel Aviv University) identified it as “a Millipede, probably Archispirostreptus Syriacus”.

(d) Necropolis – Observation hill

A large Necropolis, with dozens of rock-cut shaft tombs, was discovered on two hills around the community (the observation post hill and the water tower hill ). The tombs are dated to the Intermediate Bronze period (2200-2000 BC).

Each grave has a vertical shaft, leading down from the ground level to burial chamber (s) at the bottom of the shaft.

The illustration below shows the cross section of a typical burial complex. The shaft leads down into a lower section, where burial chambers are cut on the side. The chambers are entered via narrow openings, which are sealed by large blocking stones. The tombs were resting places for single persons or used by the family who owned it.

Cross section of a IB/MB shaft tomb

The majority of the shaft tombs are located on the eastern side of the observation hill. The photo below shows a section of the rocky surface where the tombs are located, and in the background is the northern section of Ma’ale Michmash.

The following photos show a sample of the many shaft tombs found on the eastern side of the tower:

(e) Necropolis – Water tower hill

Another set of MB/IB shaft tombs are located on the eastern side of the central water tank, in the northern side of Ma’ale Michmash. This photo shows a round opening to one of the tombs.

In the background is another community – the outpost of Mitzpe Danny, on the eastern side of highway #458. It was established in 1998 and part of the Mateh Binjyamin regional council.

Other openings of shaft tombs are seen in the following photos. A total of 7-8 opening are located here.

(f) Cistern and trough

Past the rear gate of Ma’ale Michmash, on the northern foothills of the observation hill and on the side of the road, is a an ancient cistern. It was reinforced with a modern cement ring and metal cover.

On its side is a stone trough – an open container used to water the herds.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- Michmash – Biblical name of a place. It may have been based on the Hebrew word ‘Michman’ – meaning: hidden (perhaps referring to the hiding caves in Nahal Michmash stream)

- Ma’ale – Hebrew for “ascent”

- Ma’ale Michmash – Hebrew for “Michmash Ascent”

- Michmas -name of the Arab village which preserved the ancient name.

- Nahal Michmash – stream of Michmash

- Wady es Suweinit (Nahal Michmash) – The valley of the acacias (Hebrew: Shitah tree)

* Nearby sites:

- Tell Suwan – Arabic: mound of flints.

- Tell Miriam – Mary’s mound.

- Bir el Jebaly – Arabic: well of the mountaineer

- Tell el Askar – Arabic: mound of the army

Links:

* External links:

- “Diagonal road from Jerusalem to Adam during the Biblical times” – Yoel Elizur, Judea and Samaria researches, 1992 (pp 111-124), Hebrew

- The Border Road between Michmash and Jericho and Excavations at Horvat Shilhah, Eretz-Israel 17, pp. 236250 (Hebrew, A. Mazar, D. Amit and Z. Ilan).

- Michmash battle – Dvir Raviv, 2009 (Hebrew)

- The battle of Michmash – Larry Wood, 2002; with map.

- Michmash fortress in the north-east border of Judea at the end of the Iron Age II – S. Riklin (pdf, Hebrew)

* Biblewalks sites:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- BibleWalks Youtube channel

- Allon road – sites along the eastern side of Judea and Samaria

BibleWalks.com – dreaming in the Bible Lands

Psagot<<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Judea site—>>>Kilya

This page was last updated on Mar 12, 2017

Sponsored Links: