Remains of a Biblical city, dated to the times of David. Its name means “two gates”, which were found in the excavations of Khirbet Qeiyafa.

Home > Sites > Judea >Elah Valley > Sha’araim (“Two Gates”)

Contents:

Overview

Location

History

Structure

Photos

* Aerial views

* View from Elah

* Western wall

* West Gate

* West

* Upper city

* South

* South Gate

* Wall

* North

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Remains of a Biblical city, dated to the times of David. Its name means “two gates”, which were actually found in the excavations. Recent excavations at Khirbet Qeiyafa (also known as the “Elah fortress”), situated on a north hill above the valley of Elah, have unearthed a fortified city with two four-chamber gates. It is dated to the end of the Iron Age I and beginning of the Iron Age II period. This dating, the unique findings, and the location – all support the identity of the site as the Biblical Sha’araim.

1 Samuel 17:52: “And the wounded of the Philistines fell down by the way to Sha’araim…”

Location:

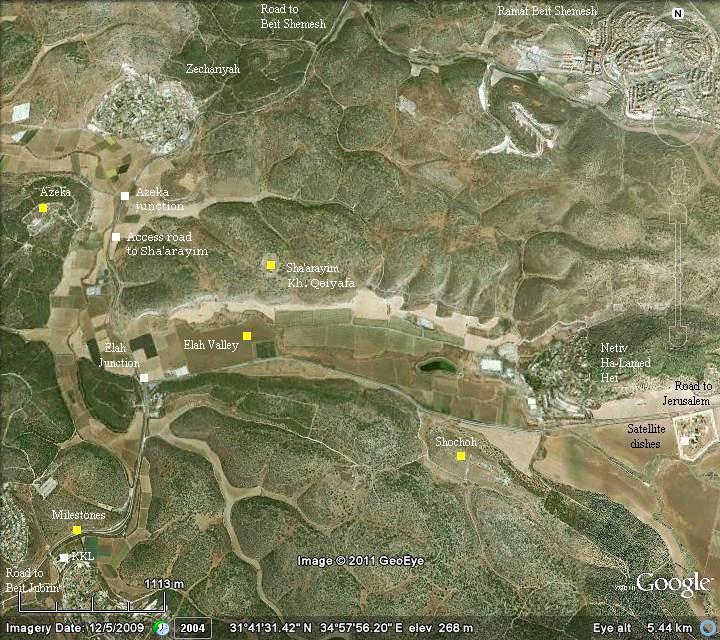

The following aerial view shows the points of interest, with the valley of Elah in the center. Khirbet Qeiyafa, which is identified as Sha’araim (Sha’arayim), is located on the north side of the middle of the valley.

The best access to the site is via a dirt road that starts 300m south of the Azeka junction.

History:

- Biblical

The city of Sha’arayim (“two gates”) was one of the cities of the tribe of Judah (Joshua 15: 20, 35-36): “This is the inheritance of the tribe of the children of Judah according to their families…. Socoh, and Azekah, And Sharaim,…”.

It is also mentioned in Chronicles, as part of the list of cities occupied by the tribe of Simeon, who co-shared cities with Judah until the reign of David (1 Chronicles 4:31): “The sons of Simeon … at Bethbirei, and at Sha’araim. These were their cities unto the reign of David”.

The city also appeared in the Biblical account of the aftermath of the battle between David and Goliath of Gath. This famous battle is detailed in the web page of the Valley of Elah. According to the Bible, Sha’araim is located near the place of the battle in the valley of Elah (1 Samuel 17: 52):

“And the men of Israel and of Judah arose, and shouted, and pursued the Philistines, until thou come to the valley, and to the gates of Ekron. And the wounded of the Philistines fell down by the way to Sha’araim, even unto Gath, and unto Ekron”.

The archaeologists found Iron Age floors in each excavated area (A,B,C,D). Only a single Iron Age phase was found, dated to the early Iron IIa period (1000-925 BC) – the times of Judean Kings David and Solomon.

Sha’araim was probably the largest Iron age IIa city in Judea, and was abandoned during the end of the Iron age IIa – at about 925 BC. It came to an end in a sudden destruction. The reasons for the destruction was either by war, earthquake or other reasons.

-

Hellenistic/Roman/Byzantine Period

After the destruction of the Iron age city, other findings were found at the site which date to later periods. The site was fortified in the Hellenistic period (third-second century BC), reusing the earlier walls and building blocks. A Byzantine farm house or khan was later built over the large Iron Age house.

At a close proximity to Sha’arayim is another ruins, named Khirbet Aklidia. This site was settled during Roman and Byzantine periods.

-

Ottoman period – PEF survey

The area around the valley of Elah was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. The valley of Elah appears on this map of 1878 in its Arabic form – “Wadi es Sunt” (the valley of the Acacia).

The ruins of Biblical Sha’arayim is marked as Khurbet Kiafa, which is located near the height marked as 1185 ft. Their report of this place was merely: “Heaps of stones”. So these ruins did not catch the attention of the explorers until recent years.

The name of the ruins was translated in the PEF dictionary as “the ruin of tracking footsteps”.

Part of Map Sheet 17 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

-

Modern Period

In 1992 Yehuda Dagan first published an estimated plan of Kh. Kiafa (Qeiyafa), and Zvi Greenhut conducted a survey in 2001, which caught the attention of the archaeologists.

Extensive excavations of Kh. Qeiyafa started in 2007/2008 and ended in 2013. The excavators are headed by Prof. Yosef Garfunkel (Hebrew University of Jerusalem) and Mr Saar Ganor (Israeli Antiquities Authority). There are also teams and scholars from the Universities of Southern Adventist, Oakland and Virginia Commonwealth. The archaeologists unearthed a pair of gates, which fit to the name of the city and made its identification almost certain.

Structure:

The site is located on a high hill (328m) above the valley of Elah. It is built on two platforms – a lower city of 100 dunams (10 hectares) and an upper city of 30 dunams (3 hectares). There are two gates – on the west side (directed towards the Biblical city of Azekah) and a south gate (directed towards the valley of Elah and the Biblical city of Sochoh). It is completely surrounded by a 2-4 m wall built in a casemate form – double walls with a 4m chamber between them (Hebrew: “Sogarim”). The bases of the wall consisted of long and heavy blocks. The back side of the dwelling rooms touched the border of the inner casemate wall.

The following aerial view shows the points of interest.

After 4 seasons of excavations (2007-2010) the excavators dated the city to 1050-925BC (end of Iron Age I, and early Iron Age IIa). The dating was based on the analysis of olive pits found in the excavations. Other remains from later periods (Hellenistic period and a Byzantine period) were excavated at some parts of the site.

The most prominent find is an Ostracon bearing five lines with 70 letters in “Proto”-Canaanite script.

Based on the findings they determined that the fortified city was a well organized Judean Hebrew city, which existed at the times of David and Solomon. Their claims of the Judean identity are based on the cooking habits (lack of pig bones, use of baking trays), the structure of the city (residential houses abut the city wall), the existence of the two gates, the type of ceramics and finding of a Semitic inscription, an Aniconic cult in a sanctuary found in the site, the location of the site and the Biblical references. The site is indeed a remarkable Iron age city, but there are debates among scholars on its identity.

Photos:

(a) Aerial views:

A drone captured this aerial view of the south side of the city. It was captured in April 2017, after the completion of the archaeological excavations. On the top side is the south gate, which leads down to the valley of Elah.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The northern side of the ruined city is seen in the next aerial view. A second gate, on the west side, is seen on the left side of this view.

![]() The following YouTube video shows a flight over the site. The drone first descends over the summit, then follows the city wall clockwise starting from the south side. Notice the casemate form in the excavated areas – double walls 2-4m apart with 4m rooms between them. The two gates, with double chambers on each side of the gate, are seen on the west and south sides.

The following YouTube video shows a flight over the site. The drone first descends over the summit, then follows the city wall clockwise starting from the south side. Notice the casemate form in the excavated areas – double walls 2-4m apart with 4m rooms between them. The two gates, with double chambers on each side of the gate, are seen on the west and south sides.

(b) View from Elah Valley

Remains of this Biblical city, dated to the times of David, are seen towering over the valley of Elah. This view is captured from the foothills of Sochoh.

A narrow dirt road leads up to the site from the valley of Elah. Perhaps this is where the wounded Philistines fell after the battle of David vs Goliath (1 Samuel 17: 52): “And the wounded of the Philistines fell down by the way to Sha’araim …”.

(c) West of the site

Approaching the site from the west, a long wide wall stretches towards the site. Khirbet Qeiyafa is seen in the background.

(d) West gate

The aerial view shows the excavated area around the west gate.

A closer view of the area around the west gate:

The next aerial view focuses on the gate itself. As seen, two chambers flank each of the sides of the gate.

On both sides of the gate is the city wall, built in a casemate design. It consists of an outer and an inner masonry wall braced by transverse masonry partitions. This design divides the gaps between the walls into a series of chambers.

The western wall of the site is built of massive blocks, and is dated to the Iron age. Before excavating this section of the hill, a Hellenistic period wall, composed of small fieldstones, covered this wall.

The photo shows the left (north) side of the west gate. A grey line in the wall shows the height of the wall before it was reconstructed by the excavators. As seen under the first level of the blocks, the wall was built right on top of the bedrock.

A wide gate is located on this side. Two chambers are located on each side of the gate.

The next picture is a west view of the west gate. In the background is the ancient city of Azekah and a western section of the valley of Elah in the direction of Gath. A road once connected the west gate to the stream of Elah, west of the site.

On each side of the gate are two chambers. This photo shows the south west chamber.

(e) West side – Lower city

On the west gate, south and north of the west gate, are excavated sections of the dwellings structures along the wall. This area, the “lower city” of Sha’araim, was designated as “Area D” (south of the gate) and “Area B” (north of the gate). This aerial view captured the area from its south side, with the gate in the center.

The structures are well preserved Iron Age dwellings. On the floors of the rooms the excavators found installations, large quantities of pottery, and stone tools – in an excellent state of preservation.

The dwellings are built against the casemates, incorporated as part of the construction. This design – a dwelling belt along the casemate city wall – is a typical feature of urban planning in Judean cities, which supports the identity of the city as part of the Judean kingdom. Furthermore, this city is the oldest known example of this design.

The excavators in 2011 were working on this section, south of the west gate (“Area D”). The archaeological work in progress was captured in this photo.

Part of the process is shifting thru the soil in order to detect all the ceramic fragments, bones and other remains.

As the city was left suddenly, destroyed either by battle or earthquake, the archaeologist found large quantities of restorable ceramic vessels and stone tools on the floors of each room.

(g) Upper City – Acropolis

On the top of the hill is the location of the “upper city”, which covers an area of about 30 dunams (3 hectares). This aerial view towards the south focuses on the area (“Area A”).

-

Byzantine period farmhouse

A large rectangular enclosure is located in the center of this area, with several rooms on its south-west side. It was dated to the Byzantine period, and served as a farm house or a caravanserai (khan).

A cistern is located on the north side of the structure. The cement frame around the opening was added during the British mandate. The photo shows the area around the cistern, with the walls of the large structure behind it.

-

Governor’s palace

Another excavation explored a section of the upper city, south of the large Byzantine structure. A thick wall, 30m long, was exposed in parallel to the Byzantine structure. Two layers were exposed – the older layer dated to the early Iron age II period situated on the bedrock, while the upper layer is from the early Hellenistic period.

This large (35 x 42m) enclosure has several rooms on its south-west side. It may have been the governor’s palace.

The archaeological work of 2011 in this section is seen in the photo below.

(h) South

This aerial view shows the south side of the city, with the valley of Elah in the background.

Another view of the south side:

A ground view of the excavated area on the south east side is in the following photo. This area was designated as “Area C”.

Three vertical stones in a room to the east of the gate, designated as “building 5” and viewed in the photo below, may have been part of a stable.

The valley of Elah stretches to the east – just below the city. Ruins of the Biblical city of Sochoh are seen on the other side of the valley, on top of the the brown round hill in the middle of the picture.

(i) South gate

In the south-east side is a second gate, which leads down to the valley of Elah. The discovery of the second gate supported the identification of the site as “Sha’araim” – two gates.

This aerial view shows the plan of the gate, similar to the west gate. There are two chambers on each side. A casemate wall connects to the gate on both sides. An underground drain crossed the right side of the entrance, draining the runoff water out of the city and to the external road. A gate plaza is located on the west side of the gate.

In the next picture is a view of the south gate, with two chambers on both its sides. The valley of Elah is seen in the background. The covered channel is located on the west side under the gate.

A detail of one of the chambers on the east side of the gate:

View of the gate from the external side:

A stone vessel, which looks like was used for cooking, was found near the gate. This is how it looked during the excavations:

The gate after the completion of the excavations:

Excavations continued in 2011 around the gate, which was designated as “Area C”.

The area on the west side of the south gate is an open plaza. In the first building west of the gate the excavators found evidence of cult practice, as two ceramic and stone models of temples were found there.

The area west of the gate is viewed in the aerial view, with the plaza are on the right side of the gate. The casemate wall is better preserved here, at times it was preserved to 3m height.

West of the plaza, two buildings were exposed (below). The first building C10 has two wings. The west wing consists of several rooms, stone columns, installations and a stone bench. In this building the temple models were found, as well as two stone seals and numerous pottery vessels. A jar filled with ash and ~20 burnt olive pits was found and used to accurately date the destruction level.

The second building, C11, had three interior spaces: a small lobby, a large space with a hearth and limestone bathtub, and a casemate room. Two steps lead down to the entrance, here on the left. The findings included numerous pottery and stone vessels.

The prize finding on the north east corner of the large room of building C11 was a fragmented jar. It contained an inscription with Canaanite script, reading the name “Eshbaal son of Beda“. The name “Eshbaal” (meaning: man of Baal) is known from the Bible: the son of Saul and second king of Israel (1 Chronicles 8:33): “… and Saul begat Jonathan, and Malchishua, and Abinadab, and Eshbaal”. He is also known by the name Ishboshet, the rival king of David (2 Samuel 2).

(j) Walls around the city

An aerial view of the eastern side of the city is seen below. It is yet un-excavated. Notice the city wall that is built around the hill.

The Iron Age city was protected on all sides by a 700m long casemate wall, consisting of an outer and an inner masonry wall braced by transverse masonry partitions. This inner wall is seen below in the inner line, with partially exposed large hewn blocks.

An external, lower wall, is seen on the external (far) side. It is about 1.5m thick and based on small or medium size fieldstones. This wall is dated to the Hellenistic period, and is built over the base of the Iron age wall.

Another section of the external wall is below. In the background is the valley of Elah, stretching towards the east.

An underground cistern can be seen along the road that follows the city wall:

(k) North

A new area (‘F’) was exposed on the north side of the city. The purpose of this excavation was to find a point where the casemate openings reverse their direction. Casemate openings are always located on the farther corner in a chamber adjacent to a gate, and since there are two gates in the city wall – it required to reverse the direction in one point, which was indeed found in this area.

A colonnaded building was exposed near the meeting point of the casemate openings. It was constructed in the Iron Age, used during the Late Persian/Early Hellenistic period, but also in use during the Hasmonean period.

Etymology:

* Sha’ar – Hebrew: gate.

* Sha’arayim, Sha’araim – Hebrew: two gates.

* Elah – the Hebrew name of the Terebinth (Pistacia) tree.

* Qiyafa, Kiafa – PEF dictionary: Arabic for “The ruin of tracking footsteps”.

Links:

* Archaeology:

- Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological project – Hebrew Univ. Jerusalem

- Dig summary reports (pdf): 2009 2010 2011

- Hadashot Arkheologiyot Volume 125 Year 2013 preliminary report

- Sha’araim – The gateway to the kingdom of Judah – Nadav Na’aman (Tel Aviv Univ) – disputes some of the interpretations of the Hebrew Univ. team

- Article: Archaeologists debate on whether Sha’araim provides a proof on Kingdom of David

(Hebrew; 4-2011) – recommended for reading

* Internal:

- Valley of Elah – overview

- Sochoh – a nearby Biblical city, south-east of Sha’araim

- Azekah – another Biblical city, west of Sha’araim

- Gath – Philistine city, home of Goliath

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

BibleWalks.com – Enter the gateway to the Bible

Valley of Elah <<<—previous site–<<< All Sites >>>—next Judea site—>>> Sochoh

This page was last updated on May 2, 2017 (Added new Aerial views, new photos)

Sponsored links: