Ruins of Hasmonean and Herodian palaces built in the second temple period, in the southwest area NT of Jericho.

* Site of the Month Nov 2015 *

Home > Sites > Jordan Valley> Jericho (Hasmonean and Roman city)

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* Swimming pools

* Alexander’s palace

* Twin Palaces

* Synagogue

* Herod’s 2nd Palace

* Herod’s 3rd Palace

* Kypros

Links

Etymology

Background:

This web page describes the area in Jericho near the Wadi Qelt valley, where a number of Hasmonean and Herodian winter palaces existed. This section of Jericho was built in the Second Temple period, and is often referred to as the NT (New Testament) Jericho, as opposed to the OT (Old Testament) Jericho in the north side of Jericho.

The royal winter palaces were built on the south west side of the garden city of Jericho, which was spread out on a broad area covered by date palm trees.

(Wars 4, 8: 2): “..in it many sorts of palm trees… pronounce this place to be divine…”.

Map / Aerial View:

The aerial map of the area is shown below, indicating the major sites. Wadi Qelt (Hebrew: Nahal Prat) is located on the left side, and the ancient sites are located close to the point where the valley emerges from the Judean mountains. It is close to the capital Jerusalem (25 km), and is located on a high point overlooking the plains of Jericho.

The Hasmonean palaces are located on the north side of the valley, while the Herodian palaces are located on both sides.

History:

-

Second temple period (570 BC – 70 AD)

The oasis of Jericho flourished during the second temple period, thanks to its prime location near strategic roads to Jerusalem, its winter climate, and the commercial exploitation of its precious crops – Balsam resin, Persimmon (Afersemon) and palm dates.

Josephus wrote about the “divine” area (Wars 4,Chapter 8: 2):

“There are in it many sorts of palm trees that are watered by it, different from each other in taste and name; the better sort of them, when they are pressed, yield an excellent kind of honey, not much inferior in sweetness to other honey. This country withal produces honey from bees; it also bears that balsam which is the most precious of all the fruits in that place, cypress trees also, and those that bear myrobalanum; so that he who should pronounce this place to be divine would not be mistaken, wherein is such plenty of trees produced as are very rare, and of the must excellent sort…”.

Date palm tree in Jericho

-

Hasmonean Period (167 BC – 37 BC)

The Maccabees headed the anti-Hellenization rebellion against the Greek Seleucids who controlled the land of Israel since 198 BC. After a series of successful military campaigns they took control of Judea, liberated the land and created an independent Jewish country, known as the Hasmonean Kingdom (164-63 BC as independent state, and 63-37 BC as rulers under Rome).

The Hasmonean kings built winter palaces in Jericho, and constructed fortifications along the roads to Jerusalem.

These are the six construction phases of the palaces:

-

John Hyrcanus I (reigned 134-104 BC) builds the first winter palace in Jericho

-

101 BC – His son, Alexander Janneus (reigned 104 BC- 76 BC) , builds a fortified palace on a high mound on top of his father’s palace.

-

A large pool complex with pavilion added on its east side.

-

76-67 BC – Alexander’s widow builds twin palaces for her two sons, south of her husband main palace.

-

67 BC- one of the two twin palaces was enlarged, and storage rooms added east of the pools complex.

-

~50 BC – Addition of a new elaborate bathhouse with heated ritual pool

Coin of John Hyrcanus I

The palaces continued to serve the Hasmonean kings until their destruction by a powerful earthquake of 31 BC.

- Early Roman Period (from 63 BC )

Pompey the Great captured the land in 63 BC. The Hasmonean Kingdom became a Roman state client, and its territories were rearranged by Pompey. Jericho remained in the Hasmonean Kingdom territory.

Pompey was engaged in a civil war with Julius Caesar and was killed in Egypt (48 BC). Queen Cleopatra VII, ruler of Egypt since 47 BC, became the mistress of Julius. After Julius was assassinated (44 BC), his General Mark Anthony (Marcus Antonius) became Cleopatra’s lover. Mark awarded Cleopatra with parts of the Hasmonean territories – the coast cities and Jericho.

-

Herod the Great (37 – 4 BC)

Herod the Great was a Jewish Roman client King of Israel (39 BC-4 BC). He was raised at the Hasmonean court, as his father Antipatris – son of a converted Edomite – was the chief minister of Hyrcanus II. Herod was initially appointed at the age of 25 as governor in the Galilee in 49 BC. With great political skills and good contacts with Rome, he became King of the Hasmonean Kingdom in 36 BC.

Herod initially built an alliance with Mark Anthony and Cleopatra. He had to pay taxes to Cleopatra for the area of Jericho which was given to her by Mark Anthony. Herod built his first winter palace, a modest structure reflecting his inferior status in the leased area. The plan of the this structure, built in 35 BC, was rectangular (87m by 46m), and was located 120m south of Wadi Qelt and 150m east of the edge of the foothills.

After Octavian (later called Augustus Caesar) defeated Anthony and Cleopatra in 31 BC, Herod managed to convince the new ruler of his loyalty. In 30 BC Octavian/Augustus transferred to Herod territories which were previously lost during Pompey’s arrangements and following Cleopatra’s changes, and added new cities to his territory. Jericho was now back again under Herod’s rule.

Julius Caesar visiting Cleopatra in her chamber

LOC – painting by Pinelli, Bartolomeo (1781-1835)

Herod was one of the greatest builders in the history of the Holy Land. His most famous project was to enlarge and rebuilt the second temple, making it a magnificent temple.

In Jericho, he built two additional winter palaces near the edge of the Wadi Qelt valley, overlooking the oasis of Jericho. They replaced the Hasmonean palaces, which were destroyed by the earthquake of 31 BC.

Imaginative illustration of Herod (Public domain)

Herod’s new palaces were built after regaining the territories of Jericho, in the following sequence:

30 BC – Second palace – North of Wadi Qelt, on top of the the Hasmonean palace.

14 BC – third palace – North and South of Wadi Qelt.

The palaces required special engineering solutions, including a complex network of aqueducts and pools, and new brickwork and construction techniques. Herod also protected the entrance to Wadi Qelt – the road to Jerusalem – by refortifying the Hasmonean desert fortress of Kypros and its twin fortress ( both are named Threx and Taurus).

After Herod’s death, a mutiny in Jericho was lead by Simon of Peraea, former slave of Herod, who burnt the palace (War 2 4 1-2):

“At this time there were great disturbances in the country, and that in many places… In Perea also, Simon, one of the servants to the king, relying upon the handsome appearance and tallness of his body, put a diadem upon his own head also; he also went about with a company of robbers that he had gotten together, and burnt down the royal palace that was at Jericho”.

The Syrian Governor Verus managed to quell the rebellion and bring back order to the land.

-

Roman period (1st-4th Century)

Herod Archelaus, son of Herod the Great (reign 4 BC-6 AD), inherited the area of Judea including Jericho. However, due to his cruelty, he was deposed, and the territories of Judea were then after controlled by Roman Procurators.

During the first stage of the Great revolt against the Romans (66-67 AD), the fortress of Kypros was conquered by the Jewish rebels and destroyed (Wars 2 18 6): “But as to the seditious, they took the citadel which was called Cypros, and was above Jericho, and cut the throats of the garrison, and utterly demolished the fortifications”. The revolters controlled Jericho, which was headed by Joseph son of Simon.

After the Romans legions came to crush the rebellion, Jericho was conquered by Vespasian in 68 AD (War 4 8 1-2): “…on the second day of the month Desius [Sivan]; and on the day following he came to Jericho; on which day Trajan, one of his commanders, joined him with the forces he brought out of Perea, all the places beyond Jordan being subdued already.. Hereupon a great multitude prevented their approach, and came out of Jericho, and fled to those mountainous parts that lay over against Jerusalem, while that part which was left behind was in a great measure destroyed; they also found the city desolate”.

Titus Arch, Rome – the victory procession, with the booty taken from Jerusalem,

including the seven branched candlestick

The Xth Legion was then stationed in Jericho (War 4 9 1): “AND now Vespasian had fortified all the places round about Jerusalem, and erected citadels at Jericho and Adida, and placed garrisons in them both, partly out of his own Romans, and partly out of the body of his auxiliaries”. The Herodian and Hasmonean palaces were destroyed during the Great revolt against Rome, and remained in ruins since then.

After the Great Revolt Jericho became a Roman estate, and the commercial activities continued to bring profits to the Roman owners. However, during the 2nd Century the city declined and was abandoned.

The Peutinger Map (Tabula Peutingeriana) is a medieval map which was based on a 4th century Roman military road map. The map shows the major roads, with indication of the cities, and geographic highlights (lakes, rivers, mountains, seas). Along the links are stations and distance in Roman miles. The roads are shown as brown lines between the cities and stations.

In the section shown on the right is the area of Jericho (named here by its Roman name – “Herichonte”) and Jerusalem (“Herusalem”), drawn in a rotated direction (west is on top). Both cities appear with double-house icons, implying the importance of Jericho. The Dead sea is shown on the left side (“Lac Aspaltidis”).

The road from Jericho to the north is shown on its right side, although the road from Jericho to Jerusalem is not shown.

P/O Peutinger map, section around Jericho (Herichonte)

-

Byzantine and Arab periods (4th – 20th Century)

During the Byzantine period (4th-7th century) Jericho became an important Christian city, with many monasteries located in the central area, east and north of the ruined palaces. The new town relocated from the Biblical Tel, to a site where the present modern city of Jericho is located. Wadi Qelt also became a center of desert monks, with St. George Kaziba monastery as the largest center.

On the right is a section of the Madaba mosaic map, which was discovered in 1884 in a Byzantine church in Madaba, Jordan. This ancient map, laid out in the 6th C AD, shows the map of the Holy Land, with dozens of illustrated sites, including Jericho.

Jericho (“ΙΕΡΙΧΟ”) is illustrated under the Jordan river and left of the Dead sea. Byzantine Jericho is surrounded by walls, four towers, two gates, three churches and nine palm trees. On the left is a building near the spring of Elisha (Ain es-Sultan), once the source of water of Jericho.

P/O Madaba map;

Section of area of Jericho

The city declined in the Arab period (9th century), until its was totally abandoned in the Middle ages (~14th Century). Jericho was in ruins and the once-beautiful oasis was a desert again.

-

Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 AD)

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. It appears on the map of sheet 18 and described in Volume III (pp 224-226).

A section of the map is shown below, with Wadi Qelt marked with a blue color, emerging from the Judean mountains on the left side and flowing right towards the Jordan river, crossing the area of the winter palaces. A Roman road (“Ascent of Adummim”) is marked as a double-dashed line. It starts in Jericho on the right side, passes along an eastern section of the valley, then goes in parallel to the valley en route to Jerusalem.

A number of aqueducts are also shown on the map, and a detailed plan is drawn in their report (p 223).

Part of map sheet 18 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

The survey wrongly identified the double mounds on both sides of Wadi Qelt as the Kypros fortress. We know now that these mounds are actually the ruins of the third palace of Herod (south) and the Hasmonean palace (north).

Here is what they wrote about the mounds:

“Tellul Abu el ‘Aleik -Two large artificial mounds, south of the last; one on either side of Wady Kelt. They were excavated by Captain Warren. The excavation in the northern one shows a rectangular chamber, the outer wall built of sun-dried bricks, and the interior lined with undressed stones, once covered with a coating of cement, which was not very hard or good. This chamber had apparently a door on the east, but was too much ruined to make this certain. The southern mound has remains of buildings and walls, and there are also remains of a bridge over Wady Kelt at this point. Both the bridge and the buildings are of the ‘opus reticulatum’ or masonry of small size, arranged with the diagonal of the stone in a vertical line. This is evidently Roman work. It has been suggested that these two mounds are remains of the towers of Thrax and Taurus, destroyed by Pompey, in or near Jericho. The placing of Roman Jericho in this neighborhood would agree with the identification of Beit Jubr with Cypros. Scattered stones, broken pottery, and traces of ruins are observable on both sides of Wady Kelt in this neighborhood, and the aqueducts from Wady Kelt also lead to the same site, which is not otherwise provided with water”.

-

Modern times

Initial excavations were conducted by Charles Warren (19th Century), as part of his search for the Biblical city of Jericho. This was followed by E. Sellin and C. Watzinder (1910-1911), USA teams (1950), and extensive excavations by Ehud Netzer (1973-1983).

Most of the excavated areas were covered for protection, and so the visitor to the site will see only a sample of the antiquities. Access to the sites is from the road from Wadi Qelt. Although the palaces are within area ‘C’ (Israeli municipal control), tours should be coordinated with the Army. It is also advised to join a group or tour.

Photos:

This section is ordered from the early (Hasmonean) to the last (Herodian) palaces.

All photos by Tuvia Liran.

(a) Swimming Pools of Alexander Janneus:

A set of swimming pools were part of the palace built by Alexander Janneus (Hasmonean King, 103-76BC). A staircase led to the bottom of each pool. Each pool (18m x 13m, 3.5m deep) was made of course stones on a layer of smaller stones, as seen on the edges of the pool. An aqueduct brought the water on a 6m wide ‘bridge’ in the middle of the twin pools.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

North of the pools was a large garden (70m x 60m) surrounded by colonnades. The area around the twin pools was 44m long by 42m wide, located on the south side of the complex, and east of the palace.

The pool complex was used for swimming and bathing, receptions, games and entertainment. For the latter purpose, the pools connected via a wide staircase to a large hall (23m by 17m) that overlooked the pools and gardens. It was in a form of a pavilion – an architecture term meaning a free standing structure located not far from the main structure, making it a place of pleasure.

Pools and pavilion – view from south east

These pools may have been the place where the Hasmonean Aristobulus III, the high priest and brother of Herod’s wife Mariamne, was murdered in 36 BC. Herod feared that this handsome 17-year old youth, a descendent of the Hasmonean royal house, will replace him (an outsider) as King, due to pressure of the people of Israel on Mark Anthony. Josephus wrote about the murder’s motive (Ant. XV 2):

“Now this son was one of the greatest comeliness, and was called Aristobulus… When this letter was brought to Herod, he did not think it safe for him to send one so handsome as was Aristobulus, in the prime of his life, for he was sixteen years of age, and of so noble a family, and particularly not to Antony, the principal man among the Romans, and one that would abuse him in his amours…”.

So King Herod conspired to have him drowned in the pool during a Sukkoth banquet organized by his mother.

Josephus provided a detailed account of the murder in the Jericho pools (Ant XV 3: 3):

“And now, upon the approach of the feast of tabernacles, which is a festival very much observed among us, he let those days pass over, and both he and the rest of the people were therein very merry; yet did the envy which at this time arose in him cause him to make haste to do what lie was about, and provoke him to it; for when this youth Aristobulus, who was now in the seventeenth year of his age, went up to the altar, according to the law, to offer the sacrifices, and this with the ornaments of his high priesthood, and when he performed the sacred offices, he seemed to be exceedingly comely, and taller than men usually were at that age, and to exhibit in his countenance a great deal of that high family he was sprung from, – a warm zeal and affection towards him appeared among the people, and the memory of the actions of his grandfather Aristobulus was fresh in their minds; and their affections got so far the mastery of them, that they could not forbear to show their inclinations to him. They at once rejoiced and were confounded, and mingled with good wishes their joyful acclamations which they made to him, till the good-will of the multitude was made too evident; and they more rashly proclaimed the happiness they had received from his family than was fit under a monarchy to have done. Upon all this, Herod resolved to complete what he had intended against the young man. When therefore the festival was over, and he was feasting at Jericho with Alexandra, who entertained them there, he was then very pleasant with the young man, and drew him into a lonely place, and at the same time played with him in a juvenile and ludicrous manner. Now the nature of that place was hotter than ordinary; so they went out in a body, and of a sudden, and in a vein of madness; and as they stood by the fish-ponds, of which there were large ones about the house, they went to cool themselves [by bathing], because it was in the midst of a hot day. At first they were only spectators of Herod’s servants and acquaintance as they were swimming; but after a while, the young man, at the instigation of Herod, went into the water among them, while such of Herod’s acquaintance, as he had appointed to do it, dipped him as he was swimming, and plunged him under water, in the dark of the evening, as if it had been done in sport only; nor did they desist till he was entirely suffocated. And thus was Aristobulus murdered, having lived no more in all than eighteen years, and kept the high priesthood one year only; which high priesthood Ananelus now recovered again”.

The following photo shows debris of columns, close to the pavilion foundations.

(b) Palace of Alexander Janneus:

West of the pavilion and pools complex was a high mound surrounded by a deep moat. Here was a fortified palace, which was built by Alexander Janneus on top of an earlier palace built by his father John Hyrcanus.

The palace was protected by a 7m deep moat, 5m tall walls, and 3m high towers – a total of 15m high glacis wall. The entrance to the palace was from the pools complex on the northeast side. Water supply to the top of the palace was arranged by means of a siphon system, using ceramic pipes which can be seen in the remains of the mound. The waters came from an aqueduct system starting 400m west of the palace, where two aqueducts converged.

Illustration of Alexander’s palace – view from south east

Alexander’s aim in fortifying the palace and placing it on a high hill was to better protect it and enhance the views from the palace, as it was located in the dense area of date palms.

Sections of the palace and a ritual bath (in the far side) are seen in the following photo. The pools received the water from the Dok (Dagon) fortress and Wadi Qelt via an aqueduct, coming from the hill on the far right side.

The fortified palace and the pool complex were built at ~100BC. They were destroyed by the great earthquake of 31 BC. Few remains exist from these structures.

(c) Twin palaces of Queen Alexandra:

Queen Alexandra Salome (Shlomzion), widow of Alexander, reigned from 76 BC until 67 BC. Her sons, John Hyrcanus II and Aristobolus II, were positioned to succeed Alexandra, and she intended to ease the tension between the rival brothers. Therefore, she constructed twin identical palaces adjacent to the fortified palace and south of her husband’s swimming pools.

Both palaces, with a mirror images of each other, had a rectangular plan of 26m by 23m area. A 4.5m section separated the two palaces. In the center of each palace was a 10m by 9m courtyard, surrounded by rooms on all sides.

Illustration of Alexander’s palace – view from south east

A garden with a swimming pool in its center was located near each mansion. The garden sizes and pool sizes were not identical – 32m x 19m garden with a 8m x 8m pool on the western mansion, and 40m x 25m and 7m square pool on the eastern mansion.

The following photos show different sections of this area. A western view, with the edge of Wadi Qelt in the background:

The same area with a north western view:

More details on the excavated palaces:

The structures include industrial and agricultural installations.

The Royal estate and its vicinity included wine presses (made from dates) and installations for the manufacturing of perfumes (made of the balsam shrubs). The irrigation required constructing an elaborate system of aqueducts and reservoirs.

There are also ritual baths (Mikveh), some of these are in excellent condition:

Another view of this beautiful ritual bath:

Other ritual baths, with separate steps from descending and ascending (after purifying):

After Alexandra’s death (67 BC), her son John Hyrcanus II was named the heir, but Aristobulus II defeated his brother and ascended to the throne 3 months later. Although their mother could not prevent the clash between the brothers, at least the deposed brother was spared, allowed to benefit from his title as the chief priest. During his time, a new large pool (20m x 12.5m) was constructed to the east of the twin palaces. The entrance to this pool was from the garden of the eastern mansion, probably belonging to degraded Hyrcanus II who could not enjoy the swimming pools of the main palace.

(d) Ancient Synagogue:

Near the ruins of the Hasmonean Royal winter palace are the remains of the oldest known synagogue in Israel. It was built between the years 75-50 BC, probably during the reign of Queen Salome Alexandra (Shlomzion, reigned 76-67 BC, widow of Alexander Jannaeus).

The structure complex covered an area of 28m by 20m, and was developed in 2-3 stages. It is made of mud bricks on a foundation of field stones, and includes a ritual bathing area, a courtyard flanked by seven-eight rooms, a genizah (storage of worn-out scrolls), and a rectangular main hall (16m by 11m) surrounded by a colonnade of 12 pillars resting on a raised platform. The platform supported a seating of 70 people. It is oriented to the west, facing Jerusalem, as in this photo.

The synagogue complex and the palace were destroyed by the major earthquake of 31 BC (magnitude 7) which devastated the cities in the Western Jordan valley (such as Masada, Qumran and Jericho). Josephus Flavius wrote about this powerful quake (Ant. XV, Chapter 5): “At this time it was that the fight happened at Actium [BW: 31 BC], between Octavius Caesar and Antony, in the seventh year of the reign of Herod and then it was also that there was an earthquake in Judea, such a one as had not happened at any other time, and which earthquake brought a great destruction upon the cattle in that country. About ten thousand men also perished by the fall of houses…”.

Herod the Great rebuilt a new palace (his second) above the ruins of this synagogue, which was never rebuilt.

(e) Herod’s Second palace:

Herod the Great built a new palace in 30 BC on the north side of Wadi Qelt. His palace also was laid over the ruins of the Hasmonean palace and the twin mansions, which were severely destroyed by the earthquake and fire. The Hasmonean twin pools were now reconstructed to form a single pool, 32m by 18m in size. The main palace was constructed to the east of the pavilion and pool. It had two wings –

-

a north wing 58m x 33m in size, built around a courtyard (26m x 20m) surrounded on all sides by colonnades. On its south side was a Roman style dining room (triclinium).

-

a south wing with a pool, surrounded on all sides by colonnades, and rooms on its south side.

The second palace continued to function together with Herod’s third palace.

(f) Herod’s third palace:

Herod built a new (third) palace at the end of his reign, at ~14BC. Its location is close to Herod’s first palace, which is located 100m to the south. The new palace was planned at a greater scale, as Herod formally received the area of Jericho from Augustus in 30 BC and could boast his new status with these grand constructions.

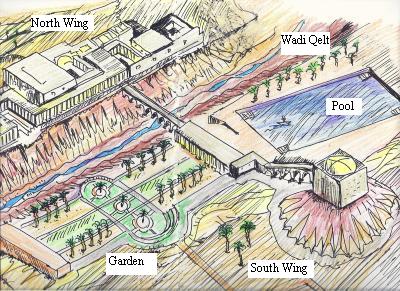

The grand palace, covering an area of 30 Dunam (7.5 acres), was composed of two wings across both sides of the valley of the Qelt stream. In this illustration, the palace is viewed from the south west, with Wadi Qelt in the middle flowing left to right.

Pools and pavilion – view from south east

On the north wing was the main palace. On the south wing was a high mound, where the royal reception hall was located. A bridge over the valley connected both sides.

To the west of the south wing, along Wadi Qelt, was a large decorative garden named “the sunken garden”. It was bounded inside a rectangular structure, 145m in length and 40m in width. The south walls were sunken into the hillside, and had 48 decorative niches. In the center of the southern wall was large circular stepped structure, with plants growing in multiple levels.

To the east of the southern mound was a large (90m x 42m) pool, which was used for swimming and sailing with small boats.

The photo below, with a view towards the north east, shows the northern wing of the palace, with the stream passing on its south (right) side.

The valley is dry, but during the winter time there are 2-3 occasional flooding events. The water supply to the palace and the gardens was therefore based on a network of aqueducts that conveyed spring water from several sources into reservoirs.

The southern wing is built on an raised mound, seen across the valley in the upper side of the photo below. Inside this artificial mound are the ruins of a square structure (19.5 x 20.5m) that was a base of a large (16m diameter) circular reception hall. It served as a royal reception house, offering an elevated platform to view the Jericho oasis, which was covered by date palm trees.

A staircase bridge over the valley connected both wings.

The ruins of the Herodian palace were located on both sides of Wadi Qelt, and named “Tell Abu el’Aleik” – meaning in Arabic: “The mounds where the barky grows round them” (as per PEF glossary, p. 352).

- North wing

A closer view of the northern wing of the third Herodian palace is seen below. The northern wing included rooms, halls, courtyards and a large bathhouse.

- Large open courtyard

On the west side of the palace is a large open court, surrounded by columns on three sides. It is indicated on the illustration.

Pools and pavilion – view from south east

The Corinthian columns once supported the roof above. This large (29m x 19m) hall served as a reception hall and used also for feasts. It is the largest Roman hall found in Israel!

A view of the remains of the columns is seen in the photo below.

The walls of the hall were covered with stucco (decorative coating) and frescoes (paintings). The columns were supported on pedestals.

The floor of the courtyard was paved with local stone tiles, now gone. The stone blocks that once were laid on the floor were stolen, but left marks on the ground. The floor was of the type “opus sectile”, a style common in Rome during the 1st Century BC, based on rough geometric cuttings of various colored stones.

The entrance to the hall was wide, 5.5m, opening the hall to the view outside.

The walls of the palace are built on a brickwork form called “Opus reticulatum” (Latin for “net work”) – small square blocks resting on a core of cement, set in a diagonal 45 degrees pattern.

The diagonal Opus-Reticulatum brickwork construction, common in the 1st Century Rome, is rare in Israel, and was probably built by Roman bricklayers. In the photo below are two forms of brickwork – the diagonal on the right (Opus reticulatum) and the flat blocks on the edge of the wall (Opus Quadratum, a classic form of bricklaying).

The Romans later replaced this technique with an alternative form called “Opus latericium” (Latin for “brick work”) which dominated the construction style at the end of the first Century BC. It was based on flat bricks laid on a core of concrete.

The palace included two additional courtyards, a small hall, and several rooms.

- Bathhouse

A Roman bathhouse complex is located on the east side of the palace. It was composed of several rooms – a cold, warm and hot baths, waiting and entrance room.

Pools and pavilion – view from south east

In the photo below is an east view of a section of what remained from the bathhouse, with the open court behind it.

The impressive element is the round base of the circular frigidarium (cold room). It has four semicircular niches in each of its corners. This room was entered after the hot (caldarium) and warm (tepidarium) rooms of the bathhouse.

- West and East

On the western and eastern sides of the palace were additional sections, which included residential rooms and stores, bathhouse, installations, gardens and pools. Some of these structures may have been constructed 10-15 years before the third palace, and were incorporated into the new palace.

The Herodian and Hasmonean palaces were destroyed during the Great revolt against Rome, and remained in ruins since then.

(g) View from Kypros:

South West of Jericho, above Wadi Qelt, are the ruins of Kypros (Cyprus), a desert fortress built by the Hasmoneans. The fortress was one of two Hasmonean desert forts (named Threx and Taurus, as per Strabo xvi. 2, 40) that sealed the north and south sides of the entrance to Wadi Qelt – an important route to Jerusalem.

A great view of Jericho is seen from the fortress.

Kypros was first built during the Hasmonean Kingdom, probably in 120BC by John Hyrcanus (reigned 134-104 BC). Josephus Flavius wrote (Wars 1 8 2): “He (Hyrcanus) also built walls about proper places… that lay upon the mountains of Arabia”. The purpose of this fortress, as well as the other six desert fortresses, was to protect the eastern border of the Jewish Kingdom against the Edomites and other threats from the east. These fortresses had additional designations – they served as palaces, protected royal treasures, stored supplies and weapons, and also functioned as prisons.

The fortress was probably destroyed by Pompey the Great during the Roman conquest in 63 BC. It was later refortified by Herod the Great, and named after his mother.

The section of the Hasmonean and Herodian palaces lies east (right) of the edge of the valley. In the far background are other neighborhoods of modern Jericho, where the ancient Biblical mounds are located.

Here is a panoramic view of the plains of Jericho:

Links:

* External links:

- Hasmonean palaces – Information and Video (Hebrew)

- Purpose of the Hasmonean desert fortresses (Hebrew, pdf 10 pages)

- Synagogue exposed in Jericho – Ehud Netzer

- The Palaces of the Hasmoneans and Herod the Great Part 1 Part 2 – Ehud Netzer, Israel Exploration Society

- Tagliot – “Archaeology for All” (Hebrew site) – arranged the tour, which was guided by guided by Dvir Raviv.

* Internal Links:

- Jordan-Jericho – The southern section of the Jordan river near the Dead sea. A traditional site of the Israelite crossing site to the Holy Land, Elijah’s departure, baptize of Jesus by John, and location of many monasteries and chapels.

- St. George Koziba, Wadi Qelt – St. George Koziba is a cliff hanging Byzantine monastery in the valley of Wadi Qelt, near Jericho.

Etymology – behind the name:

- “Tell Abu el’Aleik” – the double mounds of the Herodian palace. It means in Arabic: “The mounds where the barky grows round them” (as per PEF glossary, p. 352).

- Jericho – one of the earliest cities in the World. Probable source of the name is “Moon City” as the Hebrew name is Yericho, based on the Hebrew root name Yerach (moon). Perhaps, the early residents worshipped the moon. Or, the place where the moon was first seen.

BibleWalks.com – walks along the Jordan river

Tel Issachar <<<—previous Jordan valley site—<<<All Sites>>>

This page was last updated on Sep 15, 2015

Sponsored Links: