A 2nd century BC Hasmonean desert fortress in the northern Judean desert. It was reinforced by King Herod the Great. During the Byzantine period a Monastery was built by the Judean monks.

* Feb 2013: new photos added *

Home > Sites > Judea > Horkania (Hyrcania)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Plan

Photos

* General

* Walking up the hill

* Fortress and Monastery

* Panorama

* Cisterns

* Aqueduct

* North West side

* East Side

* South West side

* Reservoirs

* Necropolis

* Flowers

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Horkania (Hyrcania) is one of the seven desert fortresses constructed by the Hasmonean Kings during the 2nd century BC, and reinforced by King Herod. It raises 200m above the valley of Horkania, on the northern Judean desert. During the Byzantine period a Monastery was built on the ruins of the fortress by the Judean monks.

Location and Aerial map:

The site is located in the Judean desert, 16 KM east-south-east of Jerusalem. The hill is 248m above sea level.

The aerial map below shows the location of Horkania, with the north side directed to the left.

History of the place:

-

Hasmonean Kingdom period

The fortress was built during the Hasmonean Kingdom, probably in 120BC by John Hyrcanus (reigned 134-104 BC), and is named after him. The purpose of Horkania, as well as the other six desert fortresses, was to protect the eastern border of the Jewish Kingdom against the Edomites and other threats from the east. Josephus Flavius (Wars 1 8 2): “He (Hyrcanus) also built walls about proper places; Alexandrium, and Hyrcanium, and Machorus, that lay upon the mountains of Arabia”. These fortresses had additional designations – they served as palaces, protected royal treasures, stored supplies and weapons, and also functioned as prisons.

Queen Shlomzion (Alexandra), the widow of Alexander Jannaeus (Yannai), stored goods in the fortress and did not pass it to her sons (Josephus Flavius, Ant 13 16 3): “So Alexandra… committed the fortresses to them, all but Hyrcania, and Alexandrium, and Macherus, where her principal treasures were.”.

The cities and roads during the Canaanite, Israelite and Hasmonean periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below, with Horkania/Hyrcania in the center. An ancient desert road passed nearby: from Bethlehem or Jerusalem, down the Kidron stream thru Mar Saba, to the valley of Horkania below the fortress, then north-east to to the Dead Sea and Qumran.

Map of the area around Horkania/Hyrcania – during the Canaanite, Israelite and Hasmonean periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

-

Early Roman Period

Pompey: The Roman forces, headed by Pompey the great, destroyed Hasmonean fortresses in 63 BC, including Horkania. According to Greek geographer Strabo (Book 16 2 40): “Pompey went over and overthrew them and razed their fortifications… Alexandrium and Hyrcanium and Machaerus and Lysias…”.

Alexander II: The fortress was later rebuilt by Alexander II, son of Aristobulus, during his mutiny against the Romans (57 BC). Josephus wrote about these events (Wars 1 8 2):

“But as for Alexander, that son of Aristobulus who ran away from Pompey, in some time he got a considerable band of men together, and lay heavy upon Hyrcanus, …. He also built walls about proper places; Alexandrium, and Hyrcanium, and Machorus, that lay upon the mountains of Arabia”.

Aulus Gabinius, Roman general under Pompey, managed to overcome this mutiny and destroyed the fortress to prevent its use in future mutinies (Wars 1 8 5): “When Gabinius … returned to Alexandrium, and pressed on the siege. So when Alexander despaired of ever obtaining the government, he sent ambassadors to him, and prayed him to forgive what he had offended him in, and gave up to him the remaining fortresses, Hyrcanium and Macherus, as he put Alexandrium into his hands afterwards; all which Gabinius demolished, at the persuasion of Alexander’s mother, that they might not be receptacles of men in a second war”.

After the fortress was rebuilt, Alexander revolted again (55BC), but this time the fortress was not harmed.

Herod the Great: Herod the Great, the Jewish Roman client King under the Romans(37BC-4BC), fortified and enlarged Horkonia (Josephus Flavius, Ant 16 2 1): “…he had built, and at the fortresses which he had erected at great expenses, Alexandrium, and Herodium, and Hyrcania“.

During a mutiny against Herod (33-32 BC), headed by a Hasmonean princess, the fortress was used by the rebels as a stronghold. However, Herod re-conquered the fortress (Wars 1 19 1): “as being already freed from his troubles in Judea, and having gained Hyrcania, which was a place that was held by Antigonus’s sister.”.

Herod locked up his enemies in the fortress and killed them (Ant 15 10 4): …”and many there were who were brought to the citadel Hyrcania, both openly and secretly, and were there put to death;”. Herod killed most of his family, including his son and heir Antipater at the last days of his life (Wars 1 33 7): “Herod… sent some of his guards and slew Antipater; he also gave order to have him buried at Hyrcanium“. After five days (in 4 BC) the great (although cruel) King died, after 34 years as the “King of the Jews”.

During the great revolt against the Romans, it is not known if Horkonia was part of the battles.

-

Byzantine period

Starting in the end of the 4th century, monks started to populate the caves of the Judean desert. The Byzantine monks came here to seek the simplicity, purification and the solitude of the desert.

The Byzantine monks reused the stones of the ruined fortress to build a monastery, including an underground church. The first residence on the site was by St. Sabbas, one of the most important figures of the desert monasticism. It was established in 492AD when Sabbas was 53 year old. It was called “Castellion”, named after the ruined desert castle. After the 6th C the place was called Marda, which also means castle. Later, the Arabs called it el-Mirad.

Sabas helped to establish more monasteries in the desert: He and his monks established during this time a total of 13 (!) monasteries in the Judean desert. Several older monasteries came under his management – including the famous Monasteries of Euthemius (in Mishor Adumim) and Theoktistus (in nearby upper Nahal Og).

St. Sabbas – painting in St. Gerassimos

The Castellion was a form called “Coenobium” (pronounced Coi-Noi-Bee-Yum), which was a communal monastery, where a number of structures were surrounded by a wall and the monks lived there in a commune. The monks lodged inside the compound and followed a strict daily schedule. This word is based on the Greek words Koinos (common) and Bios (Life). The emphasis of this form is the community life, in contrast with the solitary living of the hermits which was too lonely and often led to mental breakdown. It was larger, more disciplined than the Laura, and followed a daily schedule. For many hermits, it was the first station before wandering to the desert or joining a Laura.

The Castellion was part of the Laura (Lavra) of Mar Saba (named after Sabbas) monastery, which was a cluster of caves or cells of hermits residing around a central monastery. The monks met in the center on Saturdays and Sundays, while in the rest of the days they lived in seclusion.

The hermits resided in the Castellion monastery until the 14th C, then the site was deserted until the 20th C.

-

Ottoman Period

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine in 1873. They reported on their account of Horkania (SWP, Vol 3, p 212):

Khurbet Mird (Mons Mardes)”A ruin in a very strong natural position on a precipitous hill, standing 1,000 feet above the level of the plain east of it. The site is divided on the west from the main line of the cliffs by a low saddle, and the road here approaches along a very narrow ledge of rock. An aqueduct, which appears to collect surface drainage on the slopes of Muntar and connected with the Bir el ‘Ammara, forms the water supply of the present ruin. It is partly tunneled in the rock, partly of masonry, the channel, 1foot 6inches wide, lined with hard white cement. The aqueduct crosses the saddle along a narrow ledge of rock, and once supplied two pools, or Burak, 30 to 40 feet square, north of its course in the saddle.

There is also a well on the north of the ruin, and another on the south, which is ruined. There is a wall to the birkeh at the saddle, built in a series of steps of masonry about 1 foot square and hard mortar. The cisterns in the ruin are lined with very hard white cement. Masonry tombs are said to exist among the ruins. The largest cistern is about 30 feet deep. Vaults with semicircular arches were observed, and walls of small masonry. The site is evidently that of a town of some importance, and the buildings resemble Byzantine ruins in other parts of the country”.

Part of map Sheet 18 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

- Modern times

According to some interpretations of the Qumran copper scroll, their treasures are hidden here in Horkania. So treasure hunters and expeditions are trying to find them in the past 50 years. This mystery and quest makes the remote desert fortress of Horkania even more interesting.

The site was not yet excavated. A survey was conducted here in 1960 by John Allegro, who was responsible for the opening and deciphering the copper scroll.

Another survey was conducted by the staff of the Ein Gedi field school, who thoroughly mapped the site.

Getting there: This remote site is in ruins and is accessible only by 4×4 vehicles, bikers or hikers.

The winter weekends are the perfect time to come here. At the time of our visit to the site (Jan 2013) the fortress was virtually crowded with several organized tours, nature clubs, and mountain bikers.

Plan:

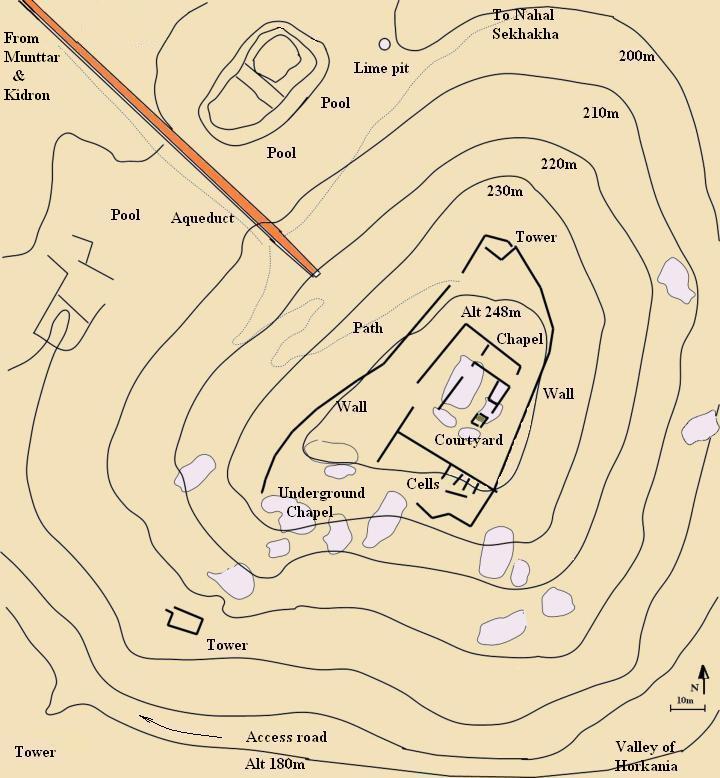

The plan of the site is illustrated here. The access road approaches the site from the south-east, passing between two towers.

The aqueduct reaches the hill on the north west side, and was used to fill up the cisterns on the south and east side of the hill via channels dug around the hill. Its overflow waters were stored in 3 pools on either side. An access path rises from the aqueduct to the top of the hill, where the ruins of the fortress and monastery are located. Around the top is a wall.

Photos:

(a) General view

A view from the valley of Horkonia, on the south-east side of the site, is seen in the following photo. A herd of camels are seen in the foreground.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

You can also see this photo in 3D – click here and a new window will open up with the special picture. Then, use the standard (red-cyan) 3D glasses to view it. Focus on the camels and they will pop out in front of the background. If it doesn’t work, well, you should go out to the desert yourself to view it in natural 3D…

A closer view of the fortress from the south-east is seen in the next picture. Notice the traces of the walls on top of the hill, covering an total area of 120m x 60m.

Another north-east view of the hill of Horkania, with a Bedouin riding his donkey along the entrance to Nahal Sekhakha.

(b) Walking up

The walk up from the valley to the fortress is not easy. At the section along the foothills the ascent requires some considerable sweat, but as can seen here – even an elder woman attempts the climb.

The trail leads up to the southern side of the mountain, reaching the point where the aqueduct connects to the foothill. Then, a twisted path leads up to the top.

Mountain bikers of course take the challenge with a smile. This biker, part of a group of 20 bikers, climbed up the mountain with no problem and enjoyed the effort.

(c) The fortress and Monastery

The walls of the fortress are visible along the peripheral of the top of the hill. Along the wall was the dining area (refectory) and assembly hall of the monastery.

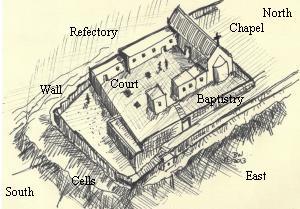

During the Byzantine period the ruins of the fortress were converted to a monastery. An illustrated reconstruction of the monastery is here, with a view towards the north. The chapel is located on the north side, the court on the south side, and the dining room on the west side.

Reconstruction of Monastery in Horkania

The picture below shows the eastern side of the top of the hill, with remains of the floor of the monastery’s court yard. The total size of the monastery on the top side of the hill is 40m x 25m. There are rooms to the east, north and west of the center of this complex.

The church is located on the north-east side of the complex, at the top of the hill. Its location is indicated as a red square on the map.

The base of the church is seen below, with its altar oriented to the east. A baptistery was located to the right of the chapel.

The floor was covered by colorful mosaics, and only few sections survived. Its stones are small (1cm x 1cm), and dated to the 5th-6th century AD.

A 360 degrees panoramic view, as seen from the top of the hill, is shown in the following picture. If you press on it, a panoramic viewer will pop up. Using this flash-based panoramic viewer, you can move around and zoom in and out, and view the site in full screen mode.

To open the viewer, simply click on the photo below. It will open a new window after a minute or so.

(d) Cisterns and underground chambers

In the court area of the church are two underground cisterns, with a plastered surface. The floor of the church rested on top of an arch. These vaults were probably constructed by Herod, who expanded the area on top of the hill by extending the flat area towards the east.

The entrance to the other cistern is in the picture below:

Access to the chamber is seen here. There were about 20 cisterns in the area of the fortress, some of them were converted to residence cells for the monks.

-

Underground chapel:

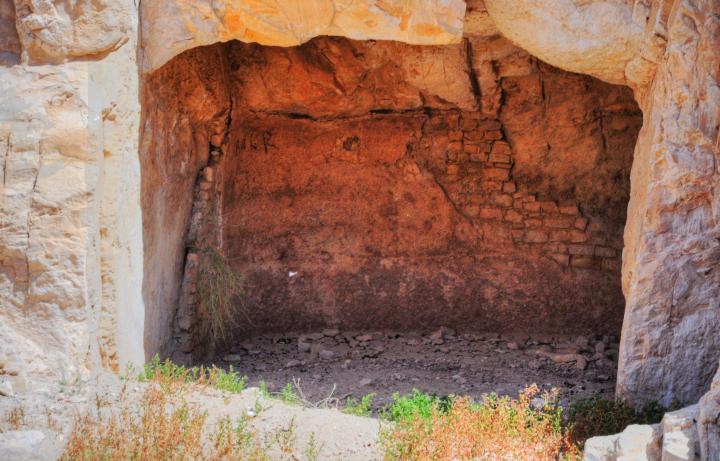

An underground chamber on the south-western corner of the complex was originally a burial complex, then reused as a chapel by the Byzantine monks in the 8th to 10th C.

Its location is indicated as a red square on the map, and is seen in the following photo.

Inside the cave are few remains of the ancient chapel. The cave was cleaned and repainted in 1925, but damaged by the Bedouins in 1939. In 1952-1953 a number of Byzantine manuscripts were found here by Bedouins, followed by a salvage expedition. Other artifacts are stored in the monastery of Mar Saba.

An adjacent entrance to a chamber is harder to get in or out. On its walls were once colorful frescoes – painting executed on freshly laid lime plaster. The paintings are dated to the Byzantine period, and included illustration of 36 Byzantine famous desert monks.

(e) Aqueduct

The Judean desert is very dry, and the supply of water was one of the important engineering projects that were required to keep the fortress alive. There were two aqueducts that supplied water to the fortress. A shorter north-west aqueduct brought water from a dam across Nahal Sekhakha, on the eastern hillside of Jabal Munttar. A longer channel diverted water from the Kidron stream, south-west of Horkonia. Both aqueducts joined together at a some point and delivered their waters through this final section.

The aqueduct reaches the hill on this north-west side. In the past, there were two channels that let the water flow around the hill in order to fill up more than a dozen of cisterns on the south and east sides of the fortress.

The base of the aqueduct is Hasmonean (Hellenistic period), as attested by the headers and stretchers pattern (Hebrew: “Rashim & Patinim”), where the stones are laid in vertical and horizontal structure. The headers are 20cm wide while the stretchers are 75cm long.

The upper level of the aqueduct is Herodian (Roman), and probably with Byzantine period reworks.

Three large water reservoirs are located on the west side of the fortress. They served as overflow pools.

The aqueduct’s location is illustrated here and marked by a red square, and the three pools are cut into the rock around it on the bottom of the hill.

The size of the reservoir to the left (south) of the aqueduct is 30m x 70m, the central reservoir is 20m x 22m, and the right (north) one is 18m x 20m.

In the far background is Mount Munttar, one of the sources for the aqueduct.

During the winter time the rainfall was collected, brought in by the aqueduct, and filled up these pools. These rock-hewn pools stored the water for the entire year, and also added protection for the western side of the fortress.

A view of the aqueduct from the north-east side, and the southern reservoir, is seen below. Above it, on top of the hill, are caves where some of the Byzantine monks used to reside most of the time in total seclusion.

The next picture is a closer view of the southern reservoir, with a view towards the east.

- Following the source of the water:

We walked along the aqueduct towards the west, in order to get to Nahal Sekhakha from an easier path. The first section near the fortress crosses the valley along the high bridge.

The next photo is from a location east of Horkania, where the water channel followed the contour of the hill. The track of the aqueduct at this point is flat and easy to follow.

Some of the sections of the aqueduct crosses valleys, while other sections are raised by walls in order to maintain a constant shallow angle, which is required in order to supply the water along a large distance from its sources.

- Aqueduct from Kidron:

There are two channels that fed the aqueduct – one from Munttar, while the longer from Kidron. These two channels flow in parallel (as seen here in the double tracks) before they join together and reach the fortress.

The next photo shows a section of the southern (and longer) aqueduct from Kidron. You can notice traces of a wall that crosses the valley in the center of the picture.

(f) North West side of the hill

On the north west side of the hill, to the north of the aqueduct, are the two water pools, a lime kiln, and additional seclusion caves.

In this picture – Dror, the energetic manager of Tagliot who organized this tour, stands on the edge of the lime pit.

The location of the lime kiln is indicated on the map by a red marker.

A closer look to the pit is below. This was a kiln, which used to burn limestone in order to produce Calcium oxide (aka, quicklime or burnt lime). The lime was then used as a sealant to cover the surfaces of the cisterns, thus preserving the water in the reservoirs. It was also used as a key ingredient for making cement.

(g) Eastern side

The eastern side offers great views of the Horkania valley. On this steep side are remains of the peripheral wall and a dozen or so cisterns that stored the water from the aqueduct. Some of these chambers were converted to cells for the monks.

(h) South Western side

The main entrance to the fortress is from a road that follows the valley on its south-western side. This road is seen here where the jeeps attempted to climb up along the valley, but returned back due to the impossible slopes.

On the south side of the road is a high watch tower, seen here on the right side.

A closer view of the watch tower:

Another tower is located on the north side of the road. This Herodian structure has a 10m square base.

(i) Water Reservoirs

Additional water reservoirs collected rainwater in the bottom of the valley on the west side of Horkonia. They are seen below.

A closer view of the reservoir:

Another water reservoir is located in the valley of Nahal Sekhakha, north of Horkania. This also served the Byzantine monks who resided in the caves around the valley. This site is detailed in a separate page.

(j) Necropolis

The Necropolis (“City of the Dead”) of Horkania is located in the hills above the Sekhakha valley, about 500m east of Horkania. This photo shows a number of the tombs on the ridge above the valley.

A closer view of the tombs on the bottom-right corner is shown in the following picture. All the tombs were opened by grave diggers in order to locate treasures and artifacts.

The tombs date to the Hasmonean and early Roman period.

Another view of the other ridge shows a square structure, which was a Roman camp and part of a siege wall. The wall and camp were probably built in 57 BC by Gabinius during the Hasmonean mutiny of king Alexander II (Wars 1 8 5): “When Gabinius … pressed on the siege…… gave up to him the remaining fortresses, Hyrcanium and Macherus, … “.

(k) Desert Flowers

During winter time, which brings occasional rain drops, you can enjoy the blossoms of desert flowers, such as this one (unidentified) on the south walls of the fortress.

The next picture shows another desert flower, identified by Uncle Ronnie as “Desertorum Bellevalia” (Hebrew: Zamzumit Hamidbar”). This desert flower is found in Jordan, Judea, Negev and Sinai. It blooms in winter. The species is named after the French botanist Pierre Richer de Belleval.

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the site:

- Horkania, Hyrcanium, Hyrcania – names of the fortress, named after Hasmonean King Hyrcanus.

- Castellion – The name of the Byzantine monastery, based on “castle”

- Marda – the Syrian-Aramaic name, means also “castle”.

- Merd, Mert, el-Mirda – Arabic name of the site. Based either on the Syrian word Marda – fortress, or on the sons of Judah (1 Chronicles 4 17): “And the sons of Ezra were, Jether, and Mered, and Epher, and Jalon: and she bare Miriam, and Shammai, and Ishbah the father of Eshtemoa”.

- Valley of Horkania – In Arabic: el Bukeia

Links:

* External:

- The real designation of the desert fortresses (pdf; Hebrew; pp 7-16) – The author proposes that Horkania, as well as other Hasmonean desert fortresses, served mainly as safe places for royal treasures and logistic center for their army.

* Internal:

- Mar Saba nearby monastery

- Munttar nearby mountain, place of the scapegoat

- Nebi Musa nearby ancient Holy Muslim site

- Nahal Sekhakha nearby monastery and mysterious tunnels

- Secacah was it in nearby Karem es Samra?

- Byzantine monks – info page on Monasticism

- Aqueducts in other ancient sites

BibleWalks.com – Have Bible, will Travel!

Munttar <<<—previous site—<<< All Sites >>>—next Judea site—>>> Nahal Sekhakha

This page was last updated on Mar 1, 2013

Sponsored links: