Ruins of a Roman/Byzantine period village, located near a large spring on the foothills of Mt. Baal-Hazor. A unique Middle Bronze cemetery is located on its south side.

Home > Sites > Samaria > Allon Road > Kh. Samiya (Samiyeh)

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Photos

* Aerial views

* Ground views

* Spring

* Mill

* Samiya valley

* Necropolis

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Ruins of a Roman/Byzantine period village, located near the rich Samiya spring on the foothills of Mt. Baal-Hazor in the eastern Samaria desert region.

A unique Middle Bronze cemetery is located on its south side.

On the north east side of the spring, on a high fortified hill, are remains of a Canaanite and Israelite city, which are featured on a separate page.

Location and Map:

A map of the area is shown here, indicating the major points of interest. The site is near the Allon Road, 3KM north of Kokhav Hashahar settlement. It is located on a height of 437m above sea level, at the north eastern foothills of the high mountain of Baal-Hazor (1016m altitude).

Kh. Simiya is accessed by a paved road that leads to the Samiya spring, where a modern pump station is located. Its ruins are located along the access road.

The fertile Samiya valley flows to the east, through the deep winding valley of the Yitav stream (Arabic: Wady ‘Aujah, or Ujah – meaning the crooked or bending valley). It reaches the Jordan valley and river 10 km north of Jericho.

History:

-

Bronze age (30th-12th century BC)

The site was first settled during the Canaanite period, on the southern foothill, close to the spring of Simiya. This strong spring, a rare source of water in this dry desert area, was a sort of a small oasis. It fed the small fertile valley below it, supporting the villagers with fresh fruit and vegetables.

The major periods were Early Bronze II and III, Middle Bronze I and II, and the Late Bronze period. The findings included structures and possible fortifications of these periods.

A large Necropolis, dated to this period, was discovered on the hillside south of Kh. Samiya. The majority of the tombs were built in shafts, mostly from the Middle Bronze I period (2200-2000 BC). Other tombs are located in 6 burial cluster areas in the vicinity of the site, totaling more than 300 tombs.

-

Iron Age I – Israelite settlement (1200-1000 BC)

During this period the region of the high mountain area witnessed a new wave of settlement, following the conquest of the Land by the Israelites. Dozens of villages were established. According to many scholars, the core of the Israelites settled in the area of Manasseh and Ephraim, and only later expanded to the south (Benjamin and Judea). Therefore, the capital city was selected to be in Ephraim, and only at the end of this period it moved to Jerusalem. Shiloh, located in the region of Ephraim, became the religious capital of Israel: it was the assembly place for the people of Israel, a center of worship, and housed the Ark of Covenant.

The Israelite settlement on the hill of Marjameh, north east of the spring, started in this period.

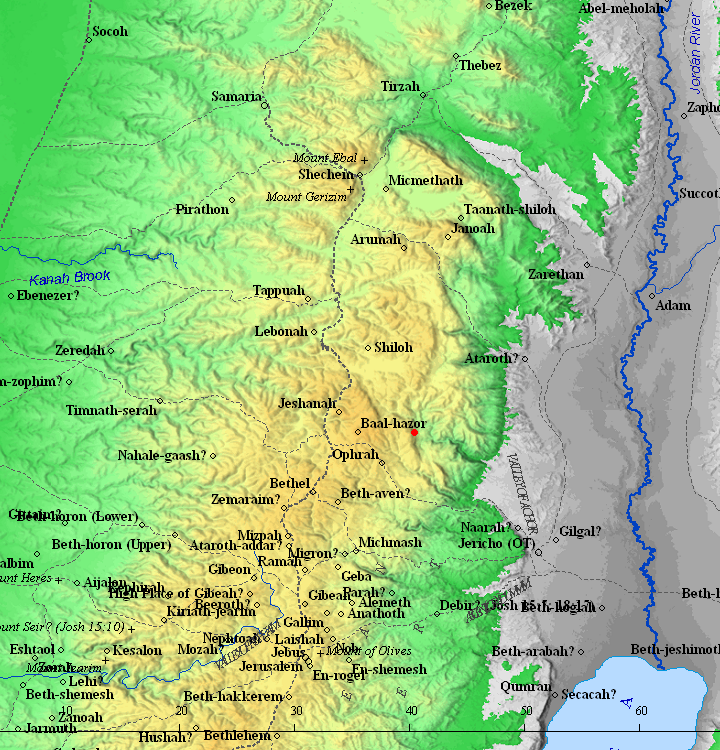

A Biblical map is below, with a red marker indicating the location of the town, at the foothills of Mt. Baal-Hazor and 9km south east of Shiloh.

Map of the area around the site (red dot) – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

-

Iron Age II (925-586 BC)

After the unified Kingdom split (928 BC), the city became part of the Northern Kingdom. According to the archaeological survey, the major period of settlement on the hill north east of the spring of Simiya was in the Israelite period II. The findings on the hill included a city wall, tower, houses and streets.

In 732 BC was an intrusion to the North of Israel by the Assyrian King Tiglath-Pileser III, who annexed the area (as per 2 Kings 15: 29): “In the days of Pekah king of Israel came Tiglathpileser king of Assyria, and took … Galilee…and carried them captive to Assyria”. This intrusion affected the north of the Kingdom, but the area of Samaria was spared since the Assyrians stopped at Megiddo then continued along the shore to Egypt.

Orthostat relief – depicting soldiers from different orders of the Assyrian Army, in procession; basalt; Hadatu Tiglath-Pileser III period (744-727BC) [Istanbul Archaeological museum]

Following the death of Tiglath-Pileser, the Egyptians encouraged the people in the occupied territories of the Assyrians to revolt. Hoshea, King of Northern Israel, joined this mutiny, but made a fatal mistake. This time the Assyrians crushed the remaining territories of the Northern Kingdom. The intrusions of Shalmaneser V and Sargon II in 724-712 ended the Northern Kingdom (2 Kings 17: 5-6): “Then the king of Assyria came up throughout all the land, and went up to Samaria, and besieged it three years. In the ninth year of Hoshea the king of Assyria took Samaria, and carried Israel away into Assyria, and placed them in Halah and in Habor by the river of Gozan, and in the cities of the Medes”.

The villages in Samaria were destroyed, including this city. It was never built again on its old location.

The ruins of the Canaanite and Israelite city, named Kh. Marjameh, are described in another page.

-

Persian, Hellenistic, Hasmonean periods (5th-1st century BC)

It is not known when the town was resettled. The area was under the Samaritans region until it was captured by the Hasmoneans during the mid 2nd century BC.

-

Early Roman period (1st century BC- 2nd century AD)

A kokhim (loculi) type burial complex that was found near the site is typical of Early Roman period Jewish tombs. This implies that the site was inhabited at that time by Jewish settlers.

The village identification was suggested by B. Zissu as Tel Kakhelet [link], a place which is mentioned 5 times in the Qumran copper scroll. According to the scroll, immense treasures were buried in 5 points in Kakhelet during the great revolt (or other times, as suggested by other scholars).

A cave located inside Wadi Samiya, 500m north of the spring, served as a hiding place during the great revolt against the Romans (66-73 AD) and Bar Kochba revolt (132-136 AD). According to the ceramics found in the cave (named “Leopard”), it was also used in other periods as a temporary hiding place for refugees, starting from the Middle Bronze period up to the Mameluke periods.

-

Late Roman and Byzantine Period (2nd century AD -7th century AD)

The major period in the site is the Late Roman and Byzantine period.

On the northern slopes of the mountain, east of Kh. Samiya, is a large ancient Necropolis. Of the 44 burial chambers found and examined, 16 were of this period, with one Israelite period grave and the rest of the Middle Bronze period.

Ruins of a Byzantine church with polychrome mosaic floor was found on the western side of Kh. Marjameh.

Across the valley, southeast of Kh. Samiya, are ruins of a Byzantine monastery (named al-Qasr – Arabic for “the fort” or “the palace”).

-

Ottoman period (19th century)

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine in 1882. They reported on their account of the villages and ruins around the site (SWP, Vol 2, sheet XV). A section of their map appears here.

Part of map Sheet 15 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

According to their report, the village in Kh. Samiya was already ruined, but previously inhabited during the 19th century.

Their account of Kh. Samieh and Ain Samieh appears on page 394:

“Ruined village, with a tower and springs ; appears to have been inhabited within the present century. The ruins occur close to ‘Ain Samieh as marked on the map. There are remains of two mills, and the ruins of foundations, walls and caves, cover a large area. A copious spring issues on the north-west side of the valley from a strongly-built wall forming a tank. A fragment of a column and some drafted stones are built into this wall”.

Another report by Guerin (‘Samaria,’ ii. 211) is quoted by them:

‘The ruin is close to the ‘Ain el Samieh. This spring flows under a chamber with circular vaulting and built of large blocks: near it lie several fragments of columns in stone and capitals imitating the Doric style. To the north and above the spring I remarked the ruins of a considerable building, intended perhaps to protect it, and constructed of gigantic blocks rudely hewn. On the lower slopes of the mountain a great many grottoes have been cut in the rock.’

- Modern Period (20th-21st century)

The ruins of Kh. Simiya were excavated by Baqiza Shantur (1970), Zaydan Wahid (1975) and Omar Hanafsa (1979). The major periods of their findings included Late Roman, Byzantine, Umayyad and Early Ottoman.

The nearby site of Kh. Marjameh, on the hill north east of the spring, was excavated by Amichai Mazar (1975, 1978) and Mattanyahu Zohar (1979-1980). It is reviewed in a separate web page.

Photos:

(a) Aerial views:

A drone captured this view from the north side. The ruins of Kh. Samiya are spread around the modern paved road that leads to the spring.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The ruins above the road are in the following drone view. There are traces of buildings, walls, cisterns and installations covering the area.

The next photo shows the valley to the north and east of the site. The Allon Road crosses the valley from North (left) to south (right).

Ruins of a mill and caves are seen on the left side. The fertile Samiya valley extends to the east, then winds down to the Jordan valley beyond the hills in the far background.

A view towards the north is next. On the left side of the valley is a steep hill, where ruins of a Canaanite and Israelite walled city are seen. This is Kh. Marjameh which will be reviewed in another page.

Also to the north of the site is the spring of Samiya – the source of life in this dry desert area. A modern pump pushes water up the western foothill, providing water to Ramallah and el-Bireh district. The pipe is seen to the left of the large trees.

A closer view of the spring:

![]() The following YouTube video shows a flight of a drone over the site.

The following YouTube video shows a flight of a drone over the site.

(b) Ground views:

The ruins of Kh. Samiya are spread over 30 dunams (3 hectares), at the base of a slope of Mt. Ba’al Hazor, and east of the spring.

The majority of the ruins – buildings made of ashlar stones, rock-cut caves, walls and structures – are dated to the Late Roman and Byzantine period.

According to the archaeologist who studied the site (Kallai, 1972), during the Roman/Byzantine period the settlement descended from the vicinity of the spring (Kh. Marjameh) down and south, along the valley.

Another view of the ruins along the foothill:

The next photo shows the ruins and caves on the north side.

A modern paved road crosses the area of the ruins. It connects the Allon Road to the spring.

One of the main standing structures is located on the side of the road:

(c) Samiya Spring:

The Samiya spring is the reason why the site was settled through thousands of years. The dry desert area cannot support more than few shepherds, while the Canaanite/Israelite city and the Roman/Byzantine town required a steady source of running water.

A closer view of the spring area is in the following photo, where the large trees are seen on the left side. The spring is located at the bottom of the Samiya valley, on the foothill of Mt. Baal Hazor. It flows out of a deep, narrow gorge surrounded by high cliffs. Samiya is the largest spring in the eastern central region of Samaria.

A modern water pump facility fetches the waters, and pushes them up via a pipe to Ramallah and Al-Bireh district.

The station’s daily capacity is 7750 m3, extracted from 5 wells. The deepest well is 750 m (!) deep.

Some of the waters also fill up troughs to supply water for the herds.

A white donkey is one of the animals who enjoy the waters…

(d) Mill:

The Samiya valley passes on the east side of the ancient ruins, as seen in this aerial view. The waters from the spring irrigates the small valley, continuing its flow down hill towards the winding valley that eventually flows to the Jordan river. On the hill above the valley are caves and burial tombs.

Just above the valley are remains of an aqueduct and an arched bridge. These are the ruins of an Ottoman period flour mill.

The power of the spring waters were used to turn the mill crushing stones, in order to crush the wheat grains into flour.

(e) Samiya valley:

To the south of Kh. Samiya, across the Allon Road, is the extension of the valley. This fertile land was used in antiquity for irrigating the fields. The valley is still in use by the farmers. This oasis is in contrast with the dry desert area around the area, which supports only herd grazing in a limited season.

On the foothill above the south east side of the valley, about 1km from Kh. Samiya, are remains of a Byzantine period monastery.

A closer view is seen in the following photo. The ruins include a chapel, rooms and a cistern. The monastery was examined and reported by Hirschfeld. It is named al-Qasr – Arabic for “the fort” or “the palace”.

(f) Necropolis:

A large Necropolis, dated to this period, was discovered on the hillside east of Kh. Simiya. The majority of the tombs were built in shafts, mostly from the Middle Bronze I period (2200-2000 BC).

Of the 44 burial chambers found and examined, 16 were of the Roman/Byzantine period, one tomb was an Israelite period grave, and the rest were shaft graves of the Middle Bronze period.

Other tombs are located in 6 burial cluster areas in the vicinity of the site, totaling more than 300 tombs.

The shafts are seen on the side of the paved road to the spring.

Here, Ofer F. peeks into one of the burial shafts.

Each grave has a vertical shaft, leading down to burial chamber(s) at the bottom of the shaft.

The illustration here shows the cross section of a typical burial complex.

Cross section of a MB shaft tomb

The shaft leads down into a lower section, where burial chambers are cut on the side. The chambers are entered via narrow openings, which are sealed by large blocking stones. The tombs were resting places for single persons or used by the family who owned it.

The dead were buried together with weapons, ceramic lamps and house ware articles, and jewelry.

Other openings:

A Roman/Byzantine rectangular cist tomb is also found here:

A closer look on the cist tomb, with a place for the stone cover.

This was one of the 16 tombs from this period that were found by Yevin (1970) in this area, including a tomb complex with 9 kokhim (loculi). The kokhim type is typical of Early Roman period Jewish tombs, implying that the site was inhabited at that time by Jewish settlers.

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the place:

- Samiya, Samiye, Samiyeh – Arabic: high.

- Ain Samiya – Arabic: Samiya spring.

- Khirbet Marjameh – Arabic: ruin of the heap stones.

- Wady ‘Aujah, or Ujah – Arabic: the crooked valley

Links and References:

* External:

- Identification of the city of the Israelite city near Kh. Samiye, Judea and Samaria researches, 1993 (pp 17-28), Hebrew;

- The Identification of the Copper Scroll’s Kahelet at Ein Samiya in the Samarian Desert – Boaz Zissu, Bar Ilan Univ. , PEQ 133 (2001)

-

Archaeological survey in the Leopard cave – Dvir Raviv et al.

* Biblewalks sites:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- Kh. Marjameh – nearby site (east of the spring)

BibleWalks.com – exploring Ephraim

Kh. Jibeit <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Samaria site—>>> Kh. Marjameh

This page was last updated on Mar 11, 2017 (Added shaft tomb illustration)

Sponsored links: