Ruins of a large Roman and Byzantine village. A cemetery is located on its west side, with many rock-hewn burial caves, cist graves and sarcophagi. Other rock cuttings are located near the ruins.

Home > Sites > Yizreel Valley > Kh. Sahar (Sireh)

Contents:

* General

* Quarry

* Caves

* Misc

Background:

Ruins of a large (500 m2) Roman/Byzantine village on the north-east foothills of Giv’at Hamoreh. A cemetery is located on the hillside above the village, with many rock-hewn burial caves, cist graves and sarcophagi. Other rock cuttings, quarry and agriculture installations, are located near the ruins.

Location:

The access to the site is from the Arab village of Naurah, located 1KM to the east. You can reach it either by foot or by a off-road vehicle.

History:

-

Roman/Byzantine period

The village of Sahar/Sireh was established in the Roman period and existed until the early Arab period. Its ruins are located on a plain east of the foothills of Giv’at Hamoreh, covering an area of 500m2. A road traverses the village from west to east along 50m, which connected it in ancient times to Naim (Nein, 3 KM to the west) and Kh. Elef (Ma’luf, 300m to the east).

The site is famous for its extensive rock cuttings – agriculture installations, a quarry, a large cemetery including burial caves, cist graves and sarcophagi, and a quarry.

The village was destroyed in the Persian or Early Arab period, and is in ruins since then. It was not yet excavated.

-

Crusader and Mameluke

The stone quarry at the foot of the cemetery is probably dated to the Crusader period, when the builders of the fortress of Belvoir cut stones for their construction.

-

Ottoman period

The site was examined in the PEF survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. It appears in the center of the section of this map of 1878 as “Khurbet Sireh” on the east and “Kh. Maluf” on the west.

Part of Map Sheet 9 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

It seems that both sites were swapped in position, since Kh. Sireh (Sahar in Hebrew) is located on the eastern slope of Givat Hamoreh, while Kh. Ma’aluf is located on a saddle east of Giv’at Hamoreh.

-

Modern period

Kh. Sahar was surveyed by Zvi Gal (map of En Dor) as part of the archaeological survey of Israel. A map of the cemetery and ruins is illustrated on page 80.

Plan:

A cross section topographic map of the site, generated from south-west to north-east, is seen in the illustration below. The foothills of Giv’at Hamoreh is on the left (west) side. The burial caves (15) and rock-hewn cist graves (5 ) are cut into the rock either in clusters or in single burial caves (only a few are indicated on the figure). A number of sarcophagi and their covers are scattered on the hillside. Agriculture installations, which include cisterns, oil and wine presses and rock-hewn cup marks, are located on the lower foothill closer to the ruins of the village.

Photos:

(a) General View

There is a great view towards the east. From left to right: the plains of Ramot Issachar; Beit Shean valley in the far background; and Mt Giboa stretching all the way from the center to the right background.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

The ruins of the village are scattered on the east side of the foothills. During the hours of the sunset, it was difficult to see traces of the structures. The surveyors did identify the bases of walls, houses and even a public building with two rows of columns (church?). They concluded that the structures have been constructed in two or three building phases.

(b) Quarry

An ancient stone quarry covers parts of the foothills. The quarry is dated to the Roman period, as well to the Crusader-Mameluke period.

Rock-cutting was one of the sources of income in the Holy Land at these times. As per the Bible (2 Chronicles 34:11: “Even to the artificers and builders gave they it, to buy hewn stone, and timber for couplings, and to floor the houses”.

The construction of buildings and structures switched from mud (Canaanite period – Bronze Age), to un-hewn stones (Israelite period – Iron age) and then to fine cut stones (Hellenistic and Roman period). The growing demand for hewn building blocks created thousands of small stone quarries such as the one around Kh. Sahar. The Roman period rock cuttings may have been one of the reasons why the village was established at this location.

The Crusader-Mameluke period cutting occurred when the quarry of Kh. Sahar served the stonemasons of the nearby Crusader fortress at Belvoir. Other quarries that served the construction of the fortress exist in other areas around Giv’at Hamoreh, such as in Nein (Naim).

(c) Sarcophagi

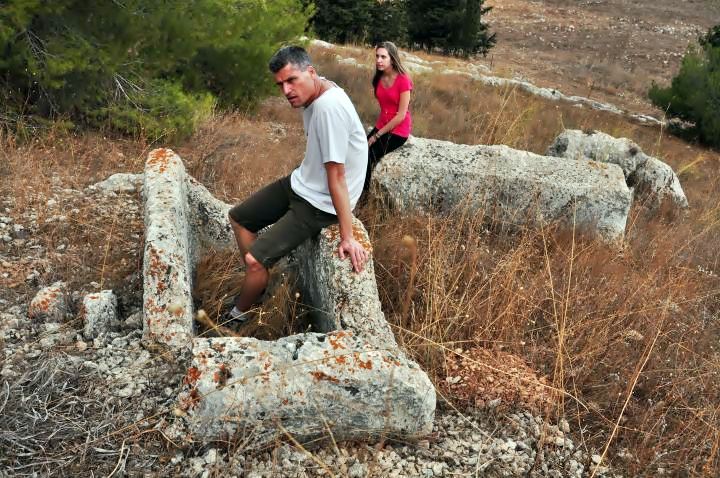

There are several stone coffins scattered on the hillside, as part of the cemetery. In the picture below, Uncle Ronnie examines the lid of the coffin, which rests on its fragmented base.

A sarcophagus (sarcophagi in plural) – in Greek – means “flesh eater”. It is a stone coffin, intended to be a multiple use box that contained the body of the deceased for the first phase. After the flesh decomposed the bones were removed to a smaller container or pit, allowing the next member in the family to be placed in the coffin.

Another sarcophagus:

Other complete and fragmented sarcophagi lie on the slope of the mountain:

View of this sarcophagi with Amit – towards the plains known as Ramoth-Naphtali.

(d) Burial Caves

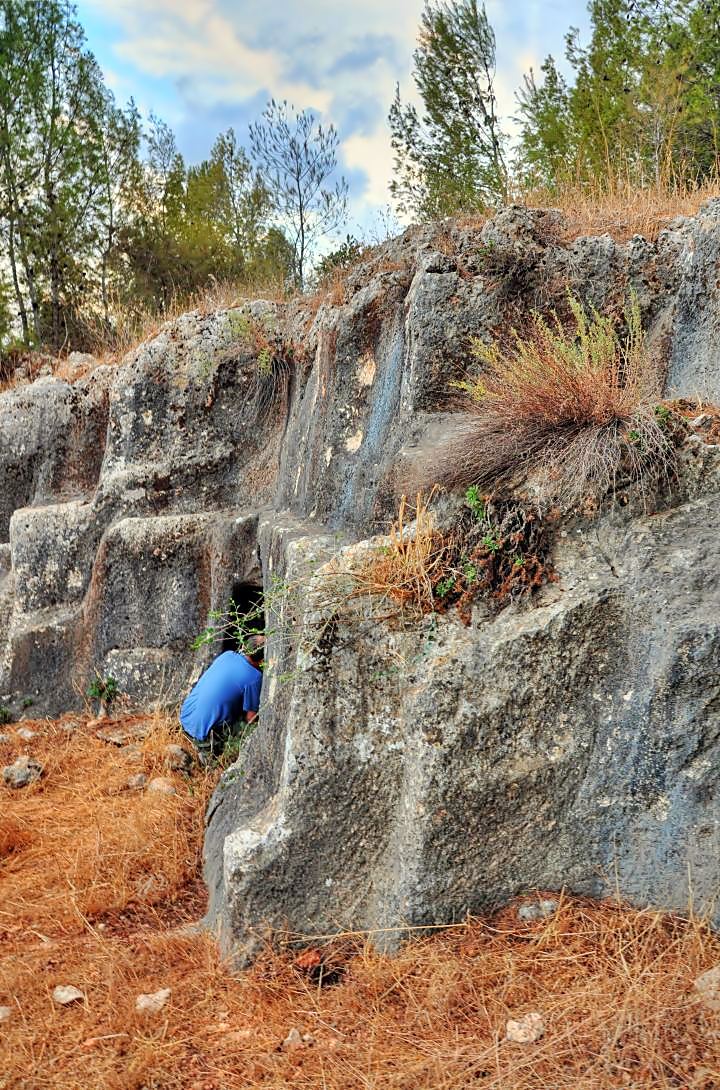

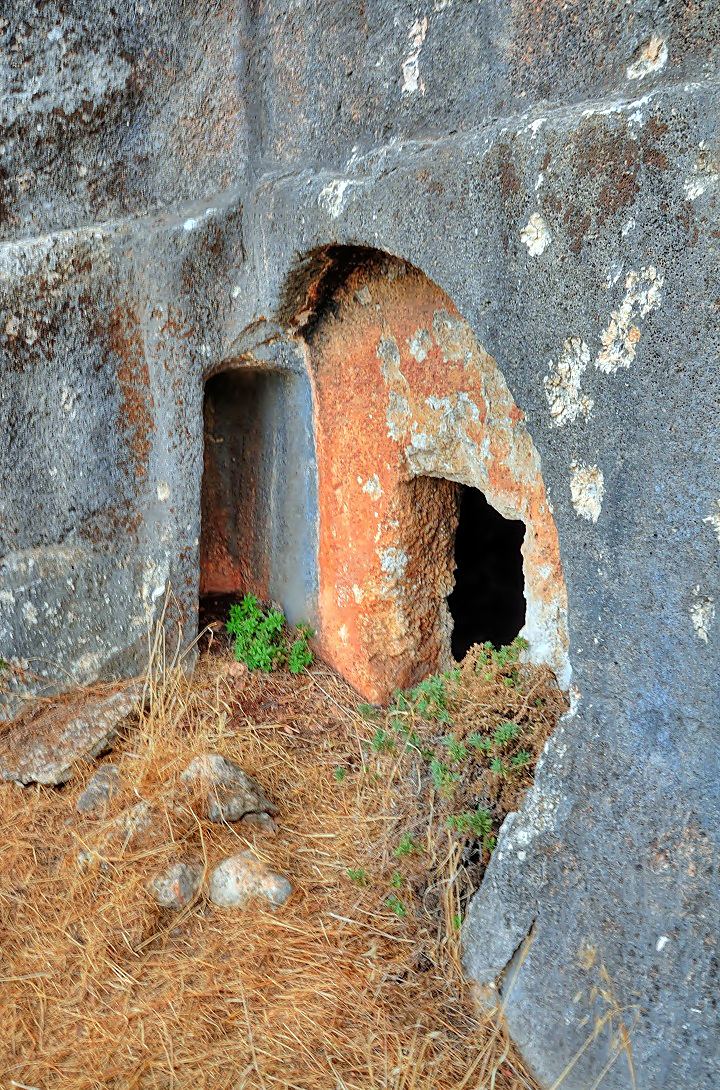

The cemetery includes about 15 burial rock-hewn caves. An arched entrance in front of the cave used to be covered by a large stone door.

Ronnie peeks into another cave in the next photograph.

This practice of burial caves was known from early Biblical accounts, such as the cave of the Patriarchs. Genesis 23 19-20: “Abraham buried Sarah his wife in the cave of the field of Machpelah before Mamre: the same is Hebron in the land of Canaan. And the field, and the cave that is therein, were made sure unto Abraham for a possession of a burying place by the sons of Heth”.

The practice of burial caves tombs increased during the Hellenistic and Roman/Byzantine periods. There are thousands of such caves from these periods all over the land.

A side groove, which is seen on the left side of the entrance, is a common method to hold a blocking stone, which is now missing. A heavy, round rolling stone was normally used as a blocking stone, and was rolled away during burial, then returned back into the groove in order to seal the tomb. As per the Bible (Matthew 28 1-2: “In the end of the Sabbath, as it began to dawn toward the first day of the week, came Mary Magdalene and the other Mary to see the sepulchre. And, behold, there was a great earthquake: for the angel of the Lord descended from heaven, and came and rolled back the stone from the door, and sat upon it”.

Another cave is seen in the next photograph. Uncle Ofer points to holes on the surface above the entrance, where he suspects that someone shot bullets into the rock which pierced the skin of the rock.

Inside the caves are triple burial chambers (“Kuchim”, or “burial recesses”). These stone benches held the corpses until the next burial of a member of the family who owned the cave. The custom of family-owned caves was common, and the Bible told about the practice in several verses: (Judges 8 32): “And Gideon the son of Joash died in a good old age, and was buried in the sepulchre of Joash his father”; (2 Samuel 2:32): “And they took up Asahel, and buried him in the sepulchre of his father, which was in Bethlehem”; (2 Samuel 17 23): “and died, and was buried in the sepulchre of his father.”.

This practice of using a “cold bed” was termed in the Bible as “gathered to his people”. Examples: (Genesis 25 8): “Abraham … died in a good old age, an old man, and full of years; and was gathered to his people”; (Genesis 49 33): “Jacob had made an end of commanding his sons, he gathered up his feet into the bed, and yielded up the ghost, and was gathered unto his people”.

Another cave seem to have been a recent residence of a loner or shepherd who lived here for some time, judging from the rubbish in front of the entrance.

The chambers of this cave are seen below.

(e) Cist Graves

In the cemetery are other forms of rock-hewn tombs called cist-graves. Cist (from Greek “kist”) refers to a small stone-built coffin-like ossuary (box) which is used to hold bodies of the dead. There are 7 such rock-hewn graves in this site.

Uncles Ron and Ofer examine another cist grave on the hillside, which is cut into the rock.

A closer view of this cist grave is in the photo below. The stone lid, which once covered the tomb, is missing – but its fitting grooves are seen on the side of the cavity.

Cist graves were not common in the Biblical period. The majority of Israelites were buried in simple, shallow graves, with or without a heap of stones. The Bible does report on some prominent people who were buried in a box, such as Joseph (Genesis 50 26: “So Joseph died, being an hundred and ten years old: and they embalmed him, and he was put in a coffin in Egypt”). This practice started at a later date, and was common in the Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Yet another such tomb:

(f) Agriculture Installations

On the bottom side of the hill there are several agriculture installations, which include winepresses, an oil press, bell shaped cisterns, two reservoirs with a rectangular shape, rock hewn cup marks and shallow shallow plastered pools.

(g) Misc

It was already pretty dark when we departed from this lovely site, and the winter clouds added an additional blanket of darkness. However, we promised to come back again to visit the site, and explore other parts of it.

References and Links:

* Archaeological:

-

Arch. Survey of Israel – Ein Dor Map (#34) – Zvi Gal [1998] pp78-80, which includes a map of the site.

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the site:

-

Kh. Sahar – the modern Hebrew name, meaning: crescent

-

Me’arot Sahar – Hebrew: Caves of Sahar – referring to the burial caves

-

Kh. Sireh – name in the Survey of Western Palestine

-

Mughr es Saghira – name in the British Mandate maps

BibleWalks.com – walk with us through the sites of the Holy Land

Naim<<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>—next Yizreel/BeitShean Valley site—>>>Ein Dor

This page was last updated on Nov 3, 2010

Sponsored links: