St. George Koziba is a cliff hanging Byzantine monastery in the valley of Wadi Qelt, near Jericho.

1 Kings 19:9: “And he came thither unto a cave, and lodged there…”.

* Site of the Month Oct 2015 *

Home > Sites > Judea> Desert > St. George Koziba, Wadi Qelt

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

* St. George

* Valley

* Courtyard

* Main Church

* Cave Church

* Hermits

* To Jericho

* Kypros

Biblical

Links

Etymology

Background:

St. George Koziba is a Christian monastery located in the Wadi Qelt (Nahal Prat), a valley in the Judean Desert in the West Bank, near Jericho. The monastery is dedicated to Saint George, who is one of the most revered saints in Christianity.

The monastery was founded in the 5th century AD by Saint John of Thebes, who is also known as Saint John the Hesychast. Saint John was a hermit who lived in a nearby cave before founding the monastery. The monastery was built on the site where Saint George is believed to have taken refuge from persecution during the early Christian period.

The monastery has a unique location and architecture, as it is built into the side of a cliff overlooking the Wadi Qelt. The monastery has been destroyed and rebuilt several times throughout history, with the most recent restoration taking place in the 19th century.

The St. George Koziba Monastery is still an active monastery today and is home to a small community of Greek Orthodox monks. The monastery is open to visitors, who can explore its chapels, monks’ cells, and gardens, as well as enjoy the stunning views of the surrounding desert landscape.

Location:

An aerial map of the lower Wadi Qelt is shown here. The brook flows eastwards into the Jordan river, south east of Jericho. The monastery of St. George Koziba is located on the north side of the brook, at a height of -69m, about 9km away from Jericho.

History:

-

Biblical periods – Early Canaanite to Israelite periods (3150 BC- 586 BC)

A red square on the Biblical map shows the location of the eastern edge of the Wadi Qelt valley on the Biblical map, where the monastery is located.

An ancient route, named the Ascent of Adummim, connected the cities and villages on the mountains of Judea, such as Jerusalem, to the Jordan valley and the city of Jericho. The route was parallel to the course of the valley, and enters into the valley only at its edge.

Area of Jericho – during the Biblical to the Roman periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

According to the tradition, the caves of Wadi Qelt were the place where Elijah stayed during the drought (1 Kings 17 1-7):

“And Elijah the Tishbite, who was of the inhabitants of Gilead, said unto Ahab, As the LORD God of Israel liveth, before whom I stand, there shall not be dew nor rain these years, but according to my word. And the word of the LORD came unto him, saying, Get thee hence, and turn thee eastward, and hide thyself by the brook Cherith, that is before Jordan. And it shall be, that thou shalt drink of the brook; and I have commanded the ravens to feed thee there.

So he went and did according unto the word of the LORD: for he went and dwelt by the brook Cherith, that is before Jordan. And the ravens brought him bread and flesh in the morning, and bread and flesh in the evening; and he drank of the brook. And it came to pass after a while, that the brook dried up, because there had been no rain in the land”.

The desert dwelling is repeated in 1 Kings 19, when Elijah hid in a cave fleeing from the anger of Queen Jezebel.

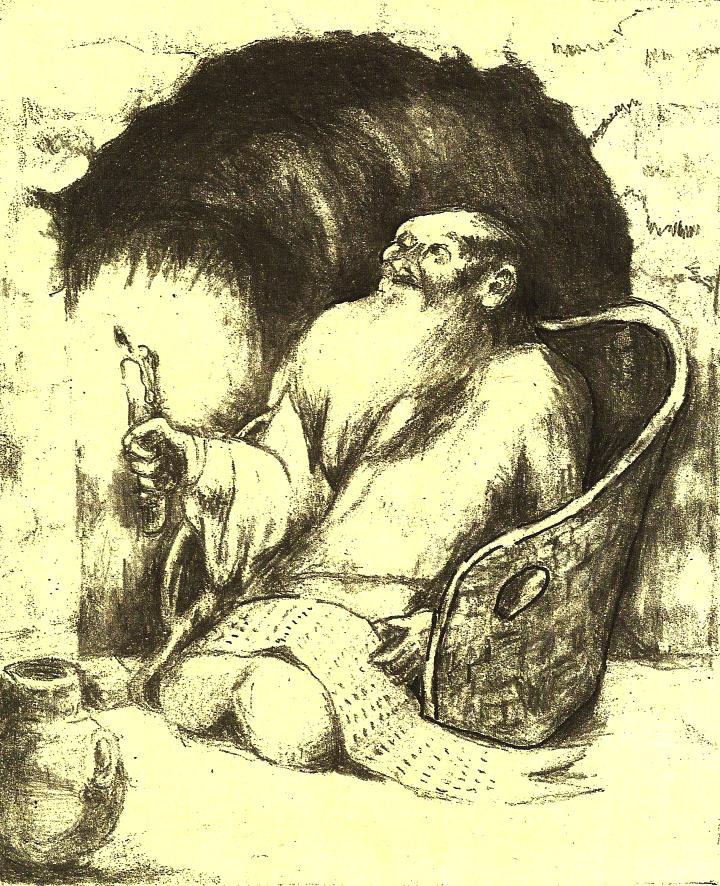

Elijah in the desert, fed by ravels

[Painting in St. George Koziba monastery]

-

Byzantine period (4th-7th Century AD)

Starting from the 4th Century, monks started to populate small caves along the banks of Wadi Qelt. Many such monks found the desert as the suitable place of seclusion, following the ‘Desert theology’ of the Old Testament, where the Israelites wandered for forty years in the desert in order to change their nature and heart. They also were following the footsteps and life-style of Jesus , who secluded to the desert for forty days in order to prove his obedience to God (Matthew 4:1-11, Mark 1:12-13, Luke 4:1-13) , as well as Elijah the prophet and John the Baptist. The desert monks are often called ‘Hermits‘, based on the Latin and Greek words ‘eremita’ and ‘eremites’ (means: “of the desert”).

Christian Monasticism is a religious way of life, where the person denounces worldly pursuits and fully devotes one’s self to spiritual work under religious vows. The word originates from Greek, based on the act of ‘dwelling alone’ (monos). The monks, a word derived from Monasticism, lived in seclusion from the World in places called monasteries (also derived from monos). They withdrew from society and devoted themselves to the purpose of spiritual renewal and return to God.

During the Byzantine period (4th-7th century AD) the hermits found the Judean desert a place of choice for seclusion in the Holy Land.

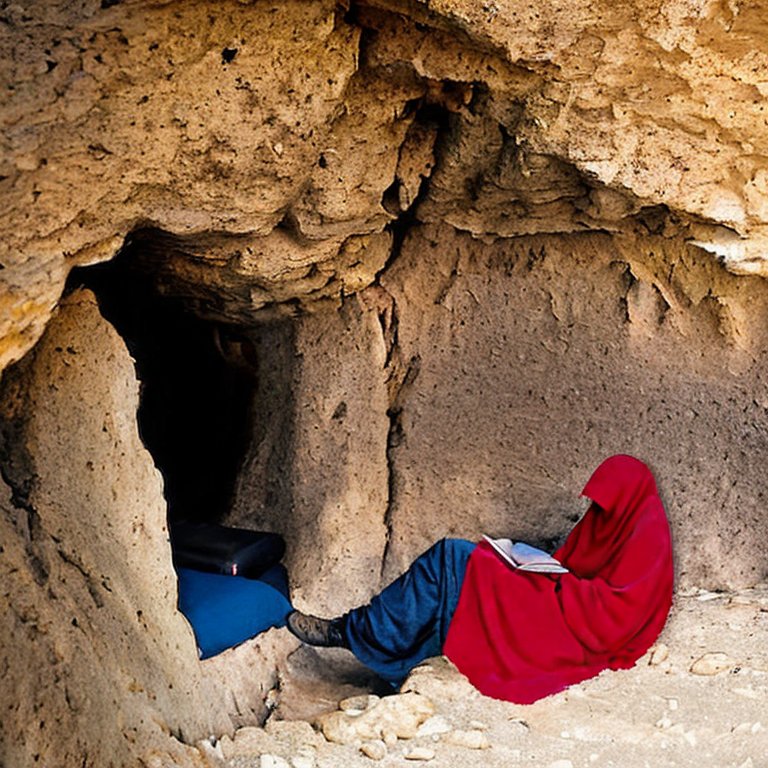

Secluding monk

This way of life formulized into two common methods of Judean desert monasticism – the Laura and the Coenobium. Initially these forms were loosely formulated, but in time the oral tradition became more disciplined and followed strict written rules.

The monastery of Wadi Qelt started as a Laura. The Laura (or Lavra) originally meant a cluster of caves or cells used by the hermits for seclusion, with a church as their weekly meeting center (usually on Sundays). This functioned as a monastery for hermits, with an emphasis of solitary religious living during the 6 weekdays. The word is derived from Greek (meaning “a path”).

Illustration of hermit in a cave – AI generated by Stable Diffusion

St. John of Thebes (5th-6th Century):

The monastery was founded in 480 AD by John of Thebes (city in Egypt). John was born in Egypt in 440-450, and came to the Judean caves for seclusion. He gathered several several monks from the nearby caves into a new Laura.

In 516 AD John was appointed the Bishop of Caesarea, but later returned to the Laura.

St. George (6th-7th Century):

George came from Cyprus as a young person in the end of the 6th Century and became a hermit in the caves of Wadi Qelt. During the Persian conquest in 614 the monastery was destroyed, and 40 of its monks were murdered. George was imprisoned but survived, and kept to dwell in the ruins of the Monastery until his death in 620. He was honored by the monks who named the Monastery as St. George Koziba.

Hozebith, also spelled Chozeboth or Koziba, is based on the Hebrew name “Hazeva” meaning digging-in (Poverbs 9,1): “Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars”. Indeed, the monastery digs into and hangs in the cliff above the valley.

St. George the Hozebith

-

Crusaders

The ruined monastery was restored in 1179 by the Byzantine King Manuel I Komnenus (1118-1180). Manuel, who reigned from 1143, was an influential Byzantine emperor during the second Crusade. King Manuel I was a patron of many constructions in the Holy Land, such as the church of nativity in Bethlehem.

-

Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

The monastery was damaged after the defeat of the Crusaders, and remained in ruins until the end of the 19th Century.

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. It appears on the map of sheet 18 and described in Volume III.

A section of the map, showing the lower section of Wadi Qelt (Kelt), is below. The monastery is marked as “Deir el Kelt” on the middle left side.

A Roman road (“Ascent of Adummim”) is marked as a double-dashed line. It starts in Jericho on the right side, passes along an eastern section of the valley, then goes in parallel to the valley en route to Jerusalem.

Their comprehensive description on pages 192-198 describes the state of the monastery before it was repaired:

“Deir el Kelt – A ruined monastery perched in the side of a perpendicular precipice on the north bank of Wady Kelt. It is approached from the east, on which side is a narrow plateau (120 feet east and west, 30 feet broad) having above it a cliff. For over 80 feet in length this cliff is covered with cement, which was once painted in fresco, with figures now obliterated. In the cliff above the monastery are caves, now inaccessible. In one an iron bar was visible, probably once used for fixing a rope or rope-ladder, by which a communication with the hermit in the cell might be effected”.

Part of map sheet 18 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Their report of 1873 continues, describing the ruins of the monastery:

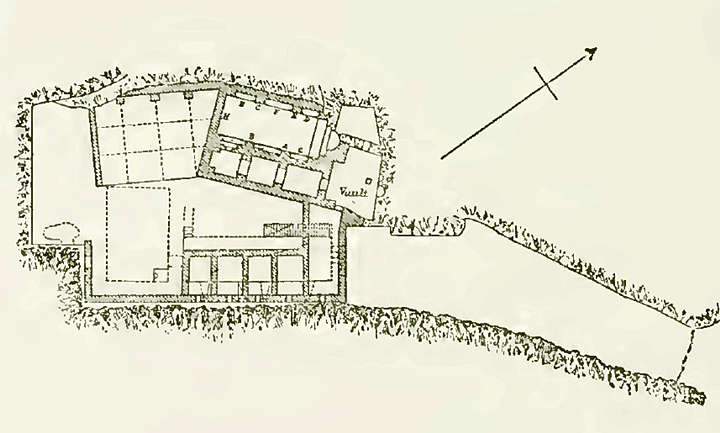

“The monastery itself shows three distinct dates of building. The edifice includes an entrance-hall with vaults below, a chapel and cells. The chapel is not in the same axis with the rest of the buildings, and appears to be earlier. The masonry in it is better dressed than in the rest of the work. The chapel is 36 feet long by 17 feet broad, interior measure. Its bearing is 45°. At the east end is an apse 7 feet diameter ; this has a window in the side placed askew, so as to have a bearing 90°, or due east. Behind the chapel Is a small chamber having a tomb beneath the floor, cut in the rock, and containing remains of bones much decayed. This chamber has also an apse. The small cell beyond this is cut in rock, and measures 10 feet by 13 feet. A corridor leads from the south door of the main chapel to the smaller chapel. The buttresses in the large chapel are evidently later additions, for they are built across the second series of frescoes ; they support the ribs of the vault, and they are of finely dressed ashlar. The interior walls of the chapel, of the corridor, and of the small chapel behind, are all covered with cement and painted in fresco, with figures and inscriptions. Two sets of these frescoes are visible in places ; the older are much defaced, but appear to have been better executed….”.

A plan of the monastery is illustrated on page 192, with a legend of the inscriptions and frescoes that the survey identified, as detailed in the remainder of their report.

Illustration of the monastery [PEF report, Vol 3 p. 192]

The surveyors concluded (pp 197-198):

“We have thus indications of the various dates of the buildings :

* 1St. The chapel and the original frescoes, dating possibly back to the early Christian period (fifth century).

* 2nd. The monastery, the vaults, and the second series of frescoes. Probably Crusading, from evidence of the character employed in the inscriptions.

* 3rd. The restoration of Ibrahim and Musa of the town of Jufna, which is still a Christian village”.

Starting from 1878, just a few years after the survey, a Greek monk by the name Kalinik started to restore the monastery, which was completed in 1901.

-

Modern period

St. George Koziba is one of the few monasteries which are active in the Judean desert. Since the site is close to hostile areas, it is advised to follow security instructions regarding the visit, and always travel in groups.

Photos:

All photos by Tuvia Liran

(a) St George:

The cliff hanging structures of the monastery are located on the north bank. A bridge – seen on the bottom of the picture – connects the south and north sides of the Qelt valley.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

A closer view of the monastery is seen in the following photo.

The monastery has several levels of construction:

- On the lowest level are storehouses and a vault where the remains of the early monks are kept.

- On the middle level is the main church.

- On the upper level is the cave of Elijah.

(b) The valley:

The Qelt valley to the south of the monastery is fertile, and served the monks to grow some vegetables and operate a nearby flour mill.

The waters were conveyed by an aqueduct from the Qelt spring, 3KM upstream.

(c) Monastery Courtyard:

Tuvia, whose photos appear in this web page, stands at the entrance to the monastery. An inscription is seen on the wall to the left of the entrance.

Inside the courtyard of the monastery:

A bell tower was added in 1952:

A closer view of the bells:

(d) Main Church:

The main church was initially dedicated by the founder St. John to the Virgin Mary. It was later dedicated to St. George the Hozebite and St. John Jacob the Romanian.

The painted ceiling of the main church is seen in the following photo:

The “Templon”, also called the iconostasis, is a decorated covered screen with icons and paintings. It separates the hall of the nave and the altar behind the center table. The middle door, called the beautiful gate, is used only by the clergy to enter to the altar behind the templon. In its center are the golden royal doors.

The double headed eagle is a symbol of the Byzantine empire and the Greek Orthodox church, such as seen on the floor of the Holy Sepulcher.

Inside the chest is the box, or reliquary (container for relics), are bones of St. George the Hozebite, a famous hermit who dwelt here in the 6th Century and gave the name to the Monastery.

In the church are relics of the founding fathers, and remains of the monks who were killed here in 614 AD during by the Persians.

On the wall, among other paintings, is the illustration of St. George the Hozebit.

The following photo shows a detail of the previous picture. Inside the glass gasket are remains of a Romanian monk, St. John Jacob the Romanian, who dwelt here in a small cave for 8 years and died in 1960.

Other sections of the church are shown in the next photos:

Another section, behind the door:

An illustration shows (top row): Jesus in the center, Mary on the left, and Joseph on the right. On the right side are the founding monks, and on the lower left side is the scene of the death of Virgin Mary.

(e) Cave Church:

The small cave-chapel behind the main chapel is in the following photo. This is the cave church of St Elijah. The walls are also covered with frescoes, with figures and inscriptions. On the left side of the fresco is Elijah in a cave in the desert, fed by the raven.

A painting of Elijah in the desert is seen in the next photo. The Greek letters on the right are Ηλίας, or: Elias (Elijah).

The prophet is often illustrated with a raven bringing food while he was hiding, as described by the Bible (1 Kings 17: 1-7): “…Get thee hence, and turn thee eastward, and hide thyself by the brook Cherith, that is before Jordan. .. And the ravens brought him bread and flesh in the morning, and bread and flesh in the evening; and he drank of the brook”.

The Cherith brook in this passage, according to the Byzantine tradition, is Wadi Qelt (an Arabic name of the valley). The Biblical name of the brook “Cherith” may have meaning “engraving”. Perhaps that is the source of the Byzantine name of the place – Hazeva (meaning in Hebrew digging in).

(f) Monks:

The monks, or hermits, lived in seclusion in caves around the monastery. There are dozens of such caves located along the valley, especially on the north bank, east of the monastery.

Another section of valley, with openings to small caves where the monks once used to seclude themselves:

Some of the caves had walls built inside, such as the cave seen here on the north bank:

Another cave with built staircase:

The following cave is reached within the complex and is reached by a ladder. The food and water were raised up to the monk by a lever and basket.

A small chapel is also built nearby, in the entrance to one of the caves.

(g) Down to Jericho:

Along the south bank of Wadi Qelt is the route of the Roman road from Jericho to Jerusalem.

In a level below the road is the Ottoman period aqueduct, which brought water from the springs of Qelt down to the agriculture fields of Jericho.

The tour continued down to the eastern edge of the valley, along its northern bank. This path follows the course of the second (earlier) aqueduct, dated to the Hasmonean period (2nd Century BC). It brought waters from the Qelt spring down to the Hasmonean palaces.

Some panoramic scenes along the walk are in the following photos:

Black crosses marked the way to the monastery.

A station along the way, with steps around the cross, seemed like a good place to rest:

Getting closer to the plains of Jericho and the Jordan valley, the first houses appear in the background:

The edge of the valley is reached. Notice the Ottoman period aqueduct on the top right side, at a higher level, which brought water to the city of Jericho.

The neighborhoods of modern Jericho, in the western side of the Jordan valley, are seen in the background of the following photo.

In an area closer to the edge of the Wadi Qelt are remains of the Hasmonean palaces of Jericho, as well as ruins of Roman Jericho. These are described in a separate page.

Farther on its way to the Jordan river, 10KM to the east, the brook cuts through the soft layers of the Marlstone, a soft rock (Hebrew: Havar), which is made of calcium carbonate or lime-rich mud. The marlstone is a residue of the deposits accumulated when the Dead Sea covered larger areas, starting from 2 Million years ago.

(h) Kypros fortress:

South of the edge of the valley are the ruins of Kypros (Cyprus), a desert fortress built by the Hasmoneans. The fortress was one of two Hasmonean desert forts (named Threx and Taurus) that sealed the north and south sides of the entrance to Wadi Qelt – an important route to Jerusalem.

Kypros was first built during the Hasmonean Kingdom, probably in 120BC by John Hyrcanus (reigned 134-104BC). Josephus Flavius wrote (Wars 1 8 2): “He (Hyrcanus) also built walls about proper places… that lay upon the mountains of Arabia”. The purpose of this fortress, as well as the other six desert fortresses, was to protect the eastern border of the Jewish Kingdom against the Edomites and other threats from the east. These fortresses had additional designations – they served as palaces, protected royal treasures, stored supplies and weapons, and also functioned as prisons.

The fortress was probably destroyed by Pompey the Great during the Roman conquest in 63 BC. It was later refortified by Herod the Great, and named after his mother.

Links:

* External links:

- The Holy Monastery of Saint George of Hazeva and St. John Jacob the Hodzebite

- Tagliot – “Archaeology for All” (Hebrew site) – arranged the tour, which was guided by guided by Dvir Raviv.

* Internal links:

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the valley/brook:

- Wadi, Vadi – Arabic: valley

- Wadi Qelt (Kelt) – Arabic name of the valley, meaning hallow mountain or tarn (mountain pool).

- Wadi Pharah (Farah) – Arabic: the valley of the mouse.

- Perath brook – Also Euphrates, which is the large river in Mesopotamia. In Jeremiah this was one of the valleys out of Jerusalem. The name was given to the Wadi Pharah. 13:3-9 (4: “…arise, go to Euphrates, and hide it there in a hole of the rock).

- Hazeva – The word is based on the Hebrew root for drill, and appears in the Bible meaning “hewn” (Poverbs 9,1): “Wisdom hath builded her house, she hath hewn out her seven pillars”.

BibleWalks.com – walks along the Jordan river

Kesalon<<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next Judea site—>>> Maresha

This page was last updated on Mar 16, 2023 (new overview)

Sponsored Links: