In Tel Gezer are ruins of a major Canaanite and Israelite fortified city. It was one of the famous Biblical cities, conquered by Joshua and fortified by King Solomon.

Home > Sites > Shefela > Tel Gezer

Contents:

Background

Location

History

Structure

Photos

* Aerial views

* Access

* Canaanite city

* Israelite City

* High Place

* Sheikh’s tomb

Special Findings

* Gezer tablet

* Gezer boundary Rocks

Misc

Etymology

Links

Background:

Tel Gezer is an archaeological site located in central Israel, about 20 miles (30 km) west of Jerusalem. It is an ancient city that dates back to the Bronze Age, and was inhabited by various civilizations throughout its history, including the Canaanites, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, and Romans.

Excavations at Tel Gezer have revealed important discoveries, including the remains of a Canaanite city with a massive stone gate and fortifications, as well as a complex system of water tunnels and a palace from the time of King Solomon. 1 Kings 9-15: “King Solomon raised… the wall of Gezer.” This was one of the first places to be positively identified by inscriptions of the name of the city on rocks around the site. The city was also an important center of worship, with evidence of a temple complex dedicated to various gods, including the Canaanite deity Baal.

In addition to its historical significance, Tel Gezer is also mentioned several times in the Bible, including in the Book of Joshua, where it is described as a city that was given to the Levites as part of their inheritance. The site is open to visitors and offers guided tours, as well as a museum displaying some of the artifacts that have been excavated from the site.

Location:

This aerial map shows the major points of interest in Tel Gezer. The site is located south of the Ayalon valley, in the lowlands of Judea.

You can drive to the parking place by a dirt road from Karmei Yosef.

History:

Macalister, who headed the first major excavation of the city, summarized the history of Gezer in his 1912 report (Volume 1, pp 5-44). We bring here his fascinating report, partially edited:

“The Hebrew root which has the same consonants as the name of Gezer implies some such meaning as “dividing, separating”; and perhaps includes the sense of “precipice.” Though no longer applicable to the site, this latter signification would well fit in with its actual appearance in ancient times along a certain section of the north side ; here the excavation showed that the wall had been built on the edge of a lofty cliff, now completely concealed under detritus. But in Palestine, as elsewhere, the study of place-names is full of pitfalls. It is not unlikely that the etymology of the name is to be sought elsewhere ; it is indeed not impossible that its Semitic appearance may be merely superficial, and that it is a legacy from the aborigines. But such a suggestion would open a maze of conjecture into which we must not venture here. It will be sufficient to take the name of the city as we find it, recording in passing its most obvious derivation”.

-

Pre-Semitic History

“There is no evidence of an occupation of the hill of Gezer itself before the Neolithic period. In the fields around, especially to the northwest and north, stone axes of the Chellean type, the most frequently represented among the Paleolithic remains of Palestine, are to be found, especially after the soil has been turned up by the plough. It is true that a few Paleolithic implements were found here and there in the city ; but these must have been picked up and imported into its precincts in comparatively recent times.

It cannot have been much later than 3000 B.C. when the primitive race which in these pages we shall call the Troglodytes took possession of the caves that abound in the rocky core of the hill. Who these people may have been, and what their relation was to the other tribes of the Mediterranean basin, are questions that for the present must await further researches in other centers of their occupation. The fact that in the principal deposit of their remains discovered, the bones were burnt, and so made useless for minute examination, prevents our obtaining detailed information on their physical character… Let it suffice here to say that they were a small-statured race, in the Neolithic stage of culture, and that they lived in caves and supported themselves principally by hunting or by their cattle”.

- The Early Semites and the Influence of Egypt

“It was not till the first invasion of the Semites that Gezer ceased to be a mere settlement of savages and began to assume the dimensions and the importance of an organized city. Various lines of argument agree in indicating 2500 B.C. as approximately the date of this momentous event; but much of the evidence comes directly or indirectly from Egypt, and unfortunately this is for the present rendered ambiguous by the disagreements among scholars regarding the chronology of the Egyptian Middle Empire.

Egypt very soon began to interfere in Syrian politics, and our earliest literary sources for the history of Gezer come for the greater part from Egyptian soil, and even when found in the city itself are written in Egyptian hieroglyphics.

It is not easy to say whether the imposing engineering works that are a notable feature of the early Semitic city – especially the inner city wall and the great tunnel – are native works or were constructed under the influence of a dominating external civilization. On the whole the latter is the more probable, though the regrettable absence of epigraphic evidence leaves the question open. It is not easy to imagine the superior sheikh who called himself “King of Gezer ” conceiving and executing the design for the tunnel uninfluenced by some pressure from without. It is true that Egypt has not yet produced a monument of the Middle Empire in which the name of Gezer has been recognized. But the excavation yielded evidence that trade between the city and the empire of the Nile was actively carried on, especially under Senwosret (Sesostris) I and during the Hyksos dynasty ; and that a number of Egyptians were actually resident within the city walls. It is highly probable that the Egyptian suzerainty, which is a well-established historical fact of a later century, actually began at a date earlier than that for which we have direct epigraphic evidence.”

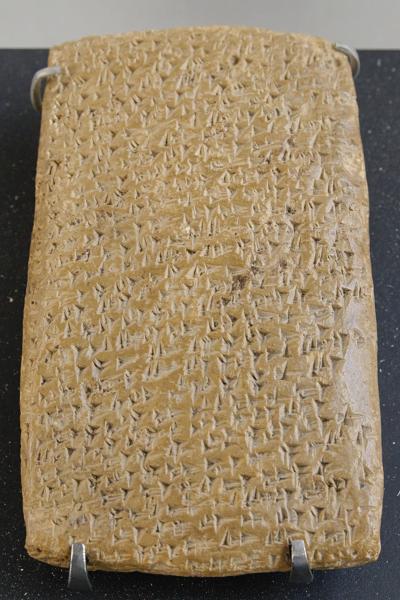

“Thutmose III transmitted the dominion of Palestine to his descendants ; but till we reach Amenhotep III, we learn nothing about Gezer from the monuments. This silence, however, is compensated for by the great hoard of letters belonging to his reign and to that of his successor Amenhotep IV (Ikhnaton) found in 1888 at Tell el-Amarna.

In these tablets, unfortunately for us, much valuable space is wasted in empty compliments to the Pharaoh and in Chinese-like protestations of abasement : the meager remainder being about equally divided between not very convincing disclaimers of charges of disloyalty brought by rivals against the writers, and similar counter-charges (obviously inspired by personal malice) against most of the writers’ neighbors. However, in all this wilderness of envy, hatred, and uncharitableness there is a precious harvest to be gleaned. The numerous references to Gezer are of special Interest in the present discussion. The letters trace the gradual defection of Syria and Palestine from Egypt, and the failure of the governors of the different cities to stand against the growing power of the Aramaean tribes. Ikhnaton, the first great religious fanatic of history, had no leisure to think of temporal matters. While he was busy developing his theories of cult and of art his great Asiatic dominion gradually crumbled away, and we can watch the disintegration in progress with the help of these very human documents”.

One of Tell Amarna letters (Louvre Museum, Public domain CC 2.5)

Cuneiform writing on a clay tablet.

In the Macalister report are details of the letters that relate to Gezer. The history summary continues:

“Two other references to the city are to be found in a monument on Egyptian soil. The first is on the stele of Merneptah, famous for its enigmatical reference to Israel. The passage containing the name of Gezer runs as follows :

“The Libyans are destroyed : the Kheta are at peace : the land of Canaan is captive . . . : Ashkelon is carried into captivity : Gezer, too, is taken : Yenoam is destroyed : Israel is spoiled, it has no crops : Southern Palestine is like a widow for Egypt”.

“So far as the results of the excavation permitted us to judge, very few traces of these events remained in the city itself. Scarabs of Thutmose III and of the Amenhoteps were fairly common, and these and other small Egyptian objects shewed that there was intercourse between the city and Egypt under those monarchs. But Beia, Yapahi, Labaya, and the rest have vanished from the scenes of their activities and left not the smallest recognizable trace”.

“That Merneptah’s claim to have conquered Gezer is not (as it might be regarded with tolerable probability) a mere empty boast, is indicated by his assumption of the special title “Binder of Gezer ” in the second of the passages referred to an inscription in the temple of Amada. We may perhaps see a monument of his conquest in an ivory pectoral [IV 10] that bears his cartouches. On the face is a figure of the king adoring the god Thoth ; on the reverse is a group of radiating lines. The straight side is 2 1/4″ long. The ivory having shrunk a little, the circles – originally no doubt struck with a compass from the small dot in the centre above the discs with uraei – have become flattened. The broader parts of the cutting retain the green enamel with which they were filled. This object was the only relic of Merneptah found in the city. Thus the Egyptian records regarding Gezer close, as 250 years before they opened, with the bare mention of its capture by the Pharaoh”.

Merneptah’s Israel stele in Egyptian Museum

in Cairo (Wescribe; license CC3.0)

- The Hebrew Invasion and the Old Testament References

The next chapter is the “Hebrew invasion”, as the author calls this period, referring to the Iron Age. A map of the cities and roads of the Old Testament period is added here, with Gezer marked as a red point.

The cities and roads around Gezer – during the Canaanite and Israelite periods – Bible Mapper 3.0

Macalister wrote:

“We have now reached the point where the Biblical history of Gezer begins ; for though flourishing in the patriarchal period, it happens not to be mentioned in the patriarchal record. The first reference to its name in the Hebrew Scriptures is in connection with the Israelite immigration. Taking first the earlier account of this event, preserved for us by the compiler of the Book of the Judges, we read of the failure of the Ephraimites to capture the city, the earlier and the later Semitic populations dwelling together within its walls (Judges 10:29):

And Ephraim drave not out the Canaanites that dwelt in Gezer ; but the Canaanites dwelt in Gezer among them.”

The author of the Book of Joshua, who rarely admits a failure on the part of the Israelites, has quoted the same passage (Joshua, 16:10), but with the characteristic gloss ” the Canaanites dwelt in the midst of Ephraim, unto this day, and became servants to do taskwork “thereby showing that the city was conspicuously a centre of Canaanite population. In the record of Joshua we find a remarkable story of the investment of Lachish by the Israelites, of the coming of the king of Gezer to its aid, and of his defeat and slaughter (Joshua 10:31-33):

“And Joshua passed from Libnah, and all Israel with him, unto Lachish, and encamped against it, and fought against it. . . . Then Horam king of Gezer came up to help Lachish, and Joshua smote him and his people, until he had left him none remaining”.

Several details in this incident deserve notice. In the first place, it is the only case that we find, at any rate in Southern Palestine, of one city aiding another against the invader. It is true that the same chapter relates the story of a temporary coalition between five Canaanite kings ; but it is striking that this is not to make common cause against the common danger, but to punish another of their number who has made a league with the enemy. As in the time of the Tell el-Amarna letters, every town and village community is a unit more or less hostile to all the rest. Indeed such a condition still prevails, to a very large extent. This Ishmael-like state of society makes the action of the king of Gezer yet more noteworthy. Secondly, if it be remarkable that the king of Gezer should offer assistance to any other city, it is still more remarkable that Lachish should be the favored town. Lachish is a good two days’ journey away from Gezer : seeing that there were so many other cities nearer at hand, why did the king of the besieged city send to such a distance for help ? It could hardly be expected in less than five days when we take into account Oriental procrastination.

The excavation itself supplied a hint of a possible answer to this question. During the work of the Palestine Exploration Fund on the Shephelah mounds, it was perplexing to notice that certain types of pottery and other antiquities, common in Tell el-Hesy, failed to appear. They reappeared however at Gezer so conspicuously as to suggest a connexion, possibly tribal, between the inhabitants of the two cities, closer than that which united the folk of either town with those of the Shephelah. One of Abdi-Hiba’s letters, above quoted, seems to present evidence corroborating this deduction. There the names of Lachish and Ashkelon are coupled with that of Gezer, in a way that implies that there was some understanding between them. The third point to consider is the name of the ill-fated king of Gezer. In the Hebrew text this is given as הרם (Horam), in the Greek version AIΛAM or EΛAM. The same form appears in the latter version for the name of the king of Hebron, mentioned in the earlier part of the same chapter ; this appears in the Hebrew as רם (Hoham). Possibly there is some confusion between these very similar names, but without any other source of information it is impossible to detect and to remedy the corruption.

It is most likely that Horam displayed a characteristic Semitic caution when he went to help his ally, and took care to weaken his own town as little as possible. We need not reject the explicit statement that Joshua left to Horam “none remaining”: nothing is more likely than a complete massacre of the officious contingent whose coming added to the difficulty of capturing Lachish. But it is not to be understood that there was a universal slaughter of Gezerices : this is ruled out by both history and archaeology. The city was left with so many defenders that the Ephraimites did not care to risk a siege, and Gezer remained a Canaanite stronghold until the time of Solomon. However, it is enumerated in the list of captured cities in Southern Palestine (Joshua 12:12).

The following verses inform us of the allotment of Gezer (Joshua 16: 1-3):

” And the lot for the children of Joseph went out . . . unto the border of Beth-Horon the nether, even unto Gezer.

(Joshua 21:20-22) :”And the families of the children of Kohath, the Levites, even the rest of the children of Kohath, they had the cities of their lot out of the tribe of Ephraim. And they gave them Shechem . . . and Gezer with her suburbs, etc”.

That is to say, the city was in the border of Ephraimite territory, and whatever Israelite element there may have been in its population belonged to that tribe : also, it was one of the sacred cities of the Pre-Deuteronomic dispensation. When next we meet with Gezer we find that a new element has been introduced into its population; for the Philistines seem to have been dominant over the city in the time of David. Twice in the story of his reign is Gezer referred to, and each time in connexion with that elusive people. The first event is the battle of the plain of Rephaim. The Philistines, alarmed by David’s capture of the Jebusite stronghold and consequent union of the divided monarchy, came up against him : but David “inquired of God ” with the result stated in the following passage (2 Samuel 5: 23-25):

“[God] said : Thou shalt not go up : make a circuit behind them, and come upon them over against the mulberry trees. And it shall be, when thou hearest the sound of marching in the tops of the mulberry trees, that thou Shalt bestir thyself: for then is God gone out before thee to smite the host of the Philistines. And David did so, as God commanded him ; and smote the Philistines from Geba until thou come to Gezer”.

… In the time of David there were Philistines in Gezer, and that at some time he attacked them successfully with the aid of his followers”.

-

The Maccabaean Period

The next chapter relates to the Hellenistic period and the Hasmonean Kingdom which was established by the Maccabees:

“In order to make clear the events in which Gezer figured, and to prevent their being a series of mere disconnected, and therefore unintelligible, incidents, it is necessary briefly to trace the course of the Maccabaean revolt, omitting, of course, everything not essential to our purpose. In 175 B.C. Antiochus Epiphanes began to reign over Syria, and devoted himself to an attempt to force Hellenism, in art and religion, upon the Jews. In 168 B.C. orders were issued for the cessation of Jewish rites, the paganization of the Temple, and the erection of a heathen altar in every village. At Modi’in was an aged priest, Mattathias by name, who had retired thither to escape the persecution. He refused to offer sacrifice on the altar, when commanded to do so, and slew the royal commissioner, as well as a Jew of the village who attempted to conform. This act was the first blow in the great rebellion led by the sons of Mattathias. Mattathias died in the year 166, leaving the leadership to his son Judas Maccabaeus. Judas began by defeating in battle the Syrian generals Apollonius and Seron, the latter at Beth-horon, not far from Gezer. Antiochus, in great anger at these defeats, collected a powerful army ; but lacking money, departed himself to Persia to collect tribute, leaving his kinsman Lysias in charge of the affairs of the kingdom. Lysias set Ptolemy, Nicanor and Gorgias, three favorites of the king, over an army of 40,000 foot and 7,000 horse. These pitched at Emmaus Nicopolis, about five miles from Gezer. Judas, after prayer at the ancient sanctuary of Mizpeh – an interesting touch – marched to Emmaus with the result that (1 Maccabee 4 14:15):

“The Gentiles were discomfited, and fled into the plain. But all the hindmost fell by the sword : and they pursued them unto Gazara, and unto the plains of Idumaea and Azotus and Jamnia.”

During the four following years occurred the battle of Bethzur (the day after that of Emmaus) in which Lysias himself was defeated ; the purification of the Temple and the restoration of its worship ; the defeat of a coalition of the heathen tribes surrounding Judaea ; the battle of Bethzacharias (the first defeat suffered by the Jews) ; and the grant of religious liberty to the Jews, which was forced from Lysias by domestic troubles in Syria. In 162 B.C. the Hellenizers in Judaea, dissatisfied with this defeat of their aims, came with a petition against Judas to Demetrius, who had succeeded to the Syrian throne. They were headed by Alcimus, an aspirant to the high-priesthood. Demetrius was not sorry for an excuse to interfere in Jewish politics, and sent Bacchides, governor of the provinces east of Jordan, to quell Judas and to secure the high-priesthood for Alcimus. In this, Bacchides was unsuccessful. Alcimus again presented his petition and the king sent Nicanor, “one of his honourable princes, a man that hated Israel.” Nicanor visited Jerusalem, blasphemed the Temple, and finally met Judas at Adasa, in the pass of Beth-horon. Here he was defeated and slain, and his army fled (1 Maccabee 7:45):

“And they pursued after them a day’s journey from Adasa until thou comest to Gazara, and they sounded an alarm after them with the solemn trumpets”.

Six weeks afterwards Judas lost his life at the battle of Elasa, in which Bacchides was in command of the Syrians. He was succeeded by his brother Jonathan. Bacchides took advantage of his victory to increase the authority of the Hellenizers, who persecuted the Maccabaean party. Jonathan remained in retirement at Tekoah : his brother John was seized and slain at Medaba : Jonathan crossed the Jordan to avenge his brother, and was intercepted by Bacchides at the fords of the Jordan. The Jews escaped from the trap by swimming the river, but Bacchides retained the upper hand for a time and (1 Maccabee 9:50-52):

“…builded strong cities in Judaea . . . and in them he set a garrison to vex Israel. And he fortified the city Bethsura, and Gazara, and the citadel, and put forces in them, and store of victuals”.

This was in 161. In the following year, 160, Bacchides returned, the death of Alcimus (from a paralytic stroke) removing the reason for his occupation of the country. A period of comparative peace followed.

The strategical importance of Gezer to the combatants on both sides has been well brought out in Professor Clermont-Ganneau’s analysis of this history. Modin, the headquarters of the leader’s family, and consequently the rallying-place of the Jewish side, is easily within sight. The passages that have been quoted seem to shew that the Graeco-Syrians were able to retain possession of this powerful stronghold, and to make use of it as a retreat in case of a check.

In 153 B.C. Alexander Balas (son of Antiochus) seized Ptolemais (Acca) and set up a kingdom rival to that of Demetrius. Demetrius endeavored to secure the powerful aid of Jonathan by making certain concessions, including the releasing of hostages, and the removal of the garrisons placed in the cities fortified by Bacchides (1 Maccabee 10:12-14) :

“And the strangers, that were in . the strongholds which Bacchides had built, fled away ; and each man left his place, and departed into his own land. Only at Bethsura were there left certain of those that had forsaken the law and the commandments : for it was a place of refuge unto them.”.

For the next eight years the history is occupied with the rivalry of these two claimants, ending in 151 with the death of Demetrius, followed in 145 by the death of Alexander. Jonathan had espoused the hitter’s claim, but after Alexander’s death made his peace with Demetrius II, who promised to (1 Maccabee 11:41):

“cast out of Jerusalem them of the citadel, and them that were in the strongholds : for they fought against Israel continuously.”

– showing that the former withdrawal of troops had not been as thorough as the Jews would have desired. This promise Demetrius failed to keep ; Jonathan in consequence once more deserted him, but was ultimately captured and imprisoned at Ptolemais (Acca), where, in 143, he was put to death.

Simon, the last surviving son of Mattathias, succeeded his brother. He had already distinguished himself by his capture of Joppa ; and his defeat at Adida of Tryphon, the former general of Alexander (who had succeeded in establishing Alexander’s son Antiochus on the throne), was all that was necessary to end the war. He then applied himself strenuously to strengthening the -defences of Judaea, and to removing the last traces of the foreign garrisons and of the Jewish Hellenizers. It would seem that the principal of these remained at Gazara ; at any rate the first care of Simon after ” the yoke of the heathen was taken away from Israel” (1 Maccabbee 13:41) was the siege of Gazara, described in the following graphic passage (1 Maccabee 13:43-48):

“In those days he encamped against Gazara and compassed it round about with armies ; and he made an engine of siege, and brought it up to the city, and smote a tower, and took it. And they that were in the engine leaped forth into the city ; and there was a great uproar in the city : and they of the city rent their clothes, and went up on the walls with their wives and children, and cried with a loud voice, making request to Simon to give them his right hand. And they said. Deal not with us according to our wickednesses, but according to thy mercy. And Simon was reconciled unto them, and did not fight against them : and he put them out of the city, and cleansed the houses wherein the idols were, and so entered into it with singing and giving praise. And he put all uncleanness out of it, and placed in it such men as would keep the law, and made it stronger than it was before, and built therein a dwelling-place for himself”.

The remains of the dwelling-place mentioned in the last sentence of this extract, and the inscription by which it was identified, will be described in Chapter III. After this victory Simon went to the citadel of Jerusalem, which he treated in the same way ; and shortly afterwards (1 Maccabee 13:53):

“Simon saw that John his son was a valiant man, and he made him leader of all his forces : and he dwelt in Gazara.”

This capture of the city was duly recorded in the inscription set up at Jerusalem on bronze tablets, in Simon’s honour (1 Maccabee 14 27, 34).

In 139 B.C., four years after Simon’s capture of the city, the new king, Antiochus Sidetes, sent to the high priest his messenger Athenobius to demand the restitution of Gazara, Joppa, and the citadel of Jerusalem, or as an equivalent for the cities and the tribute due from them an indemnity of 1,000 talents of silvera demand that Simon scornfully answered by offering 100 talents.

In 135 Simon, with two of his sons, was treacherously murdered by his son-in-law Ptolemy, who aimed at supremacy. He wished to include John among the victims, and accordingly (1 Maccabee 16 19-22):

“… he sent others to Gazara to make away with John . . . and one ran before to Gazara, and told John that his father and brethren were perished, and he hath sent to slay thee also. And when he heard, he was sore amazed ; and he laid hands on the men that came to destroy him, and slew them ; for he perceived that they were seeking to destroy him”.

John [Hyrcanus] then succeeded to the high-priesthood, with which event the First Book of the Maccabees closes.

The stress laid on the good water-supply of the city will not escape notice. This passage shows that, not long after Simon’s capture of the city, it had again fallen into Syrian hands, though no record has been preserved of the event itself. The destruction of Simon’s dwelling-place, and the erection of an elaborate system of baths over part of the site, may be assigned to the years immediately following this recovery of the city. On epigraphic grounds we may assign to about this period the cutting of the boundary inscriptions marking out the city’s property”.

Courtesy Istanbul Archaeological Museum

(Many of Macalister’s findings are here)

-

The Roman and Later Periods

The report describes the decline of the city, which is typical of Biblical Tels during and after the Hellenistic period:

“Not long after the Maccabaean turmoils the ancient site must have been deserted : this is proved by the total absence of later antiquities. Possibly under the firm hand of the Romans the community, dwindled in numbers owing to the harassing wars of the previous century, felt that they could venture from behind their walls to a more convenient proximity to the springs. Half of the population moved eastward, and settled on the flat land between ‘Ain Yerdeh and ‘Ain et-Tannur, moving later up the hillock which still bears the ruined village of Khurbet Yerdeh. This settlement must have been of some importance, as is shewn by the fine bath and associated drain, described later in this work. The other half went westward and established themselves on the site of the modern village of Abu Shusheh, near the spring known as Bir el-Balad. This village presents few marks of antiquity ; there is, however, a fragment of mosaic pavement in one of the houses.

The tombs opened during the excavation prove that in the fourth century AD there was a considerable Christian community representing the ancient Gezerites. No one lived on the mound itself, but the two sites we have named were both occupied. It was a mixed population, the ancient strain being combined with a foreign element, that now first makes its appearance in the tombs, and with one or two individuals possibly of Negro race. Of the history of the community during this period nothing is known. Very few objects of interest have come down to us from these settlements except those found in the tombs, described in Chap. V. Near Khurbet Yerdeh a ploughman found a fragment of marble, apparently part of a Byzantine tombstone, with a few Greek letters on it”.

-

Ottoman Period

During the late Ottoman period a new village was established near the site, reusing its stones and the water supply:

“Probably during the unsettled conditions of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the village in which the people had established themselves, after the abandonment of the ancient site, became deserted and fell into ruin. It is still remembered in local tradition that the site of the modern village was uninhabited till about a hundred years ago.

For a while the ruined houses were dens of robbers. Then settlers from other villages came, and so the modern population was established. They are a mixed community, the Palestinian tribes of Kais and Yaman being about equally represented, while there is also a fair proportion of Egyptians, settled by Ibrahim Pasha. The first of the new settlers established themselves in caves which still bear their names. This interruption in the continuity of the population is a sufficient reason for the absence of ancient field-names in the neighborhood.

With the new settlers was a certain darwish or holy man, who was known as Abil Shilskek (” father [i.e. possessor] of a top-knot “) on account of his long hair. Nothing but his name and one or two trivial legends are remembered, some of which are recorded in ARP. But when he died his tomb and shrine were erected in the middle of the village, and the old village name of Tell el-Jazar finally gave place to Abu Shusheh. The date in the inscription over the door of the saint’s tomb is 1236 a.i-i., which corresponds to 1820-1 AD. Thus it comes that a squalid village of some 600 souls is all that remains to represent the ancient royal city of Gezer”.

Thus ends the Macalister summary of Gezer’s history.

-

SWP Survey (19th century)

Conder and Kitchener surveyed this area during the Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) in 1873. Their map, part of Sheet 16, shows Tell Jezar (the Arabic name of Tel Gezer) on a hill (marked by the height point 756), near the Arab village of Abu Shusheh. The road from Ramla to Jerusalem, through the Ayalon valley, is seen in the upper right corner, and marked as a dashed line.

Part of map Sheet 16 of Survey of Western Palestine,

by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

Their report of 1874 in Sheet XVI (Volume 2) is one of the most lengthy texts in the PEF report, covering pages 428-440. They regarded Gezer as one of the most important discoveries in Biblical researches, as the city was positively identified by inscriptions found the rocks around the site. The story of the discovery by Clermont-Gannea is detailed in their report:

“‘Whilst running through an old Arab chronicle, by a certain Mudjir-ed-din, M. Clermont-Ganneau quite accidentally came upon the passage which led to this important discovery. The Arab historian relates that about the year 900 of the Hogira an engagement took place between Jamboulat, Emir of Jerusalem, and a party of Bedawi raiders, between the village of Khulda and that of Tell el Gezer. The latter name means literally the hill of Gezer, and the Arab name is exactly the same as the Hebrew one.

As the village of Khulda is still in existence, and, according to the details contained in the account of the Arab author, Tell el Gezer was so near it that the shouts of the combatants were heard at both places, the latter locality should have been easy to fix.

No village, however, of this name was shown on the best maps of Palestine. After having determined theoretically the exact position which the Arab and Jewish Gezer ought to occupy, M. Clermont-Ganneau decided upon making an excursion to test the accuracy of his views on the ground. This expedition, made under adverse circumstances, without escort or tent, and in a desert country wasted by famine, was crowned with success. .At the point which he had previously fixed upon, M. Clermont-Ganneau found the Tell el Gezer of Mudjir-ed-din, and the ruins of a large and ancient city, occupying an extensive plateau on the summit of the Tell. On one side were considerable quarries, from which stone had been taken at various periods for the buildings in the town, as well as wells and the remains of an aqueduct : a little beyond this were a number of tombs hewn out of the rock, the necropolis in which repose the people who have successively inhabited the old Canaanite city. It is scarcely necessary to add that this place is exactly 4 Roman miles from Emmaus-Nicopolis, and that it completely meets all the topographical requirements of the Bible with regard to Gezer.

‘M. Clermont-Ganneau points out the importance of the discovery with reference to the general topography of Palestine. Gezer being one of the most definite points on the boundary of the territory of Ephraim, the current views on the form and extent of that territory, as well as of the neighbouring territories of Judah and Dan, must be very materially modified. This result alone is of importance, and makes the discovery of Gezer an event in Biblical researches”.

- Early excavations (20th Century)

Large scale Excavations of Tel Gezer were conducted in 1902-1905 and 1909-1907 by the PEF, directed by R.A.S. Macalister. The team dug into half of the city, and published a report in 1912. Excavations followed in 1913-1914 and 1923-1924, directed by Raymond-Charles Weill.

In 1934 small scale excavations of the PEF were directed by Alan Rowe (see picture below). New excavations were conducted by the Hebrew Union College of Jerusalem, directed by William G. Dever (1964-1971, 1984, 1990) and by Joe D. Seger (1972-1974), identifying a total of 21 levels spanning the Chalcolithic period to the Roman period.

Alan Rowe’s excavations at Gezer, Oct. 5, 1934

Library of Congress, P/O Matson collection

- New excavations (21st Century)

Renewed excavations (2006-2014, continuing in 2015) were by the Tandy Institute for Archaeology, directed by Steven Ortiz and Samuel Wolff. Additional excavation work is by the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary, who focus on the water system.

-

Modern times

Today Tel Gezer is a National Park, open free to the public. Many families come here at the weekends to enjoy the sights, absorb the history, and picnic.

In July 2022 the park was damaged by a fire.

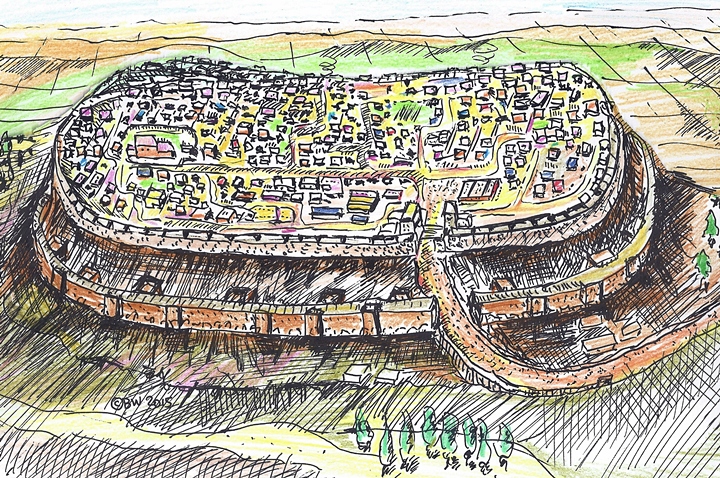

Structure:

The following drawing illustrates how the fortified city would have looked from its south-east side during the Iron Age. The city is protected by two sets of walls, a glacis between them, and towers located along the walls. The entrance to the city is on the south side.

Photos:

(a) Aerial views:

This quadcopter aerial photo shows a view of Tel Gezer from the south. The city extends from the entire length of the photo, with only few sections that are exposed by the excavations.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

Another closer south view is seen in the following aerial photo.

The Macalister report of 1912 described the geography of the site (Vol. 1 p. 1):

“The ruins of the city at present form a mound of accumulation, that attains a height of 756′ [230m] above the sea-level, and about 200-300′ [60-90m] above the level of the surrounding plain. The height is not uniform : at each end, especially the western, it rises in a knoll. These knolls [are] distinguished as the “Western Hill” and ”Eastern Hill” respectively, the saddle between them being called the “Central Valley.” The summit is a long oval area about 1/2 mile in length, and about 450-600′ in breadth. “. The location of the ancient city was chosen because of its location and the water (p.3): “Moreover the neighborhood is blessed, like few other places in South Palestine, with abundant and excellent water”.

The next aerial view viewed the length of the site from the west side, looking towards the east.

(b) Ascent to the City:

The access road from the communal settlement of Karmei Yosef leads to the north western foothills. Some cars also descend up the hill to a small parking lot.

From the parking lot, on the north west side of Tel Gezer, is a great view of the Shephelah – the low lands of Judea.

The National Park constructed an observation terrace that overlooks the excavated area on the southern side of the west hill.

(c) Canaanite City:

During the Middle Bronze II period (2000-1550 BC) the city reached its peak. A 4m thick wall, made of large roughly dressed stones with a mud-brick superstructure, was built around the entire city. The defense system, which include towers and external glacis, was one of the largest system known in the region.

On the foothills of the western hill, as seen in this photo, the archaeologists revealed a section of the city. Their findings included sections of the external walls, a glacis, a Canaanite tower, a city gate, and water system.

- Canaanite Tower

The following photos show the base of the excavated Canaanite watch tower, one of 25 towers that defended the city (as per Dever‘s article). This gigantic tower flanked the west side of the Canaanite gate.

Another view of the tower is below. This massive tower was 16 meters wide and more than 20 meters long!

- Canaanite Gate

The southern gate of the Canaanite city is located near the water works, on the southern slope of the west hill. The gate, dated to the Middle Bronze age, is made of sun dried mud bricks, laid over a stone foundation. It was preserved to a height of 7 meters.

It consisted of three pairs of stone pilasters on which wooden gates were mounted, which is a typical design of Middle Bronze period gates. The pilasters also narrowed the width of the gate, in order to slow down the penetration of the enemy. Wooden doors sealed the gate from the external side.

The gate was flanked on the side by massive bastions – 15.6m (51.2 ft) by 30m (98.4ft).

A section of the Canaanite city wall, connecting the tower to the gate, is seen here from the north side.

These defense systems are one of the largest fortifications of the Canaanite and Israelite periods.

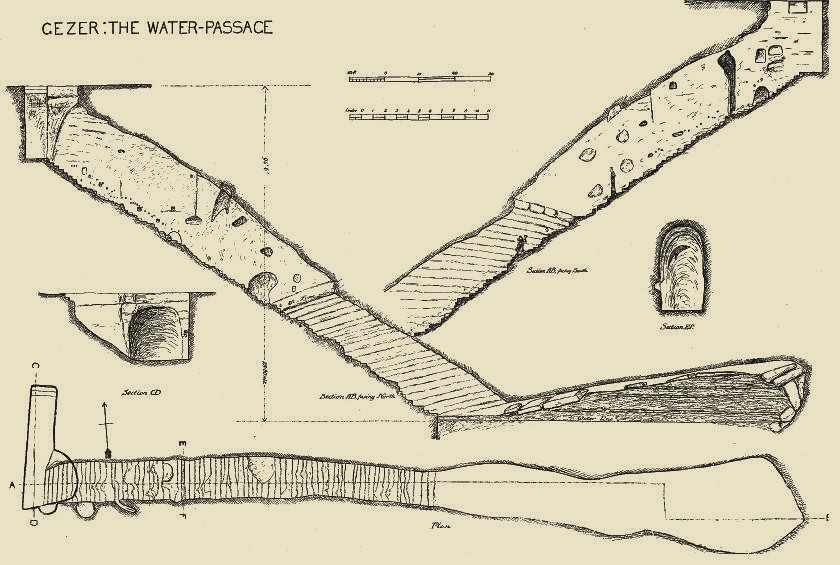

- Water System

North of the city wall and Canaanite gate is a water system, which was a critical element to the defense of the city during siege, and simplified the water supply to the large city.

Its location is indicated as a red marker on the illustration.

Below is a north view of the entrance to the water shaft (on the left), the bridge over a Canaanite tower (on the right), and the Canaanite gate (far left).

A modern stairway leads down to the tunnel. During ancient times the access to the water system was thru a hewn passage, based on a shaft that lead down to a slopped tunnel.

The rock hewn shaft leads down to the entrance of the slopped tunnel, which is seen in the photo below. The 70m-long tunnel leads down to a depth of 40m below the surface, which was the level of the ground water. At the end of the slopped tunnel was a cavern and a basin, where the water was stored. The residents of the city used the shaft and tunnel to fetch water during peace and war times.

The entire tunnel was excavated by Macalister in the early 1900s, but most of the tunnel is blocked due to cave ins. It will be cleaned again and open to its entire depth.

A drawing of the water passage appears in the Macalister report (Volume 3, Plate LII). The top drawings are side sections from both the north and south sides. The lower drawing is a top view along the length of the tunnel (marked as 219ft – 66.75 ft).

The entire tunnel was excavated by Macalister in the early 1900s, but most of the tunnel is blocked due to cave ins. It will be cleaned again and open to its entire depth.

(d) Israelite City:

During the 10th Century BC the city was reinforced with a new set of inner and outer walls that encompassed the entire mound. Additionally, a new 6-chambered gate was added on the south side.

The location of the south walls, at the area west of the gate area, is indicated as a red marker on the illustration.

A view of the excavated area along the south walls is seen in this aerial view, captured from the south. The gate is on the right side, and the walls extend to both directions, although only the left side is visible.

![]() A flight over the site can be seen in this drone video:

A flight over the site can be seen in this drone video:

- Inner wall

The Israelite inner wall was of a casemate form (Hebrew: “Sogarim”), based on two parallel walls (one external and one internal), which are connected at small intervals with inner walls, thus creating chambers. Each chamber is 5 by 1.5m (16.4ft by 4.9ft), separated by 1.5m (4.9ft) thick walls . This wall can be seen in this view stretching along the foothill, from the gate (seen on the left) towards the center background.

The casemate double-wall is a common design of many 10th Century BC Israelite cities, although it first appeared in Canaanite cities at the 17th Century BC (as found in Ta’anach, Shechem and Hazor).

- Glacis

On the outer side of the Iron Age wall was a stone glacis, going 9m (29.5ft) down the slope of the hill, at about 15 degrees angle.

- Outer wall

A 1.5m (4.9ft) thick outer wall was constructed during the Iron Age all around the city. Towers and bastions were added along the wall.

Standing over the excavated area, Uncle Ronnie overlooks the excavation area.

- Solomon’s Gate

The southern gate of the Israelite city is one of the important findings on the south side of the mound.

The location of the gate is indicated as a red marker on the illustration.

The inner gate complex was found in the Macalister excavation of the early 20th Century. It is composed of a central passage, and 6 chambers – three on each side. The gate, oriented to the south, was built of large hewn limestone boulders, with two towers on its external side.

This gate design is typical to the Iron Age II, and is commonly attributed to King Solomon. It follows the same types of gates as found in other Israelite period cities –Megiddo and Hazor. These findings match the Bible’s accords of Solomon projects (1 Kings 9:15): “And this is the reason of the levy which king Solomon raised; for to build the house of the LORD, and his own house, and Millo, and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer”.

A water drainage channel, covered with large slabs, passed under the passage way in order to drain the runoff water out of the city, similar to Lachish and BeerSheba.

An eastern view of the gate area is seen in the following photo. The 6 chambers, three on each side, are seen in the center of this photo.

Each chamber contained plastered benches, and one of the chambers had a large water basin (seen below, on the bottom left side). During peace times the chambers functioned as a meeting place, as the elders of the city convened here for deciding on matters of the city and for judgments, as described in the Bible (e.g., Deuteronomy 21:19): “…and bring him out unto the elders of his city, and unto the gate of his place”.

The chambers could also function as storage areas, and during war times were used for military purposes.

- Four Room House

West of the gate area is a new excavation area, which was exposed in the 2006-2009 seasons. Here an Iron-Age four-room house was unearthed. This building consists of three long rooms oriented east-west, and a broad room to the west. This building is larger than typical rooms of this type, with an estimated area of 135 square meter.

The rooms are separated by large limestone pillars, each 1m high and 0.5m square. Here are two of the pillars, and behind them a cobble surface of one of the two southern rooms, with a wall behind it.

The building was dated, according to the ceramics found inside it, to the 8th Century BC. Its destruction was attributed to the Tiglath-Pileser III conquest (732 BC).

- High place – Monolith temple

An Israelite period shrine, including 10 monoliths and a stone basin, is located on the north-east side of Tel Gezer.

The monoliths are of different sizes and shapes. They may have symbolized the city states or the tribes, and serve as a place where alliances are created or renewed.

The stone basin may have been as a container for the ceremonial blood libation (ritual pouring of liquid as an offering to God).

An example of such ceremony was performed by Moses (Exodus 24 :4-6): “And Moses wrote all the words of the LORD, and rose up early in the morning, and builded an altar under the hill, and twelve pillars, according to the twelve tribes of Israel. And he sent young men of the children of Israel, which offered burnt offerings, and sacrificed peace offerings of oxen unto the LORD. And Moses took half of the blood, and put it in basins; and half of the blood he sprinkled on the altar”.

(e) Sheikh’s tomb:

Ruins of a Sheikh’s tomb structure are located in the north west side of the mound. Steps lead up to a raised platform, which serves as an observation point.

The tomb is dated to the 16th Century. It may have been of Sheikh Mohammed al Jazarli, whose name preserves the identity of Gezer.

Special findings:

The excavations unearthed thousands of findings. Noteworthy are two – the Gezer tablet and the Gezer boundary rocks.

(a) Gezer Tablet:

The limestone tablet, written in the ancient Hebrew script, is on display in the Archaeological museum in Istanbul. It was discovered in Gezer, and is known as one of the earliest Hebrew texts. The tablet is dated to the 10th Century BC (King Solomon period), and tells the agricultural phases of the year in puzzles using a poetic language in 7 lines:

- “Two months, late crops” [September-October] – “Two months

- sowing” [January-February] – “Two months, spring crops” [November-December]

- “One month, cutting flax” [March]

- “One month, harvest if barley” [April]

- “One month, all the harvest” [August]

- “Two months, fruit vines” [May-June]

- “One month, summer fruits” [July]

Photo courtesy of the Archaeological museum in Istanbul

(b) Gezer Boundary Inscriptions:

Around Tel Gezer are 1st Century BC Bilingual inscriptions, bearing two lines : “Alkios” in Greek, and Hebrew letters with the name “Boundary of Gezer”. These stones provided a positive identification of Tel Gezer, but their function is debated among scholars – are they markers of the city limits, and for what purpose, or perhaps they are Sabbath stones marking the edge of the allowed travel of Jews during Sabbath or Holidays.

![]() Read more on the Gezer Boundary inscriptions.

Read more on the Gezer Boundary inscriptions.

Misc:

This scene of the herd of goats, on top of Tel Gezer, is like nothing changed in the past thousands of years.

The goats mow the dry grass that grew over the winter… The cattle egret birds follow the herd to collect insects and vertebrate prey that are disturbed by the animals.

A closer view of the hungry goat:

Etymology (behind the name):

* Names of the site:

- Gezer – Biblical name of the city. Perhaps based on the root “g.z.r” – cut. So the site can mean “cut off”.

- Tell Jezar – Arabic name, based on the Hebrew name.

- Gazara – city name during the Hellenistic period

* Names of nearby points of interest:

- Kibbutz Gezer – communal settlement, named after ancient Gezer; established 1945

- Karmei Yosef: The vineyards of Joseph; communal settlement est. 1984, named after Yosef Sapir, a late politician

- Abu Shusheh – ruins of an Arab village (established at the end of the 18th Century; its lands were purchased in 1882); The name means (as per PEF): ‘father of, ‘wearing ‘a top knot.’, on account of the long hair of the Holy Man in the village.

- Kh. Yerdeh, ‘Ain Yerdeh – Arab name of ruins/springs near Tel Gezer; Yerdeh is based on the Hebrew/Arab root word y.r.d – going down (to fetch water)

Links and References:

* Archaeology and History:

- Tel Gezer Project

- Tel Gezer report – S. Ortiz, S. Wolff, G. Arbino [Hadashot Arkheologiyot Volume 123 Year 2011]

- The excavation of Gezer 1902-1905 1907-1909 Macalister’s report of 1912, Volume 1 (pdf; 452 pages) – recommended resource

- Fire damaged Tel Gezer – Jpost July 2022

- Late Bronze Age and Solomonic Defenses at Gezer: New Evidence – William G. Dever [1986] – thanks to Merry Beth

Additional reports: Volume 2 Volume 3

- Library of Congress – old photos of Gezer

* YouTube:

- Excavating Tel Gezer (2014, SAGU, 52:01 minutes)

- Gezer, a Biblical city (2014, SBA, 4:10 minutes)

- Flight over Tel Gezer (2015, Biblewalks, 2:21 minutes)

* Other sites:

- Gezer Boundary Rocks 13 inscriptions found around Gezer

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

- Biblical Water works – other sites with impressive water systems

BibleWalks.com – touring the Land with the Bible in hand

Ramla Khan <<–previous site—<<< All Sites>>>—next Shefela site—>>> Gezer Boundary Rocks

This page was last updated on May 27, 2024 (increase size of photo, remove pano)

Sponsored links: