Multi-period sites of Qa’un, on the side of a major trade route.

Home > Sites > Samaria > Qa’un sites

Contents:

Overview

Aerial Map

History

Photos

*Khirbet Qaun

– Eastern Section

– Western Section

– Aerial Video

*Tel Qaun

*Qaun Cemetery

Etymology

Links

Overview:

Khirbet Qa’un (Ka’aun) is a large ruin located on a ridge along the south bank of Nahal Qa’un, on the south western edge of the Beit Shean valley. Covering 90 dunams with dozens of ruined structures, the village was populated during the Late Roman and Byzantine period. Its ruins were reused in later periods.

In the vicinity of the Byzantine village is a cluster of 6 other sites of various periods, starting from the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze age. This large concentration of sites centering in a small area were due to the year long water supply of the Qu’an spring, the major route that passed here, and the fertile farming areas around the sites.

Map / Aerial View:

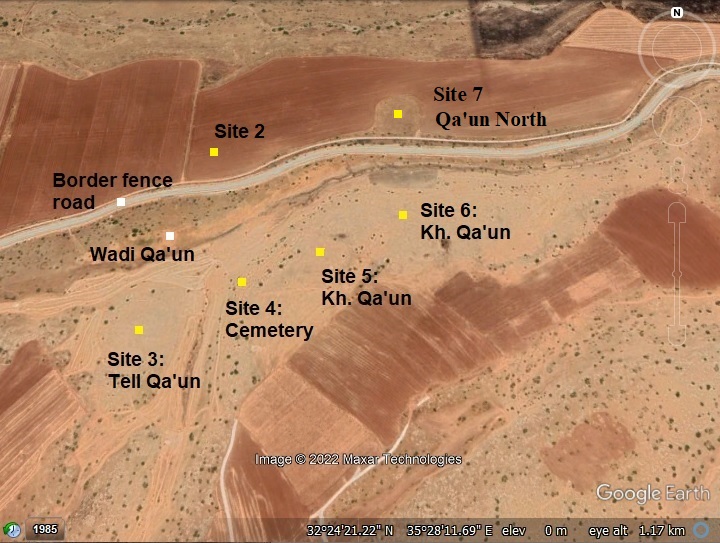

An aerial map is shown here, indicating the major points of interest around the sites of Qa’un south of wadi Qa’un (marked by yellow squares). The sites are numbered 3-6, based on the Manasseh Hill Country survey. The Roman/Byzantine period village, later occupied in middle ages periods, is Site #6 – Kh. Qa’un. It is the largest site, covering an area of 90 dunams (22 acres). Site #3 is a Bronze period city, site #5 is of Intermediate Bronze age, and a large cemetery is in site #4. Across the border fence, north of the valley, is Site #2 of the Early Bronze period. A new site #7 was discovered in 2026 with remains of the Bronze and Iron Age.

History:

Overview

- Chalcolithic

Settlement in the Qa’un area started from the Chalcolithic period on Tell Qa’un. The hill (Manasseh Hill Country survey’s site #3) was occupied on the west side of the spring, on the side of the ancient trade route. The fertile area around the site, and the water supply from the spring, provided farming capabilities.

- Bronze/Iron Age period

Tell Qa’un (Site #3) continued to be settled during the Bronze period.

Ceramics collected on the mound and on its foothills were dated by the Manasseh Hill Country survey (Vol 4, Site 3, p.114) to the following periods: Chalcolithic period (5%), Early Bronze 1 (15%), Early Bronze 2 (20%), Intermediate Bronze (10%), Mid Bronze IIb (15%), Late Bronze (2%), Iron I (10%), Iron II (10%), Persian (10%), Hellenistic (3%).

During the thousands of years of occupation, a large cemetery (with 200 burial caves) was built into the hillside east of the site. In this ancient cemetery, reviewed by the survey team as Site 4, the following remains were dated: Chalcolithic period (3%), Early Bronze 1 (12%, Eraly Bronze 2 (28%), Intermediate Bronze (22%), Mid Bronze IIb (15%), Iron I (8%), Iron II (2%), Persian (7%).

There are other Bronze period sites in the near vicinity, north of Wadi Qa’un and the border fence –

- Wadi Qa’un (1) (Site #1 in the MHC survey) – Remains on the north bank of Wadi Qa’un, 1 km west of Qa’un spring, 3.5 dunams, Intermediate Bronze period (100%).

- Kh. Qaun (1) (Site #2 in the MHC survey) – A low mound north of Tel Qa’un, on the north bank of Wadi Qa’un, 6.5 dunams, Early Bronze Period (100%)

- Wadi Qa’un (2) (Site #7 in the MHC survey) – a stretch of ruins along the north bank of Wadi Qa’un, probably an extension of the Intermediate Bronze period settlement (Wadi Qa’un (1))

Another Bronze/Iron age settlement (Site #7) was discovered by the Jordan Valley Archaeological Survey in 2026 on the north bank of Nahal Qa’un. According to member Ayelet Keidar, this could have been an Iron Age fortification along the ancient road, as seen in other Iron Age fortified stations in the Northern side of the Jordan valley. It is marked on the 1940s map as “cemetery”.

- Biblical map

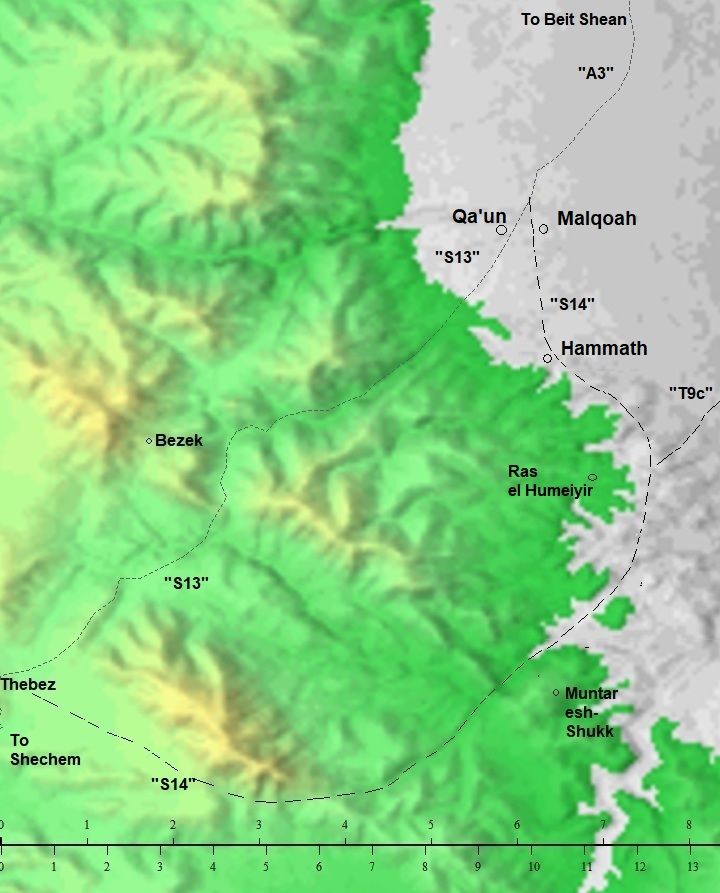

The cities and roads during the Canaanite and Israelite periods are indicated on the Biblical Map below. The map shows the 2 routes from Samaria to Tel Rechov (Rehob) and Beit Shean (most important sites in this region) and to TransJordan Mountains via the fords along the Jordan river near Tell es-Sakut.

The sites were surveyed by the Manasseh Hill Country survey (Volume 4 sites 1-7).

Map of the area around Qa’un- during the Canaanite and Israelite periods (based on Bible Mapper 3.0)

David Dorsey (“The Roads and Highways of Ancient Israel”, 2018) shows a detailed map of the roads around the site during the Bronze/Iron age. The main road from Rechov/Rehob southwards is marked as A3. It passes near Tel Malqoah, 3km north of Hammath, where the road splits to two routes towards Shechem and Samaria:

- route S13 – The northern route, via Qa’un, along Wadi el Khashneh, to Aser (modern Tayasir) and Thebez (Tubas). A Roman road also used this route, as indicated by milestones found along the route.

- route S14 – The southern route: After passing Hammath, it continued south along the foothills to Ras el-Humeiyier. It then turned south west thru the valley of esh-Shukk, where a pair of Iron Age fortresses guarded the road, and continued west along Wadi Malikh to join route S13 at Aser (Tayasir) and Thebez (Tubas).

Another route, that is not defined in Dorsey’s book, could have entered Nahal Bezeq via the north bank of Qa’un.

Biblical identification:

The Biblical identification of Tell Qa’un is not certain. Zertal provides a number of suggested identifications for the Biblical city (MHC survey, Volume 4, p. 96):

- Yokmeam (1 Kings 4:10): “And Solomon had twelve officers over all Israel..from Bethshean to Abelmeholah, even unto the place that is beyond Jokmeam:” Zertal brought arguments against and in favor this suggestion.

- Ataroth (Joshua 16:7): “And the border of the children of Ephraim…And it went down from Janohah to Ataroth, and to Naarath, and came to Jericho, and went out at Jordan”. Zertal also argued against it, and suggests it was in Khirbet ‘Aujah el-Foqa near Jericho.

- Abel Meholah (several Biblical verses) – see Abu Sus and Sakut

- Late Roman/Byzantine period

After a drop of settlement activities during the Assyrian, Persian, Hellenistic and Roman periods, during the Byzantine period the region Beit Shean and Jordan River witnessed a surge in settlement and trade.

During this period a new settlement (Khirbet Qa’un (3), Site #6 in the MHC survey) was built east of the ancient Bronze/Iron Age sites. It spread over two ridges south of Wadi Qa’un and near the trade route that passed along the south bank. The settlement grew to a large (90 dunam) site.

The survey dated the ceramics as Late Roman (17%), Byzantine (45%), Early Muslim (10%), Ottoman (18%) and Modern (10%).

The Byzantine settlement was probably destroyed during or a short period after the Muslim conquest of the land. Mud houses were built over the Byzantine ruins during the Ottoman and modern period. In 1967, following the Israeli conquest, its residents relocated to nearby village Bardeleh. Since then the site is in ruins.

- Ottoman Period – (1516-1918 A.D.)

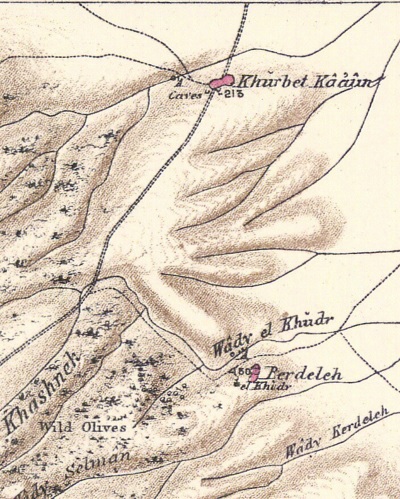

The area was examined in the Palestine Exploration Foundation (PEF) survey (1866-1877) by Wilson, Conder and Kitchener. They wrote about the site (Volume 2, Sheet XII, p. 238):

“Khurbet Kaaun —There are caves, and the place appears to have been an ancient site, perhaps Cola. (Judith XV. 4.)”

And also on page 227 the surveyors provided additional description of the mud-brick Ottoman village, but misidentified the site with Kaina – one of the stations of the Egypitans’ advance to conquer Megiddo during the 15th century BC:

“Khurbet Kaaun is a place of the same character, with mud hovels among ruins, and caves also inhabited. The place has the appearance of an ancient site and a fine spring. It may perhaps be the site called Kaina in the inscription of Thothmes III, which was a place with water and south of Megiddo, occupied by the southern wing of Thothmes’ army advancing from Aaruna (perhaps ‘Arraneh, Sheet IX.). These two identifications agree with the supposition that the Megiddo of this inscription is Khurbet Mujedda”.

This map is part of sheets 12 of their survey results, with Khirbet Ka’aun in the path of the ancient route from Samaria (exiting from Wadi Khashneh) to the Jordan valley. The caves marked east of the site are a large cluster of burial caves.

Part of map sheet 12 of Survey of Western Palestine, by Conder and Kitchener, 1872-1877.

(Published 1880, reprinted by LifeintheHolyLand.com)

- British Mandate

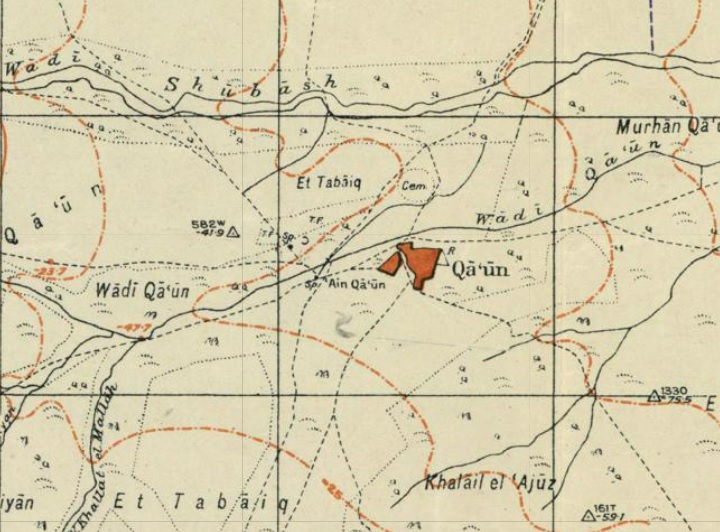

A 1940s British map shows the area around the site with more details.

The spring (Ain Qa’un) is shown to the west of the Ottoman period village, on the south bank of Wadi Qa’un.

British survey map 1942-1948 – https://palopenmaps.org topo maps

License: public domain under the UK Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998

- Modern period

During the independence war, a force of the Arab liberation army, led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji, amassed 600 soldiers in Qa’un. In March 1948 a Palmach unit conquered the village and blew up 15 houses. After the war, its residents returned back to Qa’un. In 1967 the village was incorporated into Israel. The village was abandoned, and its residents moved to nearby village of Bardele.

The sites were surveyed by the Har Menasseh Country survey by Adam Zertal (volume 4, sites #1-7).

Photos:

(a) Khirbet Qa’un – Late Roman/Byzantine settlement

The largest site in the complex of 7 sites on both sides of Wadi Qa’un is Khirbet Qa’un(3), which was settled in the Late Roman period and reached a peak during the Byzantine period.

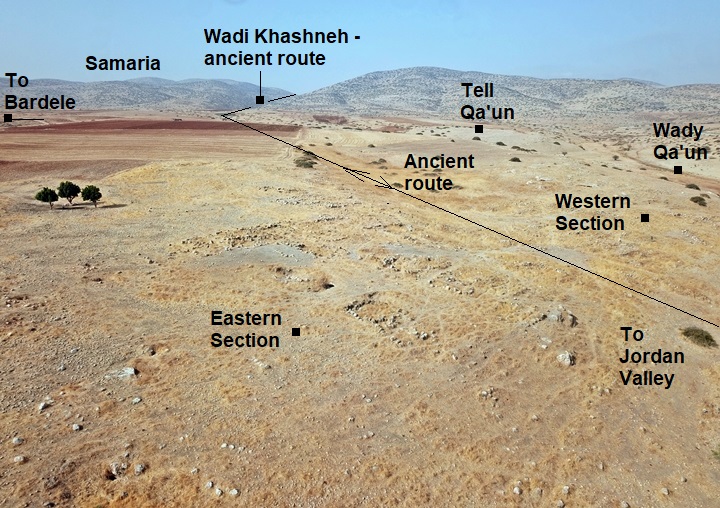

The following aerial view shows the site from the east side looking towards the west with the Samarian hills in the background. The ruins are spread over 90 dunams, on top of two ridges that descend to the south bank of Wadi Qa’un.

Click on the photos to view in higher resolution…

Khirbet Qa’un has 2 sections that are separated by a low valley – an eastern and a western section. This is indicated on the following illustration, with the 2 main parts of Khirbet Qa’un.

The ancient route from Samaria passed along Wadi Khashneh, via Qa’un, along Wadi Qa’un, descending towards the Jordan valley.

Each of the sections are detailed below.

(a1) Eastern section

The eastern section of Khirbet Qa’un is located on a ridge bounded by two low valleys. This aerial view shows the entire area of this section and the traces of ruins that are visible.

On the eastern side of this section are remains of a large 40x40m structure.

A ground view of this structure is shown below. On its south side are 3 rooms.

To the west of the large structure are additional traces of ruins.

In the view below are the scattered ruins, and Wadi Qa’un below the foothills. On the north bank is the security fence and the security road.

Another ruined structure:

On the south side of the large structure are additional courtyards that are bounded by straight lines. Notice the long walls to the left of the triple trees. These courtyards are also located on the south western areas.

Also, farther on the south-east side, are many Byzantine period burial caves that are built along the ridge.

Below is an aerial view of the south east side, with a view towards the south:

Uncle Ronnie and archaeologist Ayelet Keidar examine bases of the walls on the southern side:

On the western side of the eastern section is another group of about 30 more structures.

Yet another structure is in the next photo. These ruins were remains of the Roman/Byzantine period, and were reused during the Middle Ages and Ottoman period.

(a2) Western section

The western section of Khirbet Qa’un occupies a ridge that is separated from the eastern section by a low valley.

On the western section are 20-30 additional structures. Most of the structures have a underground cave that was used a a cellar.

The western section was the center of the Arab village.

The following view is from the western section looking towards the eastern side.

(a3) Aerial Video

![]() Fly above and around Khirbet Qa’un with this YouTube video.

Fly above and around Khirbet Qa’un with this YouTube video.

Video and photos captured on Sep 2022

(b) Tell Qa’un – Site #3

Tell Qa’un, site #3 in the MHC survey, is located 400m west of Khirbet Qa’un, closer to the Qa’un springs. This multi-period Bronze/Iron period mound is located on a ridge overlooking Wadi Qa’un, near the Qa’un springs. Its area is 7 dunams.

The site has been severely damaged by farming.

Few structure remains are seen on this low hill.

A peripheral wall may have been constructed around the site. Only few sections of the wall were found.

Evidence of illicit digging can be seen on the hill.

Ceramics collected on the mound and on its foothills were dated by the Manasseh Hill Country survey (Vol 4, Site 3, p.114) to the following periods: Chalcolithic period (5%), Early Bronze 1 (15%), Early Bronze 2 (20%), Intermediate Bronze (10%), Mid Bronze IIb (15%), Late Bronze (2%), Iron I (10%), Iron II (10%), Persian (10%), Hellenistic (3%).

We examined some of the ceramics found on the mound.

1: A Persian period vessel

2: The bottom of a Mortarium (pottery Kitchen vessel), probably Persian period.

(c) Qa’un cemetery – Site #4

During the long years of occupation, a large cemetery (with 200 burial caves) was built into the hillside east of the site. In this ancient cemetery, reviewed by the survey team as Site #4, the primary remains were dated to the Bronze age.

This photo of the area was captured across the border fence. Notice the hundreds of pot holes.

Etymology – behind the name:

* Names of the site:

- Qa’un – name of the sites and the valley; unknown meaning.

- Wady Qa’un – a stream that feeds from Qa’un spring near Tel Qa’un;

- Wady Shubash – A 25km long stream, runs in parallel and adjacent to Wadi Qa’un; Arabic meaning (PEF): the agent of real-estate; Hebrew name: Nahal Bezeq

- Wady el Maleh – Arabic: the salt valley (named after the hot springs)

- Wady el Khashneh – through this valley was an ancient route to Qa’un; Arabic: “the rough valley”

Links:

* External links and references:

- “The Manasseh hill country survey” Volume 4 pp. 109-126 [Adam Zertal, 2005, Hebrew]

- Site 2: Khirbet Qa’un (1), Early Bronze 1, 6.5 dunums

- Site 3: Tell Qa’un, Bronze/Iron ages, 7 dunams

- Site 4: Qa’un cemetery, primarily Bronze Age, 10 dumans

- Site 5: Khirbet Qa’un (2), Intermediate Bronze age, 60 dunams

- Site 6: Khirbet Qa’un (3), Roman/Byzantine/Muslim/Ottoman, 90 dunams

- “The Roads and highways of ancient Israel” (Dorsey, 1991) – The Bronze and Iron age road is numbered #S14 (p. 173)

* Internal Links:

- Drone Aerial views – collection of Biblical sites from the air

BibleWalks.com – “Arise, walk through the land in the length of it and in the breadth of it…”

Esh-Shaak <<<—previous site—<<<All Sites>>>— next site—>>> el Janab cave

This page was last updated on Jan 17, 2026 (add site 7)

Sponsored Links: